I have 2000 old VHS tapes in my garage and I don't know what to do with them

A story about data and a very foolish hobby

tl;dr: I have approximately 2000 VHS tapes containing off-air recordings of British TV in the last 90s and early 2000s in my garage. If you work for, or are connected with an archive that might be interested in taking them and saving the contents for posterity, I would love to talk to you. Please get in touch!

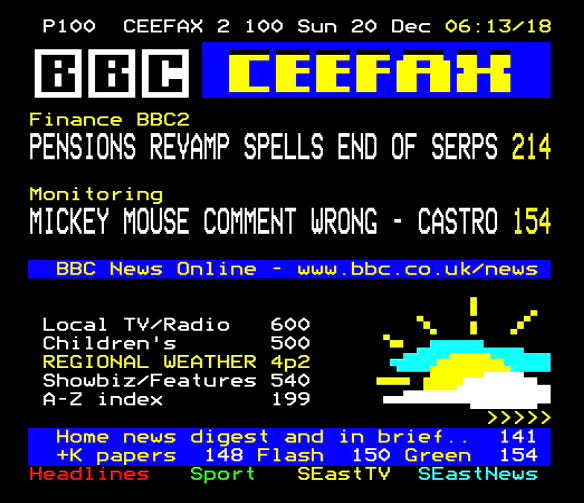

This week marks the 50th anniversary of a major technological milestone: The advent of teletext services in the UK, with the launch of Ceefax on the BBC1.

Until the mainstream adoption of the internet two decades later, teletext was an incredibly important source of news and information. Tens of millions of people used it on their TV every week – far more than read any newspapers or magazines at the time.

And in an era when papers only contained yesterday’s news and TV bulletins were just 30 minutes long, a few times a day, it was the closest thing we had to real time news.

I used to spend hours every week reading teletext. I grew up on the cusp of the internet era – but I remember how every night, with wifi not yet a thing, that I would scroll through virtually every page of Ceefax on the BBC, and Teletext on ITV and Channel 4, reading the news, the editorial features and even the proto-message-boards, in the form of Ceefax’s Backchat and Chatterbox pages.

And one of the most exciting days of my childhood was when my parents bought a TV with “fast text” – as it meant that I could finally play the Channel 4 quiz game Bamboozle.

My favourite thing on teletext though was the on-screen videogame magazine Digitiser, which was also on Channel 4. Created and mostly written by Paul Rose, it wasn’t like the rest of teletext, which was fairly dry in its presentation – Digi had an anarchic sense of humour, and exploited the medium to its full extent, with gags that made use of the “press reveal” button, and cartoon characters formed of blocks in the eight colours that the technology could handle.2

Even if you don’t remember these specific things though, if you’re British and over the age of 30 you probably remember using it. Because what’s striking looking back is how utterly ubiquitous teletext was – and yet today it has completely disappeared from our collective memory, like Avatar, Liz Truss and COVID-19.

This is where we get to some maddening digital history.

Obviously, teletext is not going to stick around for the internet era. But unlike newspapers and books published in the 1980s and 90s, which historians and nostalgic millennials can go back and rediscover, nobody thought to keep an archive of teletext.

This means there is no great vault containing the millions of words that were written by thousands of people, and read by tens of millions more. A Library of Alexandria’s worth of journalism and culture, some of the most widely read works of the 80s and 90s, have disappeared forever.

Teletext Ltd, which operated the ITV and Channel 4 services, is today a holiday website. It didn’t retain an archive of its pages, because why the hell would it?

But perhaps more surprisingly, beyond holding a few representative pages of what Ceefax used to be like, the BBC didn’t either3.

And in retrospect it seems like a bizarre omission. An act of cultural vandalism, akin to how the BBC famously destroyed recordings of Doctor Who, Dad’s Army and the like in the 1970s to save money.

It pains me in particularly that today that the fan-made archive of Digitiser, which was clearly very formative to me, is only about half complete.

But there is some good news for historians: There might just be a way to go back in time.

Press reveal

In 2011 something amazing happened.

A coder called Alistair Buxton discovered a box of old VHS tapes in his attic. And then he did something that I consider to be, essentially, witchcraft.

