We should let the government actually do stuff

Delivery, not deliberation

Here’s a graphic that struck fear into me, when I saw it earlier this week:

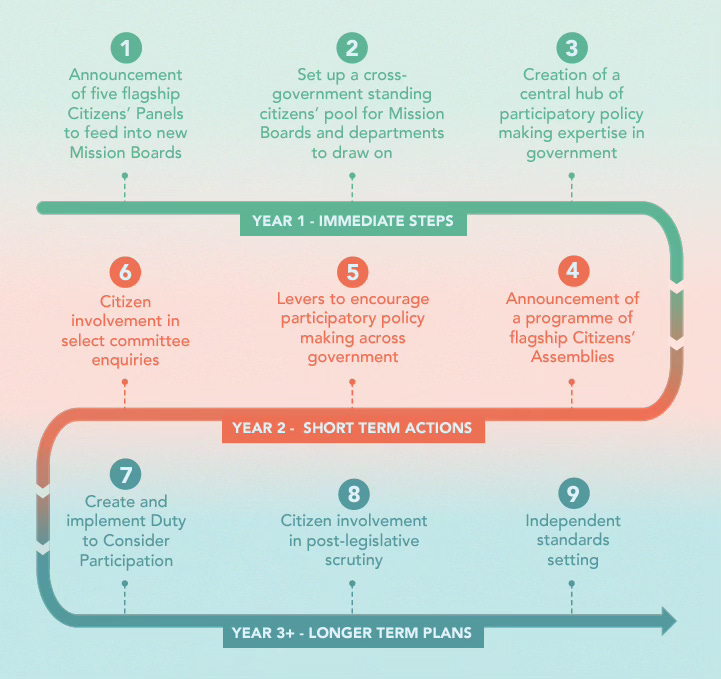

It’s taken from a new whitepaper published by the think tank Demos, and it proposes a “roadmap” to “embed public participation in national policy making”.

The argument is that given the scale of the challenge facing Labour in office, it is going to be important for the government1 to maintain public trust, and bring the public along with it, as it develops policies and makes difficult decisions.

The paper goes on to suggest a number of different mechanisms to do this, including organising Citizens’ Assemblies to tackle big issues like migration and climate change, and letting members of the public participate in Select Committee inquiries in Parliament.

It also suggests the immediate creation of five “Citizens’ Panels”, each composed of a hundred randomly selected, and demographically representative, members of the public. Each panel would feed into the “Mission Boards” that Keir Starmer has created to drive the delivery of Labour’s five stated missions.

In other words, Demos’s proposals have noble intentions, and set out some serious ideas for changing how policymaking in government is done. The paper was clearly the result of a lot of hard work by a lot of clever and talented people.

So I feel slightly bad about the fact that I’m now going to be a massive dick about it.

Because I really hope that Keir Starmer ignores all of the proposals and throws the paper in the bin.

If you like nerdy policy takes like this, then subscribe (for free!) to get more to your inbox, assuming Demos don’t hunt me down and break my fingers.

Death by consultation

I’m already on record as someone who is not a fan of Citizens’ Assemblies – which are the much talked about idea that we can select members of the public like a jury, and use them to determine the direction of policy.

But my scepticism about the Demos proposals is broader than that. I strongly reject the premise that what the British government needs is more “participation”.

Why? Because part of the reason why Britain is currently so broken and sclerotic is due to veto points already built into the system. The policy development process in government departments already involves endless rounds of meetings with stakeholders. And then when new laws go through Parliament, there is by design a long deliberative process as legislation is subject to multiple readings in the Commons and the Lords.

Now don’t get me wrong, there is obviously an important role for scrutiny and consultation in government. I’m not proposing we scrap democracy – even though it means that Simon Jenkins is allowed to publish his opinions in the Guardian.

But I also think it’s clearly true that unless the desire to consult is specifically reined in, every complex bureaucracy will ultimately tend towards creating more opportunities to talk and delay, instead of actually doing something. After all, we all have a human desire to be liked – and we think that more people will like us if we are perceived as fair and open when making decisions that impact people.

However, this desire to reach out and listen can also have negative consequences. If we inject too many veto points into a process, it just makes it impossible to do anything.

We can see this at its most darkly parodic extent in the planning system. In that case, a massively elongated process has led to a situation where it would make more sense to measure infrastructure delivery on a geological timescale.

For example, imagine if 61 year old Keir Starmer announced today that it is his intention to build, say, Crossrail 2, a long-proposed underground railway linking Hackney and Chelsea. If he lives until he is 80 – the average male life span in the UK – he will very likely be dead before any trains start running. And there probably isn’t a dog alive today that will ever ride on the planned Bakerloo Line extension to Lewisham.

