This is how we pay for the Bakerloo Line extension

One weird trick can extend the Tube, level up the north and make the Treasury happy.

POD! On The Abundance Agenda this week, we talked about, well, extending the Bakerloo line – so you can hear Martin and I talk more about the below. Plus our very special guest was none-other than the excellent Sam Freedman. So it’s a really great time to subscribe and listen! [Apple] [Spotify] [Substack]

If there were a prize for London’s least-loved Tube line, it would probably go to the Bakerloo line.

This isn’t because of delays, overcrowding or the dog-poo-brown colour scheme. The problem is that it seems to have been forgotten about.

Take the actual trains running on the line, which, astonishingly, are now over half a century old. And then look at the Tube map and you’ll see that… the Bakerloo doesn’t appear to have actually been finished.

The Northern line runs all the way from Edgware in the north to Morden in the south of London. The Central line connects the suburban outposts of Ruislip and Epping. The Piccadilly line will take you all the way from far-flung Cockfosters to Heathrow Airport.

And yet the Bakerloo goes from Harrow & Wealdstone to Elephant & Castle, just on the south side of the river, on the edge of Zone 1… and stops.

I’m obviously not the first person to notice this weird anomaly. Since the line first opened in 1906, numerous plans have been made to extend the line deeper into South London, which have so far amounted to nothing.

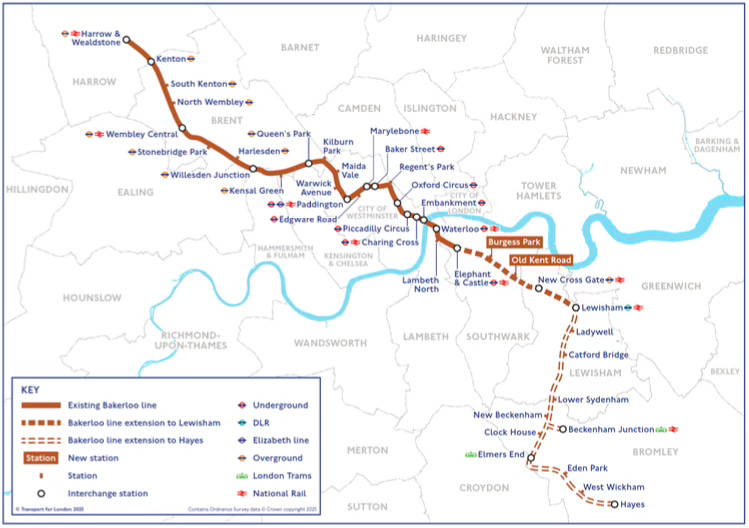

This includes the most recent attempt to reheat the issue. Over the last decade, Transport for London (TfL) has put together a detailed plan for the extension. In 2015, it published the ‘preferred’ route, which sends the Bakerloo down the Old Kent Road to connect with New Cross Gate and Lewisham. In 2019, a more detailed consultation pinned down exactly where the stations, tunnels and access shafts would go, and even announced some preferred names for the future stations.

Then, finally, in 2021, the route was formally safeguarded – legally protecting it from any new construction that would render it unworkable.

Yet despite all of this work… nothing has happened. There is no army of hi-vis construction workers digging holes in Southwark. There are no Tunnel Boring Machines inching through the South London clay. And it is all because of the elephant (and castle) in the room: How the hell are we going to pay for it? The current thinking is that it will cost in the region of £13bn – not too shy of the £19bn it cost to build the Elizabeth line.1

However, now there might finally be a credible answer, and this week I’m going to tell you about a bold new proposal that could not just finally finance the Bakerloo extension – but it could pay for other infrastructure in London, and even support the government’s levelling-up regional rebalancing agenda in the process too.

Like nerdy writing about politics, policy, infrastructure, transport and tech? Then you’ll like my newsletter. Make sure you sign up (for free!) to get more of this in your inbox.

TfL’s Bakerloo plan

Before we get into the big idea, let’s spend a moment appreciating just what a good idea extending the Bakerloo line is.

As per the map at the top, TfL’s plan is to dig a new tunnel, creating two new stations along the Old Kent Road, before interchanging with the existing New Cross Gate and Lewisham stations. Then there are already plans for a second extension, which would connect the newly elongated Bakerloo to the existing Hayes line, which would add another ten stations to the line.

So what does this mean in practice? Essentially, I think it’s as close to a no-brainer of an infrastructure project as it could possibly get. Not only would it improve connectivity for existing residents – who are wildly supportive2 – but it would create an enormous opportunity to increase London’s housing supply.