If you ever put a VHS tape recorded from the TV into your VCR, you may remember that hitting the “text” button didn’t show whatever teletext was on TV at the time of your recording – it was just a blank page.

That’s because of the way VHS tapes save data. VHS compresses the TV signal so that it fits on the tape in a similar way to how a JPEG doesn’t contain as much detailed picture information as a bitmap image. Instead of saving every pixel as it was in the original image, it saves only what it considers to be the most important elements to preserve a good enough facsimile of the original.

What Alistair realised though was that even though there were no complete teletext pages stored on his tapes, there were still fragments of teletext data captured and saved by the tapes.

So he wrote some code that does something mind-blowing. Using his software, if you play in a VHS tape to a TV capture card, it will take the raw recording data, pick out the nuggets of teletext, and like magic will stitch them back together into complete pages.

Like I say, it’s witchcraft.

For a couple of decades, we thought that great swathes of teletext had been destroyed forever. But with the application of some clever code, Alistair had essentially discovered a way to pull historic artefacts out of the ether, and save them for posterity.

Here’s an example of two recovered pages from one tape:

In the years since this breakthrough, a small community of heroes has emerged to save teletext using this method.

Numbering in the low-dozens, these brave nerds seek out VHS tape archives of off-air TV recordings, painstakingly capture the data and reassemble the pages. Conceivably, if the tapes are still out there and TV recordings can be found, it could be possible to rebuild teletext’s Library of Alexandria. Enough people out there, back in the day, were recording TV – it’s just a case of sourcing the right tapes, for the right days, and crunching through them to pick out the fragments of teletext.

And the work of doing so has already been underway for a number of years. Thanks to their efforts, today it is possible to browse through hundreds of historic teletext captures on The Teletext Archive, which is maintained by Jason Robertson, one of the most prolific teletext archaeologists.

And most importantly for me, as a result of the hard work, the Digitiser archive is slowly being rebuilt with new editions of the magazine getting rediscovered on a fairly regular basis.

My big teletext problem

This is where I come into the story, sort of.

I’ve been writing about teletext for over eight years now. I first wrote about teletext recovery in 2016. You can even hear me talk about teletext on this BBC podcast from 2020, where I tell something like the story above.

But then much like Olivia Nuzzi and RFK, or Owen Jones and Jeremy Corbyn, I got too close to my sources. But instead of this leading to an unwise romantic entanglement or almost destroying the Labour Party, it led to me trying to be a hero, and save teletext myself.

I saw on Twitter that a friend of mine was searching for a home for an incredible archive of around 2000 VHS tapes. Each contained around six hours of off-air recordings from British TV from the mid-90s to mid-2000s – as well as meticulous notes on the contents of each tape.

Apparently there were so many tapes because the original owner, a now elderly man, had made the recordings for his neighbour. Together they make for an incredible snapshot of TV from the time – everything from Blue Peter to Eurotrash.

Anyway, because the owner was getting on a bit, his son passed the tapes on to my friend – who had saved them from a trip to the dump. And now a few years on from that, my friend had decided that it was now time for him to offload them, so he could reclaim the space in his house.

That’s when I saw his tweet – and I immediately realised the teletext goldmine stored within. Unwittingly, this old guy might be a hero, who has accidentally saved a decade of teletext data from oblivion.

So I did the only logical thing I could do, and volunteered to take on the tapes. And that’s why today they take up around a quarter of the physical space in my garage.4

My thinking at the time was that this could be a new hobby – and an opportunity to do something good for the world, instead of spending all of my time doomscrolling on Twitter.

So I setup a desktop PC with the right hardware to support an ancient TV capture card and a relatively modern GPU. I installed Ubuntu and Alistair’s software. And I began to capture the tapes, saving both the video footage and the teletext data within.

And it was genuinely thrilling to see Alistair’s software at work.

As the first teletext data reemerged in front of me, it sent chills through me as I realised that I was the first person in two decades to see the contents, after it had been essentially lost forever.

I felt like an archaeologist, unravelling an ancient scroll that had been entombed in volcanic ash. But instead of containing previously untold bronze age epics, it containing music reviews, TV listings and Turner the Worm, from the early Blair era.

