The Green Party is being bad at being Green

There's a contradiction at the heart of environmentalism

Nothing has infuriated me more recently than the cancellation of HS2’s eastern leg. The railway line, which would have linked Birmingham to Leeds, was canned by the government even though construction of the connecting section from London to Birmingham is well under way. So cancelling half of it now is a great way to suffer the vast majority of the pain of construction, while ensuring that the end result is also a bit shit1.

Most of our ire for this disastrous state of affairs should be directed at the Tories and the small-minded concerns of their backbenchers. But at least one dollop of blame should be slathered on a party that sits on my half of the political spectrum: The Green Party.

That’s right folks, I’m doing another vicious takedown of some nice and inoffensive people. Subscribe now (for free!) to my Substack to get more of This Sort of Thing in your inbox.

If you’re not as terminally online as I am, it might astonish you to learn that the Green Party are opposed to HS2. That’s right – a massive upgrade to the capacity of the entire rail network, the least carbon-intensive mode of transport we have, is opposed by the party whose whole schtick is to care about the environment.

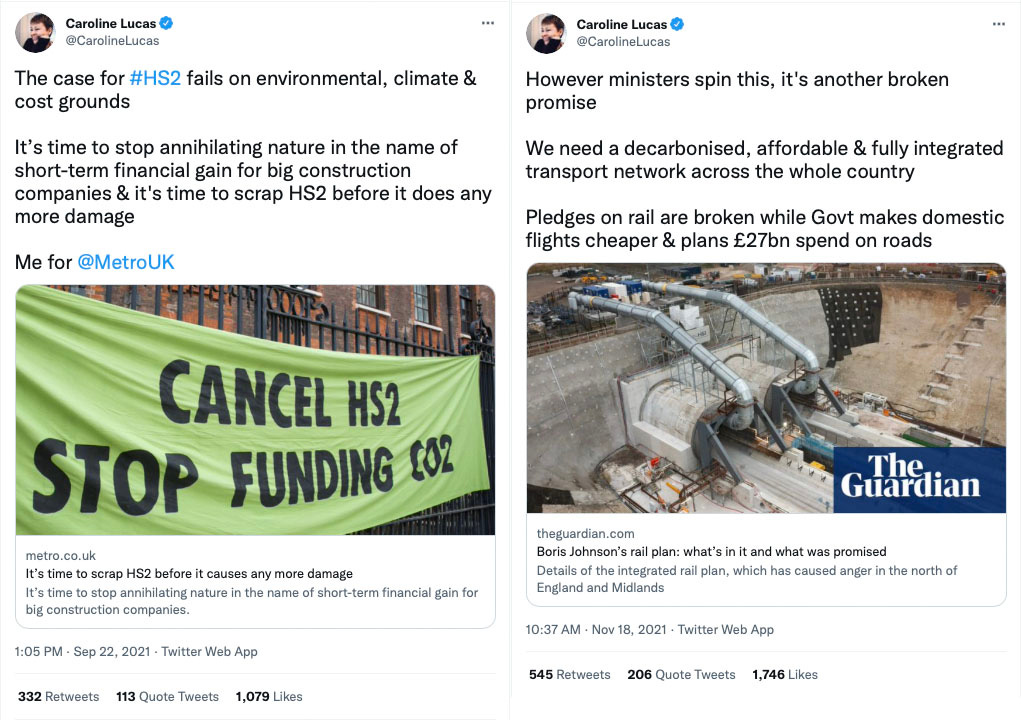

This is as crazy as it sounds, and is most hypocritically illustrated by the party’s former co-leader Caroline Lucas. In September, she wrote a column for the Metro attacking HS2, arguing in favour of scrapping it, and then in November, after the Eastern Leg was chopped off, called the decision “another broken promise”!2

Lucas’s column though is a useful document, as it makes plain the fatal contradiction at the heart of the Green Party3 and the severe problem with much of the discourse around the environment, particularly on the left.

Simply put, the unfortunate reality is that the goals of “Limit carbon emissions” and “Be nice to trees and don’t build anything” are mutually incompatible.

In her piece, Lucas runs through a bunch of arguments against construction that will be familiar to anyone who has even vaguely followed the debate: the destruction of historic woodland, trees getting chopped down, the construction of the line causing carbon emissions, and so on. But most of these arguments being piled on are basically irrelevant when it comes to climate change4.

For a long time, this contradiction has been papered over with relative ease by anyone who is sympathetic, like I am, to causes that fall under the ‘green’ umbrella. It’s not surprising that the people who want to save the whales and bore on about veganism are also concerned about climate change. All of these concerns are motivated by the same sense that we should be responsible stewards of our planet.

