How to fix the BBC

In Beeb We Trust

Last week, I made the case that the BBC faces an existential threat: The end of its universal role. Structural changes in the economics of making and delivering content means that the licence fee will be be abolished, and Auntie will face oblivion.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Last time I promised — unwisely — that this week I would offer the solution and make a radical proposal for how to fix the BBC. Scarily, lots of you signed up to find out. So, here’s a broad outline of what I’m thinking.

This is part of a series on the BBC. Read part one here first if you like, or just uncritically accept my premise stated above and read on. Either way, you should sign up (for free) to get more of This Sort Of Thing1 in your inbox, covering a wide range of topics.

The Big British Castle’s Moat

The first step towards a strategy is identifying a “moat” — the place where an organisation has the most entrenched competitive advantage.

This is what Disney did a decade ago when it underwent its own radical transformation. Then CEO Bob Iger realised Disney’s moat was not the parks or the TV networks, but the characters it owned, so the company doubled down and bought Pixar, LucasFilm (Star Wars), Marvel and, most recently, 20th Century Fox2.

This means that even if Warner, Paramount or Viacom could build a streaming service as technically capable as Disney’s, they will still never have Star Wars. Or Avengers. Or The Lion King. And so on.

What makes Disney’s unrivalled IP3 such a powerful moat is that no off-brand sci-fi property will ever be able to match the rose-tinted memories you have of watching A New Hope for the first time aged seven with your dad4.

So, what is the BBC’s moat? As popular as Doctor Who and Top Gear are, it isn’t IP — and since we evolved beyond TV remote controls where 40% of the buttons led to the BBC, it isn’t control over distribution either. In a world of streamers, it is no longer the ability to do things at scale.

That’s why, in my view, the moat is something that is less tangible: Trust.

In Beeb We Trust

It’s hard to believe if you’ve ever spent any time on Twitter, but broadly, people trust the BBC.

