The battle over pay-per-mile road tax could destroy Keir Starmer's government – here's how Labour can avoid disaster

The new culture war to end all culture wars?

POD! A blockbuster episode of The Abundance Agenda this week. Martin shares his massive scoop, about HS2’s ‘Bridge to Nowhere’ that is worse than the bat tunnel. I’m talking digital traffic orders. And then we check in with Lord Ben Gascoigne who is chairing a House of Lords inquiry into how to build New Towns. Check it out!

It’s finally happening!

According to the Telegraph, Rachel Reeves is planning to announce a major change to road taxes, where electric cars will have to pay taxes on a per-mile basis, on top of existing road taxes. The plan is reportedly to introduce the scheme in 2028 and have motorists pay around three pence per mile.

In my view, this is great news, as it’s about time. I’ve written before about how we’re going to have to make this change. And as I’m on holiday this week, I thought I’d share an updated version of that take below, because though the move is an impressively bold one from a government that often seems afraid of its own tail, it is not without political risk.1

In fact, we can already see signs of how it will land. The Telegraph quotes the response from Mel Stride, Reeves’s shadow, as saying “If you own it, Labour will tax it”.

And though plans only apply to electric cars, the risk of wider backlash is obvious, as everyone is slowly going electric. Pay-per-mile will simply be how the system works in the future, so it’ll be interesting to see whether GB News and your dad’s Facebook feed come down on the side of this being the woke EV drivers finally paying their fair share – or a sign of the Orwellian, digital ID, 15-minute cities nightmare to come.

Anyway, as pay-per-mile is finally happening, let’s dig in and figure out why it is so necessary, why it is a massive political landmine for the government, and what can be done to mitigate the political damage now that Rachel Reeves appears to be about step on it.

If you enjoy nerdy politics and policy takes, then subscribe (for free!) to get more like this directly in your inbox.

Why a motoring tax nightmare is unavoidable

So what’s the policy problem that has caused this? Essentially, it turns out that the excellent progress we’ve made transitioning to electric vehicles (EVs) is great for the climate, but less good for the government’s future tax revenues.

As things stand today, motorists pay two main taxes: Vehicle Excise Duty (VED) and fuel duty – what we tend to just call road tax and petrol tax. VED currently raises the government around £8.4bn every year – and as of this year, EV owners are no longer exempt. So if have an electric car, there’s a standard rate of £195 to fork over – or even more if your vehicle is particularly fancy.

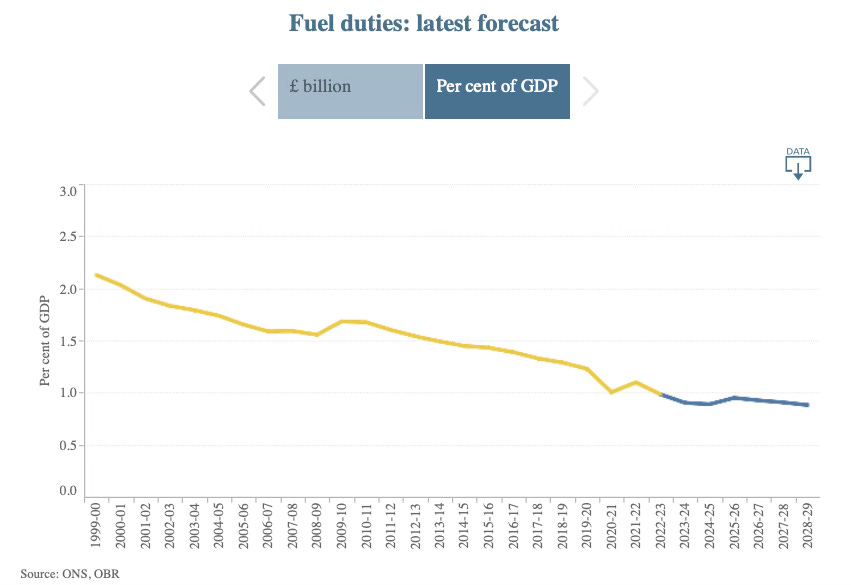

The real problem, then, is fuel duty, which accounts for 2% of the government’s total tax take, which according to the OBR will this year be around £24.4bn. (It used to even higher, until fuel duty was cut following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.)

So the problem is obvious: electric vehicles don’t use petrol. So as a source of revenue, the Treasury is increasingly screwed here. To put the figure in context, it is far from a trivial sum. £24.4bn is enough money to pay for basically all of the railways, or the entire social care system.

