Why the revival of Northern Powerhouse Rail could save HS2 to Manchester

Known Facts + Wild Speculation = Cope

Don’t worry, something new will be landing tomorrow, but I wanted to re-share this recent piece with you all, in light of The Guardian confirming that the government will be reviving the Northern Powerhouse Rail project.

It’s a significant moment – not least as it further confirms there might be something in the wild and irresponsible speculation below, which I originally posted in June. So if you missed it before, here it is again.

(PS: This is unrelated but The Abundance Agenda is a good one this week – Martin and I debate our biggest disagreement, over whether or not AI is overhyped – or a really big deal.)

(PPS: If you like nerdy stuff like this, then please do take out a paid subscription so I can continue writing every week! Paid subscribers will also get special paid-subscriber-only posts, and my semi-regular round-up of interesting links!)

So it’s official. HS2 has been delayed from its planned 2033 opening date.

This is very annoying, but is sadly not surprising.

Essentially, the problem is that overly optimistic forecasts for how long different parts of the project would take have knocked plans off course, which is what has sent costs out of control. And on a big project like HS2, these forecasts can make a big difference.

For example, you might have one contractor responsible for the civil engineering – the actual digging of the tunnels, or construction of the track bed. But if this takes longer than expected, the separate company contracted to install the tracks, signalling systems and other railway equipment, may no longer be able to work with the new dates. And once you multiply problems like this across the entire project, and the thousands of stakeholders that entails, it results in a huge mess.

This has been clear for a while, which is why last year former Crossrail CEO Mark Wild was parachuted in to take over HS2, and he’s spent his time since conducting a “reset” of the project, that will eventually set out a new timeline for building what I’ve heard described as a “minimum viable product” approach – getting from where we are now, to HS2 trains running between Old Oak Common (the massive new station in West London), and the new Birmingham Curzon Street station.

So now the expectation is that at some point in the not-too-distant future, Wild will deliver a report to the government with a new delivery date on it – and, according to Rail magazine, it will likely be 2036 or 2039.

But I’ve written about this before. So why am I talking about it again?

Weirdly, it’s because I think there might also be some good HS2 news on the horizon. Maybe this is just cope, or perhaps I’m just doing some wild conspiracy theorising – but I think the pieces are slotting into place to revive the HS2 leg to Manchester, which was famously cancelled by Rishi Sunak in his 2023 conference speech from, er, Manchester.

So please don your tinfoil hat, and join me as we go down the rabbit hole and save HS2.

Northern Powerhouse Rail

Our story begins with this one throwaway line in Rachel Reeves’ spending review speech last week.

“In the coming weeks I will set out this government’s plans to take forward our ambitions for Northern Powerhouse Rail.”

Huh? She didn’t elaborate any further, but as far as I’m aware this was the first time the current government has said anything officially supportive of the “Northern Powerhouse Rail” (NPR) project – which is also sometimes called “High Speed 3”.

