How municipal bond markets can save Britain

The case for more fiscal devolution to build the infrastructure we need

POD! A super fun episode of The Abundance Agenda podcast this week. I make the case for why Manchester should bid for the 2036 Olympics as the ultimate Northern Powerhouse insurance policy, and we speak to architect Ivan Jordan about the problem with how we handle listed buildings. Listen/subscribe here.

Hello! I’m now back from my holiday and will have a fresh, scolding hot take for you once I have recovered from the jet-lag. In the meantime, my friend Morgan Wild, from Labour Together, has written this fascinating piece for my newsletter, making the case for how municipal bonds could keep Britain’s infrastructure investments on track and under control. It’s essential reading if you’re interested in growth, and how we can get Britain building again, so enjoy!

The basic problem of Britain’s political economy is that we try to run about half of it from one postcode. This leaves the British state overworked, overconfident and oddly underpowered. It tries its hand at everything and does very little well.

I’m a lefty. I think taxes are the price of a civilised society. Right now, I think higher taxes to invest in Britain’s future are the only way to get out of our current stagnation. We’ll be much happier and richer if we tax more today to reap the benefits tomorrow.

So I am equal parts terrified and delighted by the £1 trillion size of the government’s Major Projects Portfolio. Delighted because this government is investing more in the future than any other government since the 1970s, when every political incentive is to spend more today.

Terrified because of Britain’s track record. Only 2.7% of planned spending is on track.1 If things go really, unbelievably well, I think we might keep wasted spending to the tens of billions under the current system. In Whitehall, things have a habit of not going well.

This is a tier one problem with how the British state uses taxpayer money.

I believe this problem has a solution.

One that can give our second cities and big towns and perhaps even local councils power and agency again. One that can save the taxpayer billions of pounds. One that powered Victorian Britain and is used by every other major country.

I’m talking, of course, about municipal bond markets.

Whitehall controls everything and therefore does nothing well

When you want to do big infrastructure and housing projects, you need to borrow a lot of money.

Government borrowing is the cheapest borrowing you can find. You never need to worry about His Majesty’s Treasury paying its debts. It’s got so much revenue coming from so many different places. Honestly, we are so so good for it.

That’s the main reason for our current way of doing mega-projects. Borrowing is a big part of the cost and therefore this looks cheaper.

But that cheapness comes at a terrible price for the virtue of everyone involved:

Projects are only approved if the estimated cost meets strict budget constraints or fiscal rules, so departments have an incentive to be unrealistic about costs. This is known as ‘optimism bias’ or ‘strategic misrepresentation’ or ‘lying’. Once something is signed off it’s then much harder to cancel later on.

The Treasury knows this. It is correctly sceptical about all new spending. But that scepticism is a blunt tool. They’re trying to control a budget that is some 45% of GDP. They can’t do real due diligence.

The Chancellor has her own bad political incentives to cut capital budgets and prioritise day to day spending - an incentive that Rachel Reeves is, in my view, patriotically trying to resist. But a sword of Damocles rests over every major project if the Treasury needs some wiggle room.

Many good projects don’t get built, because the Treasury won’t sign off on the business case and no-one has the power to persuade or challenge them. Equally, bad projects that are the whim of a minister find it easier to get off the ground.