Crucially though, this tepid pace isn’t just because digging tunnels or physically surveying the ground is time consuming. It’s because baked into the process is an endless need to wade through layers upon layers of community engagement meetings, legal notifications, environmental reviews, and committee meetings – and then face down appeals and judicial reviews, where at each point the development can be slowed down or even cancelled by someone saying “no”.

I’m sure Demos would disagree with my characterisation of added layers of “participation” as analogous veto points they want to add to politics more broadly, But functionally this is the case: The more a process has to stop and talk, the slower actually doing stuff happens.

And my view is that even if we think more consultation is a good idea in principle – in practice it is easily possible to have too much of a ‘good’ thing.

Differing interests

There is another elephant in the debating chamber. Part of the promises of greater “participation” is that it is a mechanism to find consensus. But.I don’t think it’s clear whether talking even more about some problems can actually build a consensus in the first place.

For example, the Demos report says the below about “facilitated deliberation” – which is one of the key ingredients it identifies if we are to have “participatory” policy making:

Participants are supported through a facilitated process to consider and weigh up different perspectives and discuss with other participants. The process is well structured, with a clear progression through learning and deliberation, to decision making. The process allows time for plenary feedback, so that participants can hear views from all other participants.

This enables them to come to informed judgement, think beyond their own interests, and give a view on what is most important for the system as a whole – just as policy makers themselves must do when making decisions.

We wouldn’t bother having ideas or writing Substacks if we didn’t think that reasoned arguments couldn’t change minds, but I think the tell here is the phrase “think beyond their own interests”.

Leaving aside the challenge of scaling this deliberative model to change minds with the wider public2, I’m just very sceptical that this at all reflects how people develop and hold opinions.

This is because even if you have a persuasive argument on paper and can persuade people to “think beyond their interests” during a meeting, the reality is that what matters more is our material circumstances. That’s why I used to swear blind against all evidence that my Gamecube was better than my friend’s PS2 – because that’s what I had under my TV.

And I think the same is true for how we process political arguments. Even if you understand intellectually that, say, Britain needs to build more houses, or that we need to introduce a system of road pricing, the reality is that once the bulldozers arrive in the field next to your home, or once you see a new outgoing on your bank statement, its very unlikely that you’re going to be happy about it.

That’s why even seemingly intelligent people will rationalise transparently self-serving arguments like like “yes we need more houses, but this isn’t the right place”, or “Donkey Konga is an underrated classic and is much better than Grand Theft Auto.”

And this tension gets at something I think advocates for participation/Citizens’ Assemblies often miss: The reason we have politics in the first place is to manage the conflicting material interests of different groups. And sometimes it requires difficult choices about which side wins and which side loses. There can’t always be a “consensus” position.

So I admit I am sceptical of the idea that increasing ‘participation’, or adding more layers of consultation, will increase trust in politics. I can believe that people may wish to feel more like they are being listened to – but I’d bet that what they really want is to get their own way.

Delivery is legitimacy

This all said, Demos is right about one thing: Trust is a real issue we need to worry about.

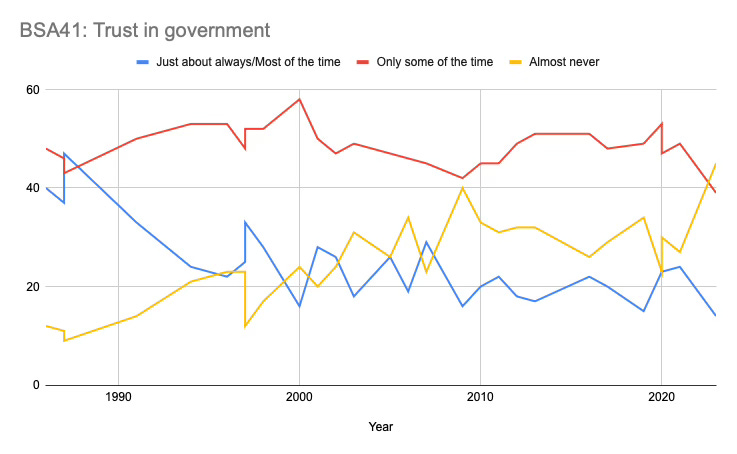

In its report, Demos cites research from the British Social Attitudes survey. Earlier this year it concluded that trust in politics was currently at its lowest point since the survey started measuring it in 19863.