So in the not-too-distant future, unless the government changes how we tax motoring, there’s going to be an enormous black hole in the government’s finances where fuel duty should have been.

And what makes this a problem for Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves specifically is two important facts about it.

First, this is not some hypothetical, distant future problem, as the electric car transition is already well underway. According to the most recent figures, EVs account for 25.4% of new vehicle sales – or just over 50% if you include hybrids. And this share is increasing every year.

And whether the ban on new fossil-fuelled cars is 2030, 2035, or even if the time limit were to be removed altogether, it doesn’t really matter. Because the rest of the world and the car industry is now irreversibly going electric. Even if an EV is currently out of your price range today, it is likely that your next car will be electric2.

So unless the motoring tax system is changed, car and fuel tax revenues are going to continue to plummet during this Parliament. In fact, according to the House of Commons Transport Committee, revenues from motoring taxes could hit zero by 2040 – so by 2034, at the end of Starmer’s hoped-for ‘decade of renewal’, revenues will be dramatically lower than they are now.

In other words, the government won’t be able to avoid dealing with the consequences of this.

And this brings me to the second reason this is a political problem: doing anything to fix vehicle and fuel taxes is going to be utterly toxic, compared to almost everything else – even digital ID3.

Road pricing is the only option

Given that we know there’s this huge problem, the obvious question is what to do about it.

One option would be to simply let motoring taxes fall to zero, and increase other taxes to compensate. According to that same Transport Committee report, that would be roughly equivalent to putting an extra five pence on income tax. So even if Reeves does (as seems clear now) raise taxes, she’d still have to be clinically insane to propose this alternative to the electorate.

It’s safe to say, then, that the tax burden should still fall on the motorists doing the driving. Not only is this the path of least resistance as they already pay tax to own and drive a car, but it is also a good thing in and of itself: We should want driving to carry at least some costs, as though there are no emissions from EVs, there are still other negative externalities, like traffic congestion and needing to have ugly, sprawling car parks across the country. So we should want public transport and other alternatives to remain at least as attractive as they are now – dropping motoring taxes would shift this in the wrong direction.

But exactly how to administer such a tax is tricky. One Treasury official called fuel duty a “perfect” tax, as it is paid mostly by the people who use the most petrol – with those who drive more, or drive the most gas-guzzling cars, paying the most.

Unfortunately, however, there is no similarly ‘perfect’ EV equivalent. It isn’t really possible to do something clever like tax the electricity used to charge the batteries in electric cars, because most people charge at home, and there isn’t an easy or obvious way to separate out EV charging from other domestic energy usage.

So this is why there’s a pretty broad expert consensus that the only viable option in the future is going to be some form of road pricing, where we do away with fuel duty, and instead motorists pay based on the roads they use and/or how much driving they actually do – Reeves has reportedly chosen the latter.

Conceptually, I think this makes a lot of sense, as it means the people who do the most driving pay the most tax.

But the problem for Labour is that politically it’s hard to think of anything worse, short of obliging every nursery to employ an XL Bully dog to supervise the children.

The political nightmare

The reason why it would be politically challenging to pitch road pricing to the electorate seems almost self-evidently obvious to me, but it is worth digging into a little, because like so many good ideas originated by experts, it might be the best way to design something on paper, but the politics of such an idea seem a little under-considered.

For example, that Transport Committee report has lots to say on the technical implementation of a road pricing system, but rather less to say on how politicians might be able to get away with rolling out such a system without losing their seats. Instead, it simply recommends that the government “must start an honest conversation with the public” on the policy. Good luck with that.

Once you consider the politics, it’s clear just how politically tricky pay-per-mile will be for whoever is in Downing Street, because the problems begin at first principles, as any new tax system will necessarily create winners and losers.

For example, even if the new system is calibrated to collect the same amount of money in total,4 it is just inevitable that a non-trivial number of people will end up paying more under the new system, because of the differing methodology by which the tax is calculated.

This means that however the new tax is sliced, there will be a non-trivial number of grumpy people – who will make for a readily available supply of people for journalists to interview and for Question Time to put in the audience. And no doubt many ‘losers’ will have broadly sympathetic stories that defy the design of the system, even if the new rules are set to allow exceptions and workarounds for some specific circumstances5.

And more substantively, all of the ‘losers’ will continue to have one vote each, and will be allowed to vote at the next election.