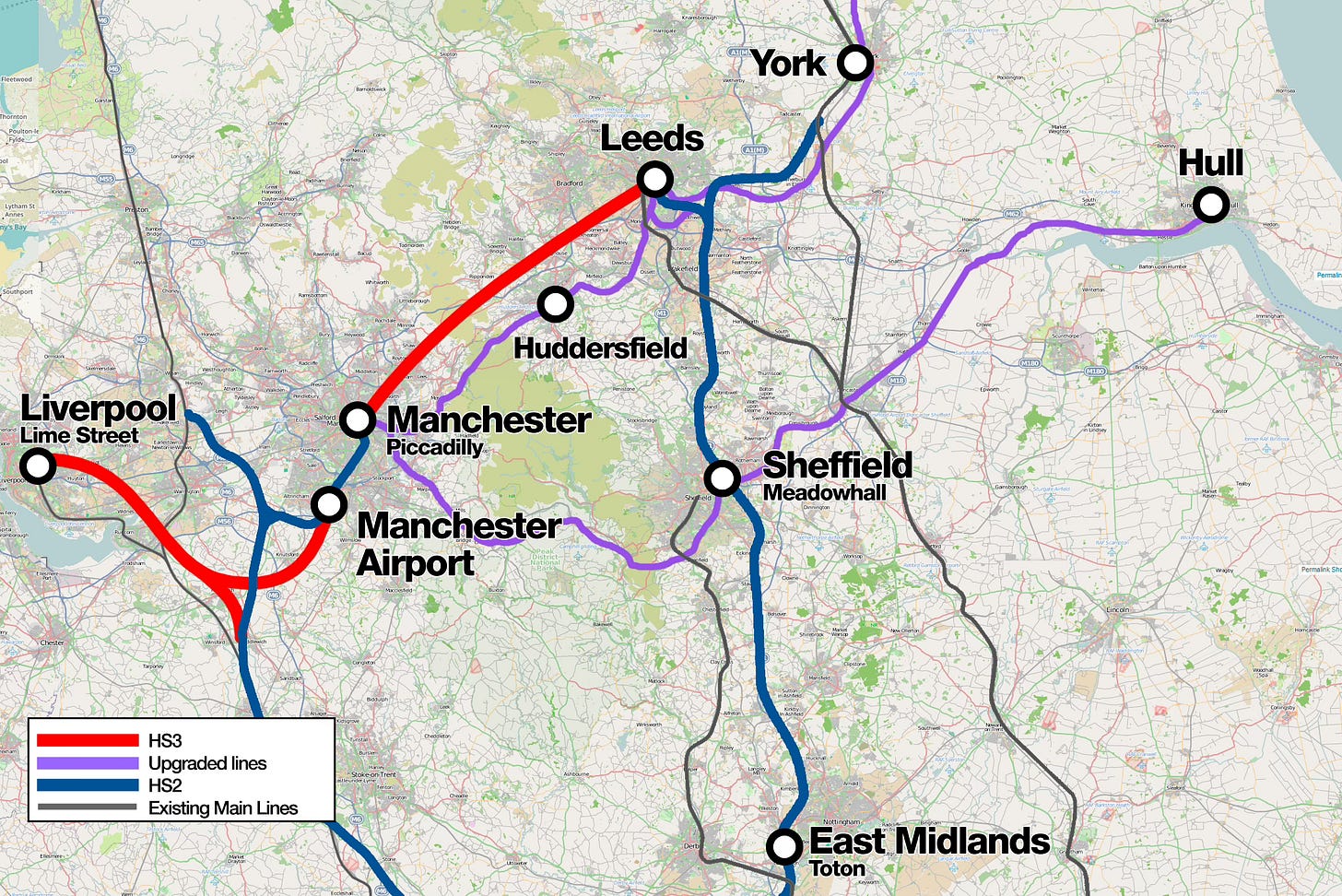

Here’s a map showing what it entails:

It’s an idea that was first proposed back in 2014, when George Osborne was Chancellor as a plan to boost economic growth in the north, and basically it’s a plan for a whole swathe of rail upgrades that would be incredibly useful.

For example, one of the major components of NPR is the upgrade and electrification of the Trans-Pennine line between Manchester and Leeds, which would take journey times from between 46 and 58 minutes now, to just 25 minutes – with an extra two trains per hour.

And then there’s the proposed construction of an entirely new line between Liverpool and Manchester, again increasing rail capacity from 4 to 6 trains per hour, and cutting the journey to just 26 minutes. Perhaps the most striking upgrade would be the time to Manchester Airport, which would go from 1hr35m from Liverpool, to just 35 minutes. And it would knock 40 minutes off the journey to the airport from Leeds.

So NPR was a very good idea – the sort of project that could more closely meld our northern cities together, and transform them into essentially a singular economic unit. This would be great for growth, as the laws of agglomeration suggest that when more economic activity happens in the same place, the richer people get.