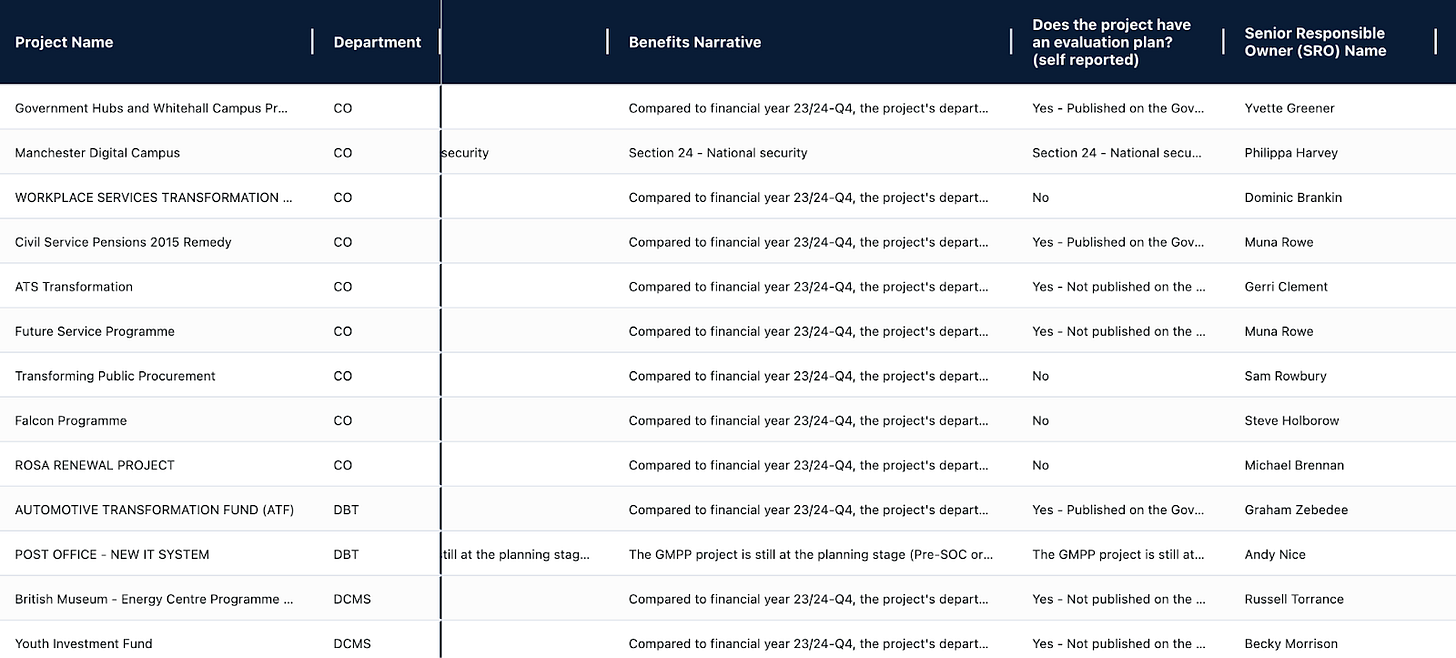

The state’s answer to this so far has been more process and compliance. We create ludicrous management spreadsheets to give the illusion of control. The most recent review of major projects suggests new requirements for evaluation before projects are approved as its main vehicle for improvement. The people running the projects don’t even bother following this requirement - understandable, when the state has never evidenced that evaluation is associated with cost control or delivery.

This spreadsheet is everything that’s wrong with Britain

We are misunderstanding the problem. The problem is not that civil servants are not working hard enough or are insufficiently procedural.

Instead, we need to give our nation’s great project managers skin in the game.

Municipalising finance

The Great Stink of 1858 inspired London to build the biggest sewer the world had ever seen. The smell was bad enough that London decided to task Joseph Bazalgette, Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, with building a solution, the sewer system that London has to this day.

This was the largest civil-engineering project of the nineteenth century. A public independent corporation with its own claim on future revenue made it happen - the exact institutional set-up we need again. Londoners’ coal and wine taxes were hypothecated to repay the bond. The market discipline was on Bazalgette to deliver.

The sewer was regarded as ‘the greatest metropolitan improvement of [Victoria’s] reign’ [Pall Mall Gazette].

This wasn’t a novel approach to public works. 50% of the market for gilts was by local government, compared to 5% now. Financing works this way is routine in other countries:

The US has a $4tn strong municipal bond market, financing everything from roads, energy and water, to airports and schools

Paris is halfway through building the Grand Paris Express, a 200km, 68 station extension, financed by €36bn bond issuance against local property and business taxes

In Sweden, Kommuninvest provides municipal financing of $50bn to specific, risk-bearing major housing, infrastructure, schools and hospital buildings

This is one way to give public servants skin in the game. The team delivering the project should also raise the finance. Their decisions matter to them - cost overruns mean higher local taxes - in a way that they don’t when they’re trying to talk money out of the Treasury.

Pension funds or other big institutional investors are also going to be much more intelligent lenders for individual projects. Their repayments are tied to the project’s success, whereas when they lend to central government they only care that enough tax is being raised to pay back debts in the round. Because they have skin in the game they will be much more flexible when things aren’t going to plan than the weary cynics at the Treasury can be.

These are old arguments. They were the historic case for private finance initiatives. But PFI had a reputation for cutting corners, because private equity’s interests did not coincide with the public interest unless the contract was watertight. Similarly, the amoral Aussies at Macquarie worked out that they could get better returns by overloading Thames Water with debt and walking away with a tidy profit. There’s a very reasonable argument to say the British state just isn’t competent enough to negotiate with private equity on big projects in this way; that we are forever Faust to their Mephistopheles.

We don’t need PFI to do these things. The public sector can achieve better results, as long as we get the right incentives in place.