This makes it especially difficult to change the system, as we know from basically all recent history how politicians are particularly (and not unjustifiably) scared of motorists as a class of voters. That’s why fuel duty hasn’t been increased since 2011, with Chancellors deferring the opportunity to raise it in line with inflation at every budget since.

Similarly, the experience of London’s Ultra-Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ) rollout shows the political toxicity of motoring taxes. On one level, this was because, even though only a tiny proportion of vehicles were affected, many more motorists feared they would be caught out by the new charges. And though some polls claim that now it is in place ULEZ is popular, you can’t deny that Sadiq Khan took political damage over its implementation.

In any case, I think ULEZ is also instructive more broadly about the psychology of pay-per-mile. Any new road pricing system, like ULEZ, will necessarily involve a monthly or yearly statement where money exits your bank account like an unwelcome fee. I think this is different from buying petrol, where it feels more like you’re buying a product (ie: petrol) rather than being penalised, as the tax is ‘invisibly’ baked into the price. So even if the system is designed so that most people don’t end up paying more, it’s still added psychological friction for literally every motorist in the country.

So this is all to say that changing the way motoring taxes work makes for one hell of a dangerous minefield.

That’s why I think it’s pretty easy to imagine how, in 2029 or whenever, once the Tories decide they want to start winning elections again, this could be the issue that propels the new, fresh-faced Conservative leader of the opposition, Malala Yousafzai,6 into the ascendancy. If she can weaponise the issue and appear more on the side of drivers, then it could be the potent issue that makes her party credible again7, if Nigel Farage doesn’t beat her to it first.

And there are already examples of road pricing being weaponised like this. During the last London mayoral election, Tory candidate Susan Hall (remember her?) claimed Sadiq Khan was planning to introduce such a system8. And also last year, former Transport Secretary Mark Harper claimed (rightly, I guess) that Keir Starmer would introduce road pricing too.

Selling road pricing

So given this seemingly politically impossible situation on the horizon, how can the Labour government get away with introducing pay-per-mile, without destroying its majority in the process?

Here, I think a good starting point actually comes from the right-wing Policy Exchange think tank. A couple of years ago, it published a paper called A New Deal For Drivers, which outlined six principles any new road pricing system should adhere to, in order to win the approval of the electorate:

No net additional costs to drivers on average i.e., revenue neutral compared to current total fuel duty and Vehicle Excise Duty;

Most drivers should pay less under road pricing than they paid in fuel duty and road tax; in particular rural drivers and those in ‘left behind’ areas must pay less;

The scheme must not rely on a shift to public transport or other transport modes;

Nearly all drivers will be better off overall given the benefits of free traffic flow—all or nearly all drivers will experience faster roads;

Improved safety of modern cars means that the Government should commission a study to assess whether speed limits on motorways can be safely raised to 80 mph;

More of the budget should be shifted towards road improvements, road building, and infrastructure such as bridges and tunnels.

I think most of these are pretty sensible suggestions. Making it revenue neutral will make sure the reforms aren’t framed as a cash grab by the government.9

And as tempting as it might be to urbanist-minded people, who like trains and buses (people like me), the Labour government must do everything it can to not make it appear as though any public transport scheme/low-traffic-neighbourhood/etc is tied to the launch of the new tax regime, otherwise there is a ready made attack of “Labour hates car owners and wants to tax you out of your car”.

I’m less convinced by the idea of raising speed limits on the motorway – but we can argue about that on the merits when the debate happens.

However, I do think that sixth point is important: When announcing the new road pricing system, Reeves should pair it with a Rishi-at-Tory-conference-style giveaway, dishing out road upgrades, pothole fixes and new bypasses to as many marginal constituencies as possible.

Then in terms of my own less well-evidenced ideas, I think if I were designing the transition to the new system for everyone (the inevitable next step), I’d plan for a long transition and make the system opt-in for fossil-fuelled drivers10 – so that motorists can choose to stick with the existing system, or switch over to a road pricing system. And then I’d make the road pricing system work out slightly cheaper for most drivers, so that there is a natural incentive to make the switch11. That’s slightly less money for the Treasury in the short term – but “less” is more than “zero”, and this is about making the best of a difficult transition.

And as for the underlying technology, there are several ways of doing it. Reeves is reportedly going for the most straightforward option of basically comparing the odometer on a year-by-year basis to work out how far the car has driven. But this raises questions about enforcement – it definitely creates a stronger incentive for people to cheat the system.