However, in the years since the plan was first conceived, it eventually fell out of favour. In 2021, the then government changed strategy, and published a broader “Integrated Rail Plan”, which significantly scaled down all of Britain’s rail plans, including those for NPR.

So to hear Rachel Reeves say the phrase “Northern Powerhouse Rail” again was sort of notable in and of itself – it appears that ambitions are being scaled back up. And this is where things get really interesting.

The HS2 connection

It’s possible that Reeves used the phrase “Northern Powerhouse Rail”, but means something different to what it originally meant. It could be a political trick, a bit like how “Brexit” went from meaning “Leave the EU, but probably stay in the Single Market” on the 23rd June 2016, to “A death cult committed to national suicide” by the time the No Deal Ultras got hold of it. Politicians re-use labels all the time after all.

But on the face of it, it does sound as though the current government could be planning to re-commit to the full NPR programme, as part of the government’s forthcoming ten-year infrastructure strategy (which I understand could be published as soon as tomorrow).

One sign of this is that in the Spending Review, the government committed to the Trans-Pennine upgrade with £3.5bn in actual cash, which was a significant chunk of NPR.

And another is that, though no cheques have yet been written, the government has also given its rhetorical backing to the proposed new line between Liverpool and Manchester, which would travel via Manchester Airport and Warrington.

In other words, it appears that the emerging plan is to actually deliver NPR.

However, this is easier said than done.

To deliver NPR in full, it would require digging a new tunnel, 8 miles long and 33 metres below the ground to connect from Manchester Airport into Piccadilly station in the centre of the city. And it would require rebuilding Piccadilly station to construct a set of underground platforms for trains to arrive at. (See the picture at the top of this piece.)

If you think this sounds expensive, you’re not wrong – as far as I can tell, a price tag hasn’t been formally applied, but it’s the sort of thing that would typically cost several billion pounds. That’s why to justify the cost, when NPR was first proposed the original plan was that NPR trains would also share the tunnel with… HS2.