Local power needs local incentives and local knowledge

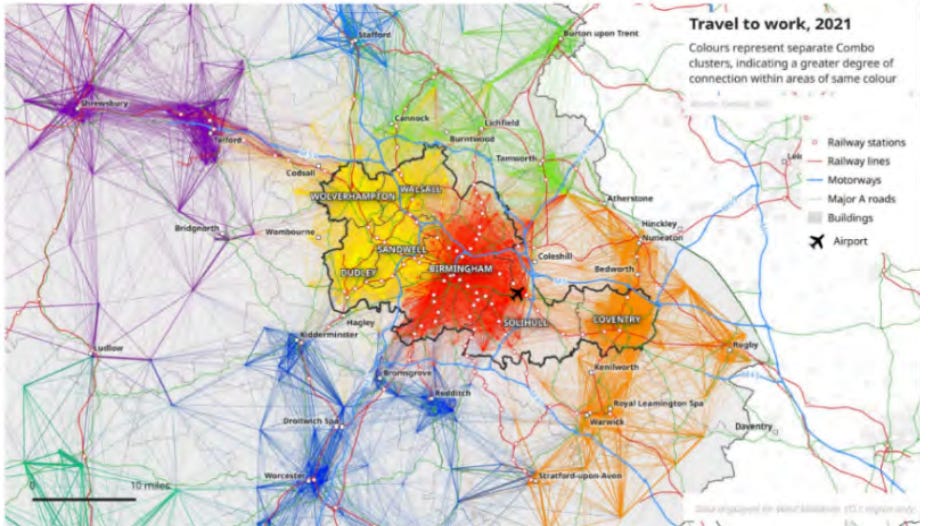

Does the West Midlands have one economic centre or several?

The West Midlands Combined Authority set out their theory of growth for the region earlier this year. Unlike most of these kinds of papers, it is a pleasure to read: full of specific, contestable claims from a team trying their best to understand the area’s economic malaise and fix it.

One of the biggest claims they make is that the West Midlands’ economy is polycentric: the Black Country, Coventry and (most significantly) Birmingham are jostling for position as an economic centre. They are clear-eyed that this is a disadvantage. Regions with a single centre tend to perform better. But for them it is a fact of life and therefore their strategy is to create a ‘goldilocks zone’ that maximises connectivity between these different centres.

The Centre for Cities thinks that’s wrong. Look at the size of Birmingham, they implore. That is the economic centre and West Midlands’ underperformance is a function of, in part, it being so hard to get to. Only 35% of residents can reach Birmingham city centre within 30 minutes - compared to, say, Munich where it’s 74%. That’s the way you’ll get the agglomeration benefits the region needs.

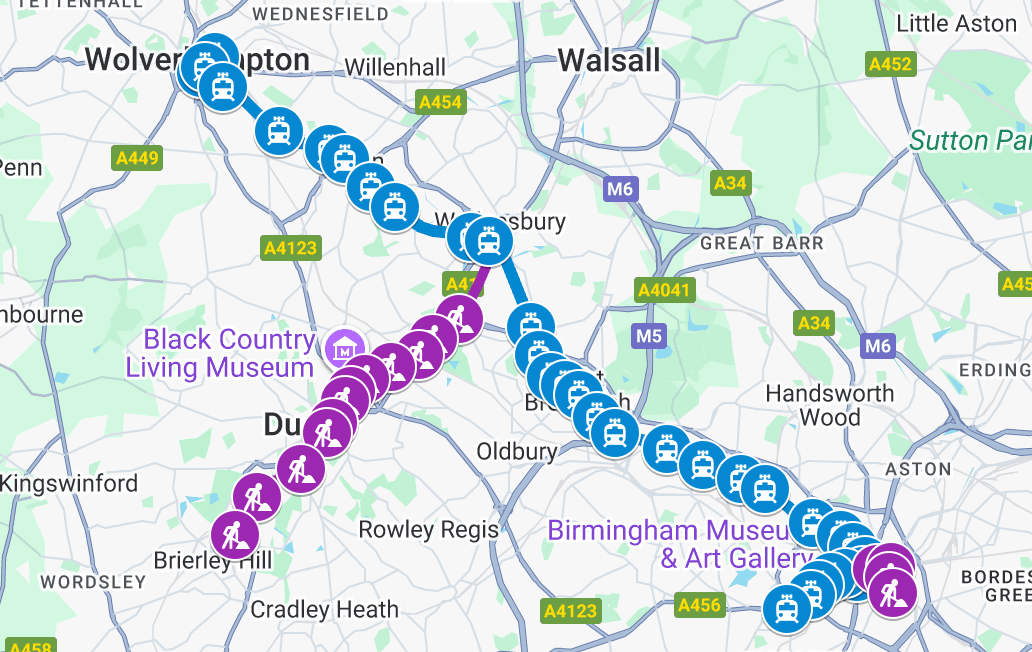

That makes a difference to correct economic strategy on things like transport. If the Authority is right, then the tram extension they are building from Brierley Hill to Wednesbury below is exactly the kind of investment that the West Midlands should be prioritising. It improves links both to Wolverhampton and Birmingham City Centre, at the cost of not doing as much to increase the number of people who can get to the centre in 30 minutes.