However, there are conceivable technological means of enforcement. I would definitely not use any roadside infrastructure like ULEZ-style cameras, because of the inevitable backlash over surveillance, not to mention the cost of maintenance. But I think there could be an opportunity to let motorists hook up their car’s on-board computer, or a separate hardware device fitted to the car, to monitor usage. Perhaps there could be an incentive where if you let your insurer monitor your driving in real time, you get a slight discount, as your tax owed will be verifiable?12

Stepping over the landmine

Ultimately, then, I think this is definitely the right move to make. There will definitely be political pain – the only choice the government has is when it should inflict it on itself.

And now is almost certainly the right time. Even though the government faces challenges on many fronts, and everyone seems pretty miserable about its prospects, we’re currently in what my friend Michael Dnes from Stonehaven calls the ‘electric window’. The number of electric vehicles on the road will never again be as low as they are now, meaning that the longer the government waits to act, the more political pain there will be.

So here’s hoping that now the story has been reported, the government follows through with the plans, and doesn’t chicken out before Budget Day.

Like politics and policy takes? Or nerdy transport and infrastructure stuff? Then you’ll like my newsletter. Sign up (for free!) to get it in your inbox.

Don’t worry, I’ll have a fun guest post tomorrow, and maybe something new from me in a few days!

I can’t yet afford to replace my knackered diesel with an EV – but I think it’s likely prices on the second hand market are going to plummet in the next few years, now that we’re solidly on the steep part of S-curve, and as EV early adopters start to upgrade their cars in the next few years.

I honestly think at this point switching to road pricing would be an even worse political issue for an incumbent government than rejoining the Single Market.

As far as I can tell from the reporting, the pay-per-mile will be on top of existing VED. It’s unclear whether this will just be higher taxes, or if base VED will be reduced.

So you can imagine how even if the government were to exempt (spins wheels) community groups running buses to take vulnerable people to hospital appointments, there will still be someone who uses a private car to visit relatives in long term care, who still feel aggrieved.

Elected in a by-election after Robert Jenrick resigns his seat to become a TikTok influencer.

It’s true that many road schemes later become popular or at least accepted, like most Londoners are now completely fine with the Congestion Charge. But being popular many years later isn’t very helpful if the political problem is the damage from creating it in the first place.

If Sadiq Khan has had to repeatedly distance himself from the idea because of its electoral toxicity in London, it illustrates how utterly toxic it will be in the rest of the country where the proportion of car owners is even higher.

Obviously grabbing some cash is something that Reeves needs to do with the budget. But if I were her, I’d make the conceptual change to the road tax system now, and worry about using it to raise cash later.

Though I think you could force EV-owners on to the new system, so that when people eventually upgrade to an EV of their own accord, they are just migrated on to the new road charging system. And much like the EV transition more generally, the government could also more easily oblige companies and organisations with lorries and fleet vehicles to switch over, without suffering the direct political pain of forcing individuals to change.

I think it could work a bit like smart-meters, where there will always be a core of maniacs who don’t want to change, while most other people will find the prospect of saving money more attractive.

Amusingly this idea I’ve just invented in my head is conceptually similar to GOV.UK Verify, a disastrous government programme to create a decentralised login system by using companies like banks and mobile phone companies to verify digital identities, without the need for a centralised digital ID system.

One core problem with this plan is that we are desperately trying to incentivise purchase of new EVs (through giving everyone who buys one a bung of £3750), and at the same time disincentivising ownership (through the imposition of VED) and use (through road-pricing).

It also overlooks that the electricity put into EV is already taxed: at 5% if at home and 20% at a roadside charger. It is eminently possible for these charges to increase to replace fuel duty.

Nearly all charging at home is done using smart chargers which can distinguish EV charging from say boiling the kettle. And those early chargers which don’t have this capability will need replacing soon. It would be simple to increase the VAT on this element of home electricity use to the (absurd) level of 55% of petrol costs which is made up of tax. It would, however continue to run counter to the government’s stated aim of decarbonisation and would disincentivise use of home micro-generation and storage.

One enforcement option: your MOT.

Garages already have to send paperwork off as a part of the MOT process, why not incorporate sending odometer readings as a part of the process? You’ve got a defined time period (annually between MOTs), a price-per-mile (truppence), and a third-party agent available (mechanic).

Unless there’s going to be a radical change to the MOT system, there shouldn’t really be a need for all sorts of wizardry to implement road-pricing.