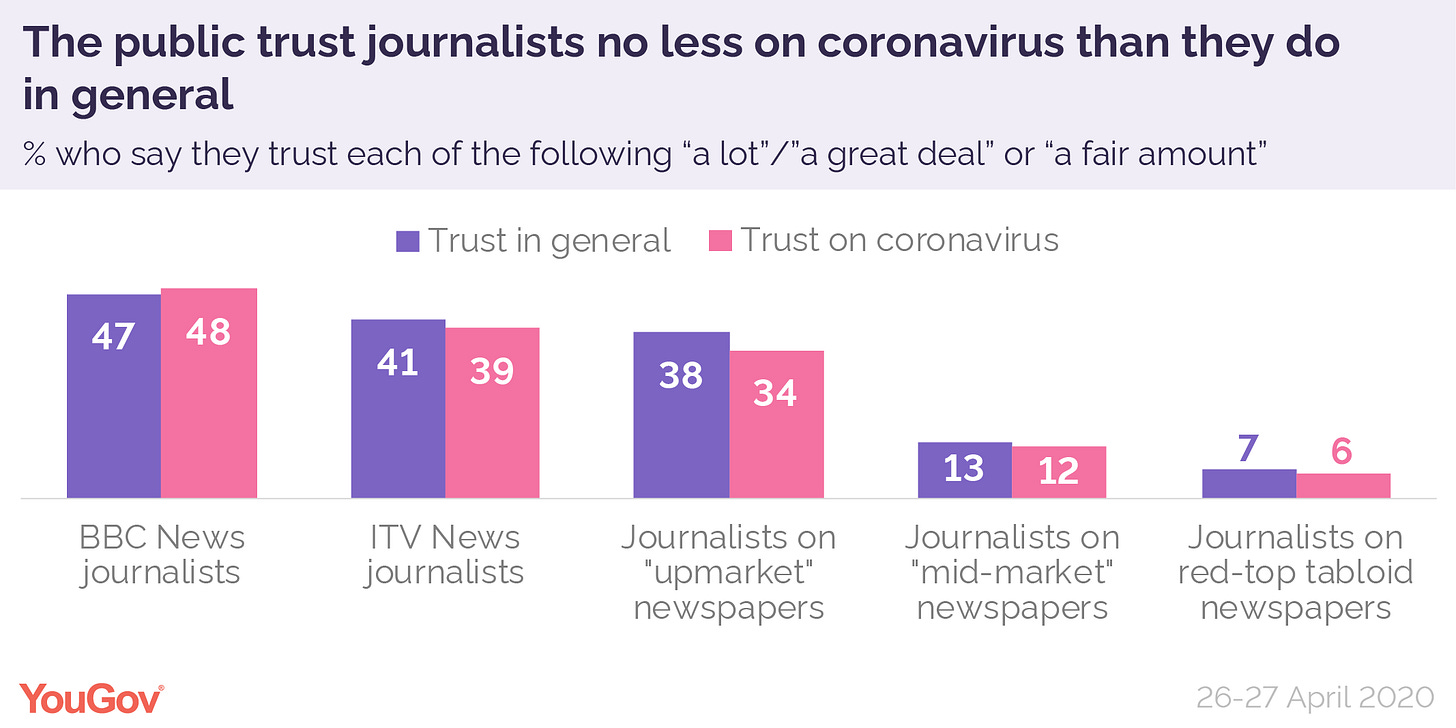

There’s polling to back this up. Look at this chart from YouGov, which shows the BBC is the most trusted news source in Britain — at least compared to ITV News, and newspaper journalists of all stripes.

I’m sure if I looked harder, I could find historical data showing that trust in the BBC has collapsed over the last several decades, just as trust has collapsed in every other institution. But the fact is that trust in the BBC remains relatively high5.

In my view, the touchstone for the BBC of the future shouldn’t be about how it broadcasts, or what it broadcasts, but about reaching audiences with trustworthy information.

Why trust? It is self-evident to say, but trusted institutions that provide trustworthy information are good things to have in society. Everyone knows this, and yet trust is a big contemporary problem in our more chaotic information environment. Hence worries about fake news, conspiracy theories, scams and people retweeting any old shite because it supports their ideological priors6.

In terms of the BBC’s public service remit, to make the BBC’s purpose building and maintaining trust is obviously a slam-dunk. It’s a role the BBC was literally created to play.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not using “trust” to paraphrase the BBC’s Reithian mission to “inform, educate and entertain”. To focus on trust is to laser target its mission even more tightly, and it should drive every decision made by the corporation.

The path of least resistance

Now we have our mission, but how can the BBC deliver it? First, it needs to dramatically transform its role in the media ecosystem.

Imagine a BBC that stays as it is now. Let’s call this an imperial BBC. What happens when you wind the clock forward 10, 20, or maybe even 30 years?

One thing we can be certain of is that in the future, BBC content will not appear by default when you switch on the TV. Instead, BBC content will be mediated through an application layer on whatever device the viewer is using. To end users, the BBC will be an icon on a home screen, competing for attention against the rest of our digital lives.

Perhaps future technology will be smarter, offering the BBC’s catalogue of programmes and services through an algorithmic interface, intermingled with content from other providers. A bit like, for example, Apple’s TV app does now.

In any case, it means the BBC will lose the control it has enjoyed for the last 85 years and the challenge I identified last week — of universality, or lack thereof — would persist. It would tumble into the death spiral.

Funding an imperial BBC would be impossible. Assuming the licence fee is killed by a Tory government of the not too-distant future, an imperial BBC would need to switch to something like a subscription model, becoming just another competitor in an already crowded space.

According to Kantar, the average UK home currently subscribes to 2.3 streaming services7. At a certain point, a ceiling will be hit on how many of those people are willing to subscribe to. But even if it is, on paper, successful, the number of subscribers would obviously be much lower than the 100% of people compelled to pay the licence fee. The BBC’s income would fall, making competing on an imperial scale even harder8.

But the biggest problem for an imperial BBC is the issue of scale. I touched upon this last week. A recent trend in streaming video — and the reason the big players are so dominant — is that they (ironically) have scaled to achieve a universality of their own. There’s something for everyone on Netflix and Amazon. Even Disney has diversified, launching a library of adult-oriented content under its “Star” brand.

An imperial BBC would be like an EFL Championship team competing in a league made up of deep-pocketed UEFA Champion’s League winners. This is why the BBC needs to play a different game.

The broadband levy dead-end

A brief point on an alternative to subscription that has been proposed by the BBC itself. It pitched a “broadband levy” — essentially a tax on top of a broadband internet connection.