The problem is that these two goals require very different solutions.

We’ve got to build our way out

We already know what a world that has adapted to mitigate climate change looks like.

We need a world where more people choose to take public transport and ride bikes than use private vehicles. We need to replace the cars, vans and lorries that remain with ones that run on battery power. We need better insulated homes. And we need to generate renewable electricity. And so on.

But if we want these things, we have to actually build them.

And whether we’re building railway lines or factories to produce batteries, we will inevitably have to chop down some trees, tarmac over some fields and generate some upfront carbon emissions in the process5. A net-zero Britain is not a green and pleasant land, it’s an industrial estate in Slough without any chimneys, and an eight-lane motorway packed with battery-powered heavy goods vehicles6.

It might be the case that in some circumstances we can do something that is both good for carbon emissions and the broader environment, but ultimately this is a question of priorities. Which goal is more important? You have to pick one.

I mean, it feels awkward to actually articulate this, but given the potentially catastrophic consequences of climate change, we shouldn’t really give much of a shit about whatever specific trees7 are lost in the process of doing things that remove carbon emissions from the atmosphere8.

This goes back to what I said previously about the eschatological leftists: the lack of focus. I thought climate change was the most critical, existential issue facing humanity – so why are we pissing about worrying about the less significant, non-macro impacts when the only metric that really matters is the parts-per-million in the atmosphere of greenhouse gases?

The Degrowth Delusion

“But James! Can’t we have both? If we can persuade people to travel less or change their lifestyles, we won’t need to build all of this new stuff!”

No. The problem with what I’ll (perhaps unfairly) call the “Green” position on combining climate with a basket of other environmental concerns is that it only really makes sense in the context of “degrowth”.

This is the idea that economic growth should be deprioritised relative to environmental concerns. If we have less stuff, and consume fewer of the Earth’s resources, we’ll simultaneously reduce carbon emissions and do less damage to nature at the same time.

And this sounds appealing until you think about it for more than five seconds. I don’t need to go into the details here, as you can just read Tom Chivers’ superb evisceration of the degrowth movement instead. But the thrust of the reason why I find the idea of degrowth morally repugnant is that we should want people in the developing world to get richer for obvious reasons. “Economic growth” isn’t just numbers on an evil bankers’ spreadsheet, it is more people having more food, shelter, and better lives. Degrowth – by advocating for worse material conditions – implicitly wants to keep those people poor9.

Even if you don’t care about people in lower and middle-income countries, there is a more practical problem with degrowth too: there’s no way in hell to persuade people to go along with it10. People are not going to vote to make their lives worse, however worthy the cause11. And Britain aside, we’re not going to persuade China or India to temper their desire to get rich.

This means that we only have one option: we need to make economic growth sustainable by doing things like, to pick a completely random example, building high speed railway lines.

Buy Now, Pay Later

So we know that we need to achieve sustainable economic growth, and we know that we need to build the infrastructure to make this sort of growth possible.

When these constraints - these realities - are taken seriously, I think they point to a more productive way to talk about climate change12. It makes a strong case for getting out the national credit card and spending (spectacularly more) massively on decarbonisation now, even if the economists who know better than me would wag their fingers about having to pay for it later.

Why? Because climate change is the World War 2-sized emergency that justifies splashing the cash13. Now is the time to build new railway lines, insulate every home and whack solar panels on every south-facing roof in the country. Scientists should be drowning in money so that in 50 years’ time Dhaka, Miami and Norwich are not drowning in water.

Doing this wouldn’t just benefit Britain. Spending more now means more research and development, more scale in manufacturing, which will make things like batteries and solar panels cheaper. This means that as India, China and the rest of the developing world continue to grow, instead of burning coal they’ll have access to even more efficient solar panels and batteries, making fossil-fuelled growth less attractive.

The conflation of climate mitigation with a haze of other environmental concerns of varying importance is a brain worm that is deeply embedded, but one that must be defeated if we’re actually going to do something.

I hope that the new leaders and members of the Green Party will listen to their colleagues in Greens4HS2, otherwise it might turn out that the best thing the Green Party could do to help stop climate change is absolutely nothing at all14. If they continue to oppose HS2 to save a few plants along the route, they will be almost literally missing the wood for the trees.

Congratulations on reading all the way to the end! If you enjoyed it, please share this post, subscribe (it’s free!), and follow me on Twitter for real-time truth bombs and scorching hot takes.

If you enjoyed reading this you may enjoy my other writing on climate change:

Huge thanks again to Allie Dickinson for very kindly editing this post and stopping my most egregious crimes against grammar from getting through.