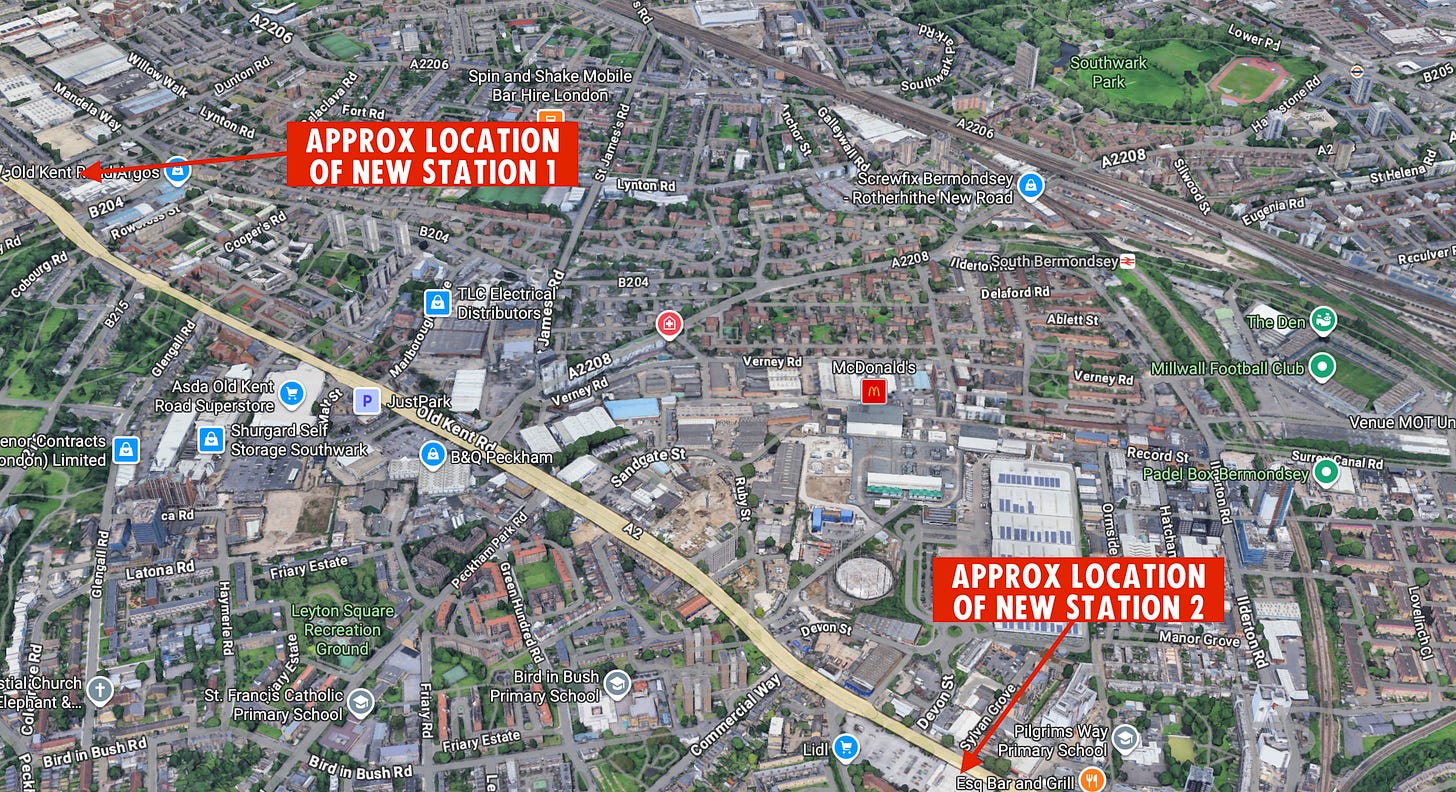

For example, the yellow road below is one section of Old Kent Road today. Despite being in Zone 2, it’s extremely low-rise, and even though it is on what is already a major transit corridor, much of the surrounding land is industrial estates and warehouses:

But here’s what one architectural firm thinks that it could look like if the two new stations were built:

To be clear, this specific render is not a final design. The specific design here does not matter. What’s important is that it makes it clear that if the industrial units were replaced, there is potential for thousands of new flats.3

And there are similar opportunities running the length of the line.