However, this is not the saviour of an imperial BBC. For a start, it would have to be created against a backdrop of whichever party is in not in power banging the drum about the government wanting to slap £13 a month extra on top of your broadband bill. Secondly, it would face exactly the same problem of universality the BBC faces now. So the political coalition to keep it in place would be extremely tenuous, especially if the corporation is as handsomely funded as currently9.

So a broadband levy doesn’t solve anything — it just recreates the same time bomb the licence fee has.

The great unbundling

So, what’s the alternative to an imperial BBC? How can the corporation of the future deliver on its new mission of being the trusted voice in a crowded room?

Perhaps the BBC’s best option is to make a strategic retreat from broadcasting.

That’s not as insane as it sounds. I very specifically mean broadcasting and not content.

It’s time to unbundle the BBC.

We know that streamers are going to win on distribution10. Instead, the BBC should inject its public service output further down what tech people would refer to as the “stack”.

Instead of competing for attention with Netflix, YouTube and Fortnite, it could switch to producing content for Netflix, YouTube and Fortnite.

The BBC of the future should not create trusted content, with trusted information, only to limit it to viewers on its own distribution channels. It should work with whatever partners are necessary to get reliable, trustworthy information out to the widest possible audience.

This means that the BBC can continue to produce news, documentaries and even scripted content for Netflix, Amazon, and so on, but it would also completely free the BBC in terms of format to better serve audiences.

For example, as Rob Manuel argued a few years ago in Prospect, the BBC should make its own gaming content on Twitch and YouTube, to provide a kid-friendly alternative to a wholly unregulated space.

The next time there’s a pandemic, the BBC can deploy its full resources to help credible scientists and doctors produce wide-reaching TikToks and YouTube videos, with those platforms as the focus rather than as a secondary hosting platform for clips from TV11.

There are already examples of this. For instance, the BBC currently funds 165 “local democracy” reporters around the country. These are journalists trained and paid for by the BBC who work for privately owned local newspapers and other news outlets to report on all of the worthy public service stuff that is no longer profitable because of the internet, such as boring council meetings.

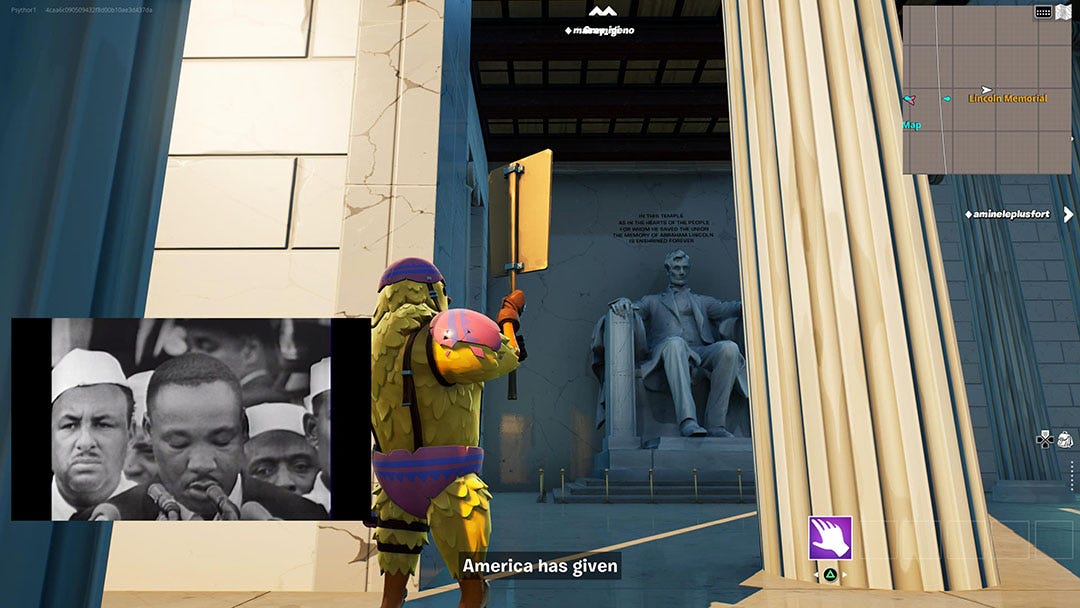

Outside of the BBC, other media brands are experimenting with reaching audiences through new formats. For the anniversary of the March on Washington, TIME magazine partnered with Fortnite to produce an interactive game mode where your character (in my case, an anthropomorphic chicken) could wander around the Lincoln Memorial while listening to the famous speech. I don’t know if this specific idea was the best idea (I mean, look at it), but it definitely reached more people than a standard magazine feature.