The only, absolutely crucial thing you need to know about HS2 is that it has a stupid name. The point of the project isn’t really about speed and getting to Birmingham slightly faster. The more important thing is that it increases capacity on the rail network. When it is finished, long distance trains will run on the new tracks, and it will enable more local services on the existing West Coast Mainline, making rail travel more viable and reliable for loads of people. And for reasons I’m not nerdy enough to explain, HS2 will also have a knock-on effect on rail capacity in basically the entire country. So even if you don’t live near it, you’ll probably benefit from it.

Before anyone says it: The “why not build [other railway line] instead of HS2” argument doesn’t work here either. Building anything involves building on nature, and I’m 100% confident that even if HS2 were cancelled the money magically redirected to, say, building railways in the North, similar NIMBY complaints would immediately emerge.

I just want to add some slightly-too-late throat clearing here about how while I’m having a go at the Green Party, I think everyone I’ve ever met who has been involved with the party, up to and including very brief interactions with two former leaders, has been lovely and I like them a lot. I’ve even voted for them a couple of times on the basis that the “Green” name is a good blunt instrument to send a message that climate change is important. So, er, I hope you will forgive my spicy take.

The one more relevant point, about the embodied carbon emissions from the construction of HS2 not paying off are contested. Here’s HS2’s rebuttal.

The construction industry is actually really, really bad for carbon emissions during the construction process - which I did some actual, proper journalism on here.

Or maybe lorries connected to overhead power lines, like the ones Tom Scott recently made a video about.

If HS2 required the destruction of large swathes of the Amazon rainforest, it might be worth taking into greater consideration. But as supportive as I am of HS2, I think extending it to the Amazon rainforest wouldn’t really work, as there are not enough population centres to link to, and the branch line would have to be incredibly long and go under the sea.

Obviously this is HS2 Ltd saying it, and they have a vested interest so take this with a grain of salt if you want, but they argue the ancient woodland thing is nonsense anyway.

Though I suspect if you were to ask a degrowther point-blank about this, they would squirm and avoid stating the logical outcome of their position, rather than defend the implicit conclusion of what they are arguing for.

No there is not a pathway to completely transforming the electorate and political consensus before it is too late to stop climate change, as I wrote previously.

Yes Brexit made our lives worse and people voted for it, but voters wrongly believed that it would make their specific lives better by getting rid of the scary foreigners. You will never persuade a critical mass of people to vote for degrowth because the entire pitch for it is “make your life literally worse now, for some abstract good for other people in a few decades, maybe”.

For a start, if we assume that degrowth ain’t happening, maybe instead of millionaire travel documentary maker Joanna Lumley scolding people earning less than her to fly less, we could accept that aviation is only 1.9% of emissions and the hardest sector to decarbonise, and instead pile cash and attention into sectors we can decarbonise more easily.

I think my least favourite argument deployed against HS2 is when suddenly and inexplicably left-wing people start complaining about the price tag (which will probably hit £100bn). It’s just super weird how they suddenly become budget hawks when money is being spent on something they don’t like. And I mean, if lefties did ever manage to actually win an election and wanted to start nationalising broadband or making university tuition free or whatever… how much do they think that is going to cost?

You might be wondering why we should care about what the Green Party think, given it is a minor party. I think that it is important because of the rhetorical power of the name. The “Green” name owns “the environment” as an issue - so I think even if people aren’t voting for the party, the words of the party who represent “the environment” carries an out-sized rhetorical weight and ability to shape the discourse.

Simply put, the unfortunate reality is that the goals of “Limit carbon emissions” and “Be nice to trees and don’t build anything” are mutually incompatible.

Sorry to come back to this so many months after it was published, but I've just realised something.

They aren't fundamentally incompatible; there is a third alternative: "become a lot poorer".

If we abolished cars and don't enhance public transport, then people just can't travel as much. If agriculture can't use tractors or fertiliser or pesticides, then it will need far more people, which is good because that will give all the people who can't commute to their jobs any more something to do - move to a village and start working on the farms.

If we get rid of fossil fuel power and we don't cover land with solar panels or wind farms, then we just have less electricity. Which means we are much poorer.

There are definitely a fraction of people within the Green movement (green haters tend to call them "crusties") who have very little carbon emissions but get there by just being poor and giving up many of the amenities of modern society and using a lot less energy.

I don't think we can understand how they come to believe what they believe without an appreciation of both the left-coded ("crusties") and right-coded (old-style conservationists; the sort of person with an AGA and no central heating) versions of this viewpoint.

It’s not just HS2. When it comes to genetically modified crops or nuclear power, the greens persist with irrational policies.

Degrowth is ultimately a racist and anti-humanist policy.

Thank you James for typing what many others have privately (and not so privately) thought.