For example, Lewisham is already a major development area – over the last two decades, the town centre has significantly densified, and is now home to a number of tall buildings, with plenty of scope for more.

Then, if that second phase is built, to Hayes, it could also be transformative. Bromley – the borough that seven of the potential new Bakerloo stations are in – is currently the least densely populated London borough. So there’s obviously enormous scope to build there, and create new, denser communities that are extremely well connected by rail.

Paying up

This is all to say that extending the Bakerloo is an insanely great idea on the merits. But that brings us back to the difficult question of how to pay for it.

This feels like a particularly impossible question at the moment. It’s unlikely that the Chancellor will stump up the cash, given the state of the public finances. And it would no doubt be politically tricky, given the HS2 mess, and the fact that only a few years ago London got another, very expensive new Tube line.

However, there is good news. Some clever people have been doing some serious thinking about how to solve this problem.

Enter ‘London Unchained’, a new report that has been published today by the think-tank Labour Together in partnership with the YIMBY Alliance, and is co-authored by James Howat, John Myers, Kane Emerson and Jack Shaw.4

What’s the big idea? Somewhat counterintuitively, the idea is that the government in Westminster shouldn’t actually pay for the Bakerloo extension at all. Instead, given that London is the richest and most successful part of the UK, the government should give the Mayor more ‘fiscal autonomy’ – or in other words, new powers to raise the cash, without the need to turn up outside the Treasury with a begging bowl.

And there are numerous ways London could raise money if it were allowed to.

For example, the authors advocate giving the Mayor new ‘Land Value Capture’ powers. This is the idea that because the extension would massively increase the value of nearby land, as living or working near a Tube station is desirable, it makes sense that the windfall that landowners experience should be used to partially pay for the new line.

It isn’t a new idea. In fact, it’s basically what happened a century ago when the Metropolitan Railway (which later became the Metropolitan line) was extended out of London. When the line was built, the railway company bought up all of the surrounding land and sold houses on it for an enormous profit – which it used to pay for the railway it had just built.

However, it doesn’t just have to mean buying the land. Value can be captured in less hands-on forms too. It could simply be a tax levied on people or businesses nearby. This is similar to how the Elizabeth line was funded – a one-off levy was piled on to business rates in London to pay for the new line, on the basis that the entire city would grow wealthier from the new line.5

So, the paper argues, why not give London the power to do this for other projects too?

But this isn’t the only idea in the paper.

For example, what about tourist taxes – which are common in other countries, but not allowed in England?6 I think a tourist tax is a brilliant idea, as not only could it raise millions of pounds to spend on infrastructure that tourists will also enjoy, but it’s the sort of tax that absolutely no one thinks about until they’re standing at a hotel reception desk, by which point it is too late to go home.

And the paper also calls for local government to be given more discretion over council tax, so that it can be hiked as long as it is ‘hypothecated’, with the extra cash put into a separate pot specifically to pay for the Bakerloo line extension or other specific infrastructure projects.

There are a tonne of other ideas in the paper too – I won’t go through them all here, so check it out – but I think there is one other particularly interesting point: that even if all of these powers were devolved, there’s still the question of how you’d make the Mayor of London actually use them – and how you’d make London boroughs comply.

For example, you can imagine how the Mayor may not want to risk imposing extra taxes, for fear of making them unpopular. Or perhaps7 Bromley will have NIMBY councillors who resist development.

To get around this, the paper proposes shifting the incentives by further empowering development corporations, which are set to be a big deal after the Planning Bill passes into law. And central government could also tighten the various planning rules to essentially require dense housing development along transport corridors – which is exactly where we want the development to be.

Regional rebalancing

Now for the twist. Though London Unchained uses the Bakerloo line extension as its major case study, the implications are actually much broader.

I don’t simply mean in terms of how the same mechanisms could also be used to fund other critical bits of infrastructure that we can’t afford, like the extension of the Elizabeth line to Ebbsfleet and North Kent.

But it could also support the government’s ‘rebalancing’ agenda – which is the new name given to what we used to call ‘levelling up’: the idea that we reduce regional inequality between London and, well, basically everywhere else.

The reason the proposed policies also make a difference here goes back to the nation’s finances. Imagine you’re the Chancellor of the Exchequer for a moment.

On the one hand, you don’t want to spend too much on infrastructure, as you need to maintain Britain’s fiscal credibility, lest you accidentally cause a Liz Truss situation.

Then there’s the myriad of things the government needs to spend money on, which is often difficult politics. For example, any government that cut the NHS would be quickly thrown out of office – and because of Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, we now need to spend more money on fighter jets, tanks and drones.