Following this model, the BBC should use its trusted brand to inject trustworthy content into our information diets, and use its resources to strengthen democracy in the new spaces where democracy takes place.

What about the BBC functions that don’t currently work towards this explicit goal? This is why unbundling makes sense. To be clear, I very much do not mean privatised. But there’s no super-specific reason why everything it does has to exist under one roof, with one management structure, and one massive target on its back for the Daily Mail to take convenient aim at.

Take talent nurturing. We could have a separate publicly funded agency with its own budget to co-fund productions that take risks, or feature a more diverse cast and production team.

Then when a new piece of content is created, its funding can be sought from relevant agencies - just like how if you visit a theatre today, you might see that it gets some of its cash from the Arts Council, and another tranche of cash from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

The end result of this would be an ecosystem of public institutions that together add up to do what the BBC of today does, but with the flexibility to work towards their diverse goals, without being weighed down by the rest of the corporate structure12.

Trade-Offs

Obviously there would be trade-offs with my dramatic ‘retreat from broadcasting’ pitch. To sketch out a little more how I’d envisage it working, I’d retain the iPlayer as a “backstop” for people who don’t subscribe to any streaming services, and as a single point of collecting all of the non-commercial BBC-branded content in one place. But iPlayer wouldn’t be the focal point, nor the place where viewers have to go to consume BBC content. From the BBC’s perspective, it shouldn’t really matter whether people are watching public service content on YouTube, Netflix, iPlayer or even BitTorrent.

I’d also use the regulatory power of Ofcom to insist that streaming services carry the public service BBC content on a non-exclusive basis, and do not prejudice algorithmic recommendations against it. BBC content would have to carry bold BBC branding, so that viewers know where it’s coming from. For the streaming services, this would not be much of a burden. In fact, it’d be offering up extra content for free.

Perhaps the biggest gamble though is that the BBC would get lost in the crowd without its own outlets front and centre, but I think this is a challenge it would have to meet head-on. The idea is that by focusing on trust, the BBC will succeed not because of its default position at the top of an electronic programme guide, but on the strength of its own brand and reputation as a trusted source of information.

Paying for it

“Sounds like a great unworkable fantasy, James! I mean, for a start, how would you pay for it?", I hear you ask. Good question.

In my mind, one way to do this would be to transition the BBC and it’s unbundled offshoots to something a bit like the Arts Council, funded through a combination of government grants and lottery funding.

One idea I heard somewhere (I wish I could remember where), that I quite liked, was to fund the BBC with an endowment. Essentially give the BBC an enormous pot of cash now, but then leave it on its own to figure out how to make money and spend it in the future. It’s a model that works for Harvard University and the Wellcome Trust.

I’d also let it continue funding itself through its commercial arm too, as it does now. I bet Netflix would pay big money for the rights to produce and publish Doctor Who13.

A sketch on an envelope

I imagine by this point, anyone who actually knows what they’re talking about is absolutely furious. I knew that by implying I had an answer to the BBC’s universality death spiral, I would almost necessarily have an unsatisfying answer.

There are countless things the BBC does that I have not addressed. What about its incredibly good R&D department? What about radio?14

Hell, how would this transition even work? On what timeline? What the hell do you even do with BBC One for fucks sake15?

It would be instructive at this point to go back to where I started this pair of articles: BBC Television Centre.

The story supposedly goes that the architect Graham Dawbarn first came up with the rough plan for the new building in 1949, sketching it out on the back of an envelope. The Television Centre site was an unusual wedge shape, within which this culturally important institution had to fit.

Vexed by how to do it, he drew a question mark — and staring at the page soon realised that this was the perfect shape for the new building.