Seeing the old TV footage was great too, for a media nerd like me. The best bits were not the old episodes of Buffy the old guy had recorded – but seeing the stuff that would never have made it to DVD or streaming. The old adverts, the old trailers – and the old continuity. As a child of the 90s, it was very nostalgic to see ‘my’ era of Children’s BBC again, just as I remember it.

Here’s some CBBC continuity, featuring Simeon Courtie, an episode of Newsround with Chris Rogers, and a trailer for Live & Kicking that has aged *spectacularly* badly. You’ll have to watch to find out why.

However, it was only once I began capturing my enormous archive of tapes that I realised I had bitten off far more than I could chew.

Even though I had written some code of my own to try and speed up the capturing workflow, it quickly became apparent just how big the task ahead would be if I wanted to go through all 2000 tapes.

After around six months, I’d processed only maybe 40 tapes. And even worse for the project, my life was getting significantly busier again after a protracted pandemic social lull.

So for the past year or so, my VCR has remained on standby mode, the tapes in their boxes, gathering dust.

I need your help

I’ve reached a point where the tapes are just gnawing away at me too much.

When I look around my office and see the piles of unprocessed tapes, I feel a pang of anxiety in my stomach. My inaction is a disservice to our teletext forefathers. And when I see the brave face of my partner as she looks at the piles of VHS boxes in our garage, I just wonder if she is regretting the life choices that led to her living with me.

And it is deeply frustrating as someone who cares about this historic data too. I know I’ve got this rich, historic archive in my garage – potentially the only copies of thousands of teletext pages still in existence. And thanks to Alistair Buxton and the other teletext heroes building out the software, we have the means to save it.

But the one resource I don’t have is time.

And this is why, dear readers, I need your help.

I think now is the time to find a new home for this incredible archive of tapes.

I want them to go to an institution, organisation, or a person who will be able to give them the dedication they need to save the treasures within. The mild ticking clock is that VHS, as an analogue format, will deteriorate over time – so if the teletext data isn’t saved pretty soon, it could one day be too late.

I also want the archive to remain intact – to recognise the incredible contribution of the archive’s original accidental compiler.5

In terms of physical logistics: The tapes are located in my home, just outside of London, in Kent. And there are around 30 boxes – which take up quite a lot of physical space.

So here’s my ask: If you know someone who can take them, and either preserve the tapes as they are, or even better do the work of saving the teletext data and the video contents within, please get in touch with me. My contact details are on my “about” page.

I know there are data nerds, archivists and historians out there who care about stuff like this. Please do send this on to anyone you think might be able to help.

Alistair Buxton and the teletext recovery nerds have offered us a means to preserve this history before it is too late. If you’re someone out there who can help save it, now is the time to act!

If you’ve read this far in an article about teletext then you will definitely like my newsletter. Subscribe now (for free!) to get my takes on politics, policy, tech, and media direct to you inbox.

Confusingly, Teletext was also the name of ITV’s teletext service from 1993 (prior to that it was known as Oracle), but teletext is also the generic name for the technology.

In more recent years, Paul has revived Digi as a fun YouTube channel – which though a different medium and no longer about videogames, retains its distinct personality and humour.

Paul Rose has previously described how the way the computer system he used worked was that he’d often just write in the next day’s Digitiser over the top of the previous one – meaning that what was there previously wasn’t necessarily kept anywhere else as a separate file.

Yes, if you’re wondering, my partner is a saint.

I have his name, but I’m not naming him in this piece, as I’m not sure it is my place to do so.

If I were retired, I would take on this mission in a heartbeat. However, having meticulously digitised all the VHS tapes that I own (which you can count on two hands) I know what a time-consuming task it is. Granted, it could be argued that I didn't need to remove the cover of my VHS recorder and tweak the heads and tension for each individual cassette, but if you're going to archive something, you might as well aim for the best quality that you can achieve. I then spent hours upon hours slicing the recordings up in the correct places to extract each individual advert, link, programme etc. and also dating them. It was a lot of work, some of which can be seen here for anybody who's interested: https://www.youtube.com/@sphinx464/videos.

Of course, now that you've made me aware of the teletext data that could potentially be recovered from these tapes, I feel obliged to delve back into my archive. So, er, thanks... I guess!

Love this! I remember reading every word of Digitiser every day was excellent procrastination when I was supposed to be applying for games industry jobs.