So winning the argument for new railway lines is always going to be difficult. And even when talking specifically about transport infrastructure, there are awkward trade-offs.

For example, Tim Leunig wrote an enjoyably provocative post recently about £100m of improvements to Darlington station. Though Darlington is a sizeable northern town, Tim argued that in pure bang-for-the-buck value for money terms, the money would be better spent improving the station in Catford, an obscure London suburb, as it has more commuters.

And this is essentially the story of why there have been numerous plans for “Northern Powerhouse Rail” over the years, with different names. They’ve been abandoned every time, as London has always tended to win the political fight.

However, this is also why the London Unchained proposals could make a big difference. If London has more fiscal autonomy and pays its own way, then government spending is no longer a north vs south fight – the central government can use its cash to invest in infrastructure in the north.

And for complicated accounting reasons related to fiscal rules, the authors say that in many countries, if debt is owned by development corporations, it can conceivably be kept outside of core fiscal rules – which would neuter potential Treasury concerns over investing money on transport infrastructure.

London Unchained

I was very excited when I saw this paper ahead of its publication.8 In fact, because I was so excited, Labour Together actually asked me to write the foreword to the report, which was very flattering to my enormous ego.9

What I like about the paper though is that it really does seem to chart a plausible path from where we are now, to one where the Bakerloo line extension – and a bunch of other important transport projects – could actually be built.

In other words, this is important work. Figuring out how to get projects from crayons on a map to functional railway lines should be an urgent priority. This is because even if we started digging today, TfL only ‘expects’ the line to be open by 2040 – by which time I once expected to be holidaying on the Moon, not struggling to get to fucking Lewisham. And it will be even later if there’s no money to pay for it.

So let’s give London the fiscal autonomy it needs. Let the capital look after itself, so the government can focus on investing in infrastructure in parts of the country that need it more.

And let’s – finally – finish the Bakerloo line.

If you enjoy nerdy politics, policy, transport, infrastructure and tech takes, you’ll like my newsletter. Subscribe (for free!) to get more direct to your inbox.

We also talked about the paper on this week’s episode of The Abundance Agenda. Listen to it on Apple, Spotify and Substack.

The £13bn comes from the paper I’ll talk about in a moment, which has taken estimates for the two phases from 2021, and uplifted them to 2025 numbers.

Amazingly 89% of the consultation responses in 2019 were positive – which is not only the sort of numbers that HS2 could only dream of, but even more surprising given the profile of the people who usually respond to boring council consultations.

Exactly how many isn’t clear, though the “Back the Bakerloo” campaign reckons it could mean as many as 107,000 more homes across the entire extended line.

I know what regular readers will be thinking: Haven’t I written about ideas out of LT recently? Like their digital ID proposals, and the Sunday trading poll they commissioned off the back of my writing (!).

Well, yes. But it’s not my fault if that is where the interesting ideas are coming from!

Needless to say the actual implementation was more complicated and not every company paid the roughly 2% tax, and as I understand it, major beneficiaries like Heathrow Airport contributed via a more bespoke arrangement.

Scotland added a ‘local visitor levy’ in 2023.

Let’s be real, it’s hardly “perhaps” and more “with grim inevitability”.

I suppose I’m a Westminster insider now people show me new papers before they are published? I guess I’ll have to use my insider status to tell you who the deep state is going to allow to win the next election in my next post.

No money changed hands, which is why I’ll still happily criticise the government for not walking the walk on some really obvious pro-growth, pro-innovation measures.

Tim Leunig on Darlington is doing the HS2 problem of merging the fixing of multiple problems into a single project which massively increases the total figure to justify cancellation.

Yes there is a new station and car park but the reason for them are 1 - expensive improvements to straighten the tracks at Darlington, 2 removing (most) Teesside services from touching the ECML. That requires moving the station to the East which makes the old carpark useless.

So the station is then a relatively cheap change to facilitate line improvements. And the irony is that for me the service will deteriorate as if it is raining I will now have to stand in the rain to catch my train (they ran out of money so the new platforms don't have a roof all the way down the platform).

Hello, Bromley resident here. Last time this came up, the leader of the council said that if the Tube was extended into the borough it would lead to the "manhattanisation" of Bromley. As if Manhattan is a bad place? *eyeroll* Bromley Tories are already firmly against it and any development will have to happen over their heads. It's hard enough just getting a new zebra crossing outside of a school down here...