If the Centre for Cities is right, you would focus on what will expand Birmingham city centre and connection to it - denser neighbourhoods in the centre, congestion charging, improved road and bus networks. But that would mean worse transport links for deprived areas in the Black Country and sacrificing some of the benefits WMCA think follow from their analysis of economic geography.

I have no idea who is right. I’m just some guy at a think tank. Pretending things can be known from the centre is why we’re in such an economic state.

What I’d like is to trust that the local government will call this right. But they will have their own internal pressures and - given the money is being handed out from Whitehall - weaker incentives to spend with maximal wisdom. And the Treasury can’t really know or care either. It’s just a line item in a devo-deal.

We can solve this problem by giving the West Midlands skin in the game. The basic trick is when projects have future economic benefits (like fare revenue, or increased land values), tie the municipal bond repayments to those benefits. That forces a discipline from the West Midlands and investors alike: the best way to see a return is to know that this is a credible investment. The price of the bond is linked to the success of the scheme.

That bond can’t tell us what is best for the region in the round. There’s more to life than optimising agglomeration benefits. The West Midlands Authority is always going to have lots of competing pressures, not just its economic future. But it will make better decisions if it’s the one responsible for them paying off.

We often end up talking about devolution in a way that makes it sound like a nice fluffy agenda. It shouldn’t be. The mission is to create new engines of civic power that rival Westminster. Responsibility for your destiny means making choices more seriously than when the Treasury writes the cheques.

Barriers in our way

We are starting to move this way. New development corporations for new towns will hopefully borrow against future revenues from selling plots of land.

I think we should go further. Local mayoral authorities should borrow more directly, so that the market is pricing the actual risk and benefits of the project.

There isn’t a free lunch here. Project financing is always more expensive than government gilts. If the US is anything to go by, over time we can probably get this down to 0.5% higher than government borrowing.

Projects will look more expensive on paper. But we will more than make up for it in discipline.

We would need to fix two things to make this happen: fiscal devolution and accounting rules.

Fiscal devolution lowers the cost of borrowing because it convinces bond markets that local government has the revenue to pay them back. For these purposes, it doesn’t really matter what tax base we devolve, as long as there’s a decent enough cushion to fall back on. Ideally, it includes taxes that increase as a consequence of the economy growing - the ability to capture increases in land values, for example.

Our borrowing regime also makes this more difficult to fix. Part of the problem is that we classify all state debt the same way, encouraging the Treasury to put everything in the government gilt pile. Because our fiscal rules track the size of total government debt, the Treasury never wants to give autonomy away. But there’s one simple fix to this. As Thomas Aubrey, the wizard king of municipal bond policy, argues we can follow EU best practice by reclassifying the debt of public development corporations when their debts are financed by market revenues rather than general taxation. This won’t work for all projects - some of the projects will be financed by taxes directly. But it will help for some.

“Everything we can actually do, we can afford”

I love this quote from Keynes. It gets to something deep and important – that money is a convention we’ve invented to help us, not hinder us. Capital markets are incredibly useful fictions we’ve invented to coordinate, discipline and incentivise ourselves. We should absolutely use them to serve our ends. But financing is never the ultimate constraint. The real resources of society are.

There are constraints on what we can sensibly build. But some of our current ones are artificial - the Whitehall bottleneck on project financing and management being chief among them.

If we can replace that single bottleneck with local, powerful institutions, we can do as many viable projects as we choose to. When better wages force me to quit the day job and retrain as a construction worker, then we might have started to move enough of society’s resources. Until then, Labour’s got work to do.

Morgan Wild is Chief Policy Adviser at Labour Together.

If you enjoy nerdy dives into politics and policy, then subscribe to my newsletter to get more like this direct to your inbox. I’m not as smart as Morgan, but I try my best!

Calculated as a proportion of total lifetime project spend

This is a very good reason to bring in land value tax nationwide. Once the land values are taxed it shouldn't be too hard to add a supplementary tax based off the land value to go to the local authority.

This way the local authority will have a tax base that they can use to borrow against for projects such as a metro that will increase land values. They will also be incentivised to reduce barriers to making these projects happen and anyone who's land drops in value will get a tax reduction both locally and nationally.

I would like to see each scheme added onto any tax bill so that it is clear where the money is going but that will also help to hold local politicians accountable.

As soon as HS2 runs, relocate parliament to Birmingham for twenty years while the House of Commons is made safe.

That is bound to help Make the West Midlands Great Again.