With this in mind, I’d like you to consider this post not a complete solution, but a sketch on an envelope. Like Dawbarn, we can see the outer boundaries of where a BBC of the future will have to be built, given the constraints of the broader content ecosystem. If we want the BBC to continue doing the important things it does in the future, we need to figure out how what shape to fit inside.

If you’re read this far, well done! You should definitely subscribe (for free!) to get more of this sort of thing in your inbox. And hey, follow me on Twitter too, because my tweets are arguably even better than my Substack stuff, because they are shorter.

Special thanks to Allie Dickinson for kindly deploying her editing skillz on this piece.

I really need to figure out what my personal brand is here, as I write about a wide range of things and it feels like they have something of a through line, but I can’t work out what that through line is. Tweet me with your best suggestions.

Read this by Matthew Ball for a long essay on Disney’s IP pivot. It’s where I pinched this analysis from.

Seriously, try to list the biggest entertainment properties outside of gaming that aren’t owned by Disney. You’ll end up with a list that contains basically “Harry Potter”, “Star Trek” and “Jurassic Park???”.

Curiously, I was never much into Disney as a child, so all of the classic Disney films leave me cold. I don’t think I’ve even seen most of them, as my dad raised me on Batman instead. Oh, and I only saw Star Wars properly for the first time in my 20s.

And for fans of soft power, the BBC is also one of the most trusted news sources in the United States, second only to local news.

Thanks, internet.

Americans apparently subscribe to an average of 3.1, implying there could be room in Britain for more competitors. But already on top of Amazon, Netflix and Disney there is, of course, Sky. Plus a tonne of a smaller competitors, and the spectre of Paramount+ and HBO Max launching over here too.

This is slightly Apples-to-Oranges, but if the current TV licence is about £13/month, that puts it at the upper end of subscription pricing compared to Disney (£7.99), Netflix (starting at £5.99, going up to £13.99 if you want 4K), and Amazon (£79/year and you get all of the other Amazon services bundled in). I’m not sure that’s a price point where the BBC can succeed.

Just going to stress here that I think it is good the BBC is well funded! I like and support the BBC; I’m just stating the political reality that most people don’t think like me.

Well, we actually know that Apple and Google have won on distribution, as the end points mediating between content and people, but you know what I mean.

Yes the BBC already produces a lot of social media content, but much of it is to serve as marketing for the BBC’s traditional content. Imagine a BBC that is entirely focused on producing content for new platforms.

The best analogy to this I can think of is the post-1945 global institutions. Though NATO, the EU, World Bank, IMF, WTO, and UN have separate functions, they have created an architecture that has guaranteed post-war stability for 76 years.

An interesting subplot in streaming media is the relative decline of Netflix. Netflix scaled enormously when it was the only streamer, but now it is obviously losing market share to traditional media conglomerates wising up to streaming. One of the reasons it is doing so is because the old conglomerates are pulling their libraries from Netflix to host on their own service. Another reason is because it’s a new company, and it doesn’t have an enormous library of IP to mine compared to Disney, who can slap a Marvel sticker on anything and have a blockbuster hit.

BBC Radio has a budget of about £88m, not an enormous amount of money in the grand scheme of things, so could maybe work as an NPR-style organisation. As for R&D? I’d still include this as a broad function of the “trust” mission. By setting standards and ensuring technology is accessible, there’s real public service work there that would, on net, increase public trust.

I believe I’m actually followed on Twitter by a couple of people who work in the BBC continuity/playout department, I really like them, and their tweets, so I hope they don’t hate me for suggesting the BBC, in the long term, abandons traditional broadcasting…

One thing that would instantly open up a new avenue of funding today/soon would be to allow foreign access to iPlayer. There are rights issues for some content, of course, but there's a huge demand for that, and it needn't be at the £13/mo level if it's just to augment the licence fee/offset Govt. cuts to funding. It could be a step towards your unbundling of BBC content; renegotiate with existing licensees to say 'Hey, we're going to be offering our content in your country. You can still carry the stuff you have already licensed, but any future deals will be cheaper, and you'll still get exclusive-to-your-market access to boxset-type content that may not be on iPlayer at all times'.

Gonna be hard for people to trust the Beeb if it keeps fighting the so called 'culture wars' on the side of the reactionaries. (e.g. that transphobic news article they published)