The mad speculation bit

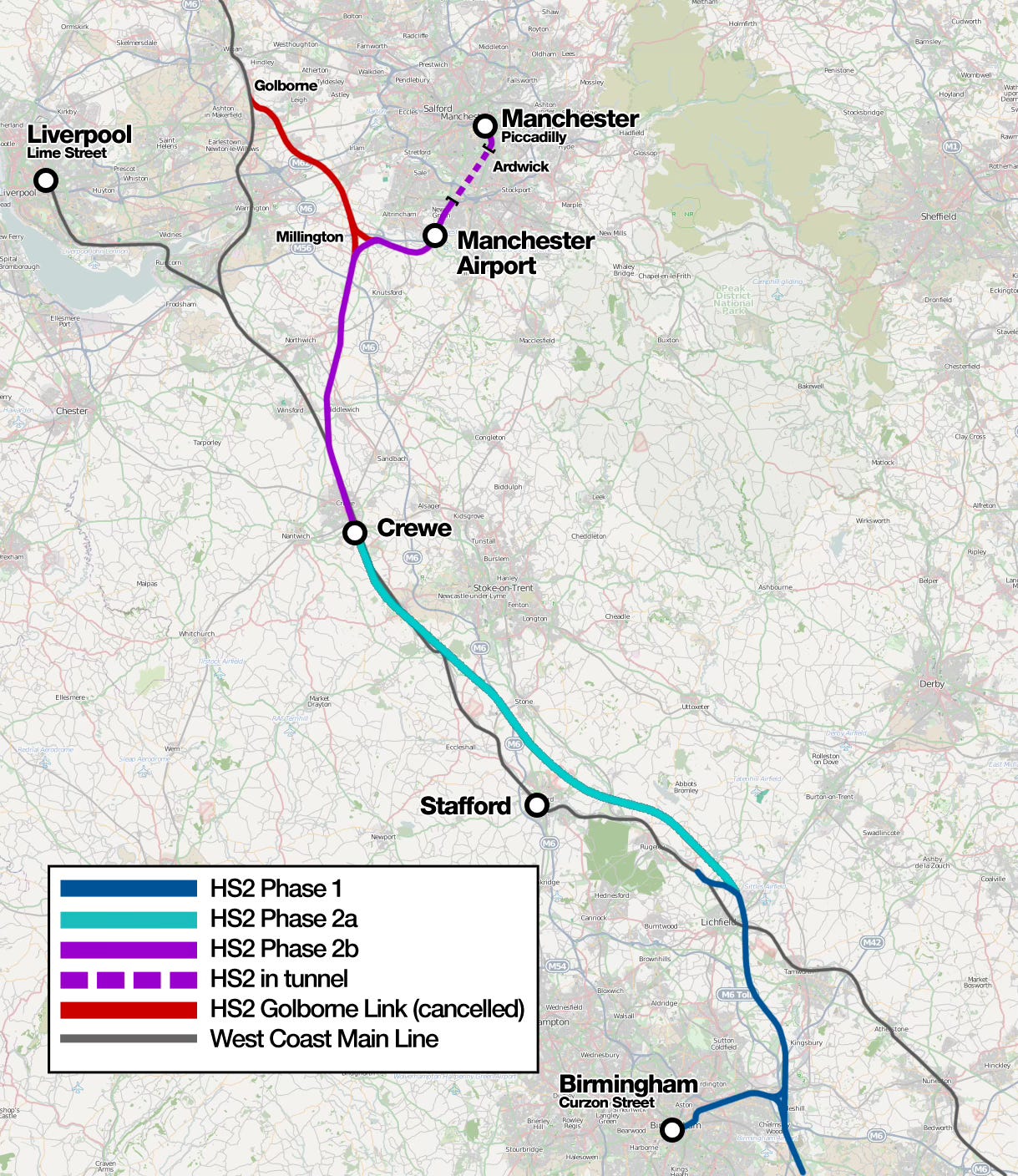

So here’s where the speculation gets truly wild. Here’s a map of the cancelled northern leg of HS2.

As things stand, the plan is to build only the section of this map labelled Phase 1 – the dark blue line into Birmingham that then goes a little further north to near Lichfield, as the line will join the existing West Coast Mainline at Handsacre Junction.

But now let’s take into account what Rachel Reeves is alluding to. Imagine shading in that part of the route from Manchester Piccadilly to Manchester Airport – the section of track shared with NPR. Suddenly, the most difficult, more expensive section of HS2 northern leg is taken care of.

For HS2, all that leaves is the section of the line between Handsacre and Manchester Airport. It’s a long way, but it goes mostly through the countryside – and not dense, expensive cities. It’s the relatively easy, relatively cheap bit of the line. And it will be the only part left to build.

So if NPR goes ahead – which it looks like it might – it would surely be crazy not to build this last remaining connection. And it would be crazy not to finish HS2 to Manchester at this point, given that under current plans, for complex technical reasons, once HS2 is done it will actually reduce capacity between Birmingham and Manchester.

So recognising that I’m fully wearing a tinfoil hat at this point, I can’t help but wonder… is the government planning to finish HS2 by stealth?

Hope and Cope

I’m sure that in reality, the plan isn’t quite so straightforward.

My excellent friend Michael Dnes, an actual transport expert has been speculating in a similar direction, but thinks it is more likely that at best it will mean the government maintains the alignment – essentially safeguarding the future route, so that some government in the future can one day, maybe, build the actual railway.

And similarly, he points to how most of the cash will probably have to come from private financing, which is more difficult than Rachel Reeves simply deciding to spend some money.

But the upshot of the remorseless logic of that one line in the Spending Review is that maybe – just maybe – could we actually get HS2 to Manchester after all?!

If you value my writing, please consider taking out a paid subscription so I can continue writing every week! A new paid-only post is landing tomorrow, so now is a great time to jump on board.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/aug/13/labour-to-revive-northern-powerhouse-rail-project-trains

This seems to suggest that the money for NPR is already pencilled in by the Treasury and also that it might be Liverpool to Hull