This sounds pretty bad. Today 45% of people say they “almost never” trust government to place the needs of the nation above the interests of their party. That’s dramatically up from just 12% in 1986. And at the end other, people who say that they “just about always” trust the government has fallen from 40% to just 14%.

I’m not going to deny these numbers are bad – but I am sceptical that this is some urgent crisis that means we need to introduce all of these extra means of “participation”.

For example, here’s the same dataset, but as a rolling average over three years – which makes the data less of a migraine to look at.

Looking at this we can construct a story of rising distrust – starting in the late 80s/early 90s during the dregs of the Thatcher/Major governments. There was a brief uptick in trust during the early Blair years followed by a steady decline, and a big spike in distrust after the 2008 financial crisis. Then more recently, trust increased during the pandemic due to a “rally around the flag” effect, followed by a massive drop in trust in the Partygate/Truss years.

I’m sure that some of the decline in trust is deeply structural. The most important factor is probably that over the time period we all got internet connections. As I’ve written before – paranoid internet freaks are now a permanent feature of our politics, and it stands to reason that with fewer information gatekeepers, more people will consume alternative viewpoints/mad conspiracy theories.

But aside from the most recent few years, the chart also shows how trust scores have been relatively stable since the Coalition years. So could it just be that… the most recent government has been a bit shit?

This brings me back to the importance of material outcomes.

Looking at the line on the graph above, it strikes me that if we really want people to trust the government, it isn’t more “participatory policy making” that we need… but more delivery.

In other words, I think if we had a government that was making us feel richer – that was growing the economy and increasing real wages, and a government that was visibly building infrastructure and improving public services – it would of course increase trust in politics. People would be able to see that politicians aren’t just bullshitters – and that they’re actually changing lives.

And even though its unlikely that most voters will identify the specific causal through-line from policy to pay packet, if they feel like everything is working again and things are getting better, then that will implicitly legitimate the government and earn trust. If Labour deliver what they have promised by the next election (still a big question), I’ll be surprised if the trust score goes further down.

So if my more materialist theory of trust is right (feel free to argue in the comments), this has a big implication. It suggests that the answer to trust in government is not ‘more consultations’ as Demos propose, but functionally the opposite. The government shouldn’t spend its time hosting Citizens’ Assemblies. It should work out how to speed up existing government processes so that it can make decisions faster and actually start delivering.

If you enjoy nerdy politics, policy, tech and media takes, then subscribe (for free!) to get more direct to your inbox!

It still feels weird to refer to Labour as “the government”.

Even if you can convince the one Red Wall Brexit voter in the room that immigration is important, or the one Blue Wall NIMBY that building houses is necessary… how do you convey this to thousands, or millions of people who haven’t been through that process? I suppose the theory is that this deliberation informs policy makers of how to make the arguments, or how a given policy could be better shaped to meet the needs of specific demographics but I’m sceptical that you really need a big consultation to determine this.

Sidenote: I’m sure there was a CSV of the data somewhere, but I couldn’t find it. So I took a screenshot of the data-table in the PDF – which had been split and stacked up over two pages – and then asked ChatGPT to reassemble it into a CSV dataset and I watched as it wrote some Python code to recognise the characters and make sense of the data, automatically iterating several times to get the data in the right format. It was fucking incredible to witness.

Totally agree. I’m pretty sure Starmer promised he was going to give us a Government that would “tread more lightly” on our lives. That’s a good instinct. But getting his homework marked ad nauseam by panels of busybodies seems like the opposite of that. Just crack on, chaps! We’ve had 14 years of Tories and they’ve left a horrible mess. You don’t have time for this.

I think you’re spot on with the trust point. Possibly the single most pernicious aspect of having had Tory governments that were shit at delivery, even on their own terms (eg small boats), for 14 years is that lots of people have concluded that politicians of all stripes will not deliver. And the most pernicious aspect of the new media landscape is that players will shamelessly lie and say the government has not delivered even when it has. This is especially damaging with the over 60s, who often subsist in a specific corner that tells them black is white (immigration is a great example of this).

On your broader point, I have once seen deliberative decision-making done well and used to accelerate, rather than decelerate, transformative change. But it was at a relatively micro level: changing how stroke care was delivered in London. Stroke consultants were very skeptical about the changes at the outset, but the deliberative process helped get them on board, and it saved hundreds of lives every year. But it needed a very smart and aggressive team to do it — Tony Rudd, Ara Darzi, Ruth Carnall, Hannah Farrar, and others. And it wasn’t a truly public process, because the participants were all specialists.

https://www.england.nhs.uk/london/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/09/London-Stroke-Model.pdf