TfL's AI Tube Station experiment is amazing and slightly terrifying

Mind the Orwellian Surveillance Apparatus

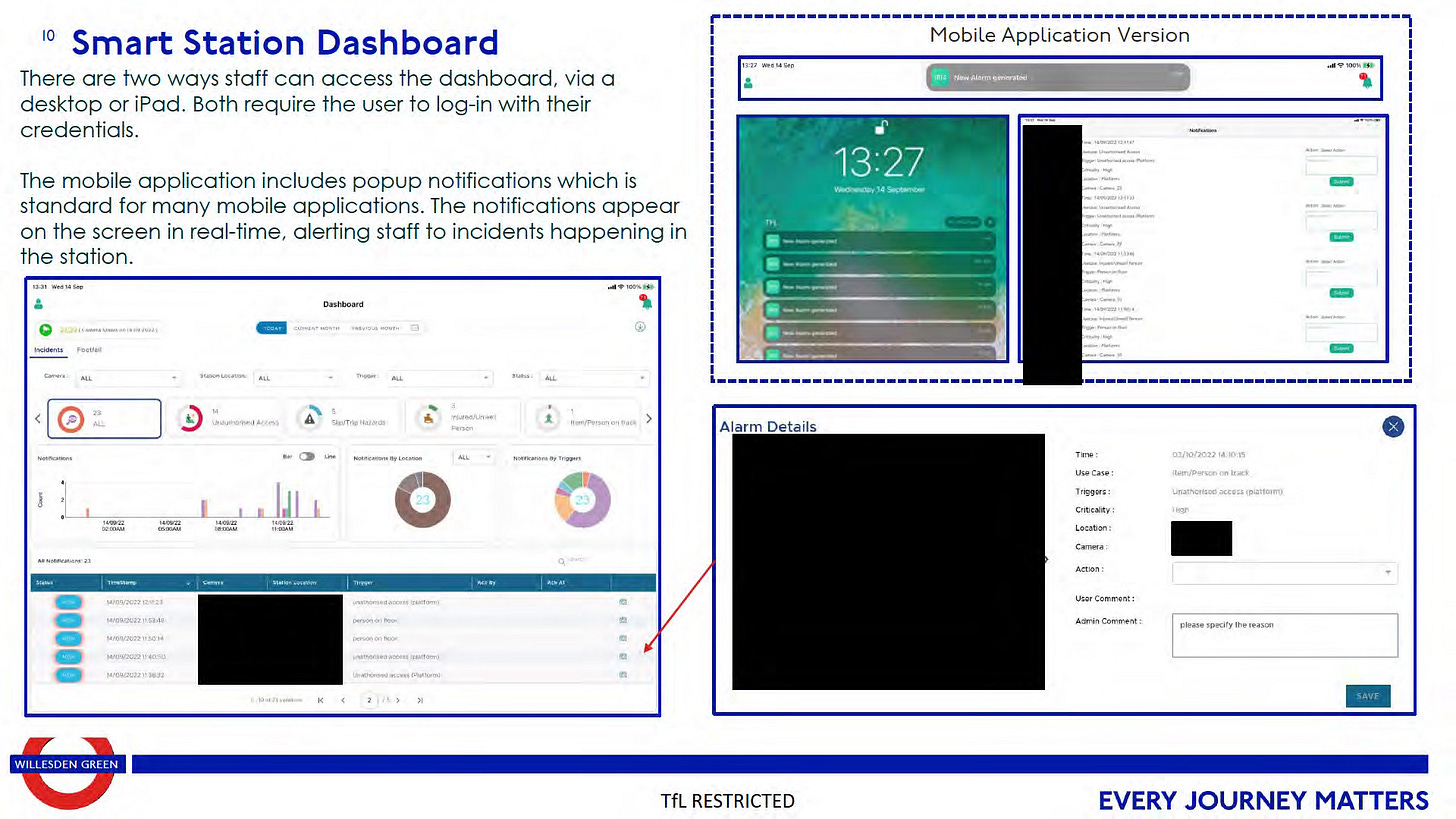

If you want a vivid illustration of just how transformative Artificial Intelligence (AI) is, and how quickly it has already changed the world, look at this xkcd cartoon posted just ten years ago1.

When it was posted, it was – as the cartoon says – virtually impossible for a computer to analyse the contents of images reliably. The idea that we could write software to recognise objects in photos was pretty much science fiction. But a decade on, this sort of image recognition technology is ubiquitous.

AI – the name we’ve landed on for this capability – is why you can type “dog” into the search box on a modern smartphone, and have it return every picture you’ve ever taken of a dog. It’s why Apple’s new “Vision Pro” headset can be controlled by simply waving your hands in the air in front of you. And it’s why self-driving vehicles are no longer an impossible fantasy, but are already being tested on real roads in trials around the world.

However, we’re still only in the very early days of the AI era, and that’s mostly the big tech firms building AI-powered features into their products. But what’s more interesting about the technology is that now the breakthrough has been made, AI has essentially been commoditised. It isn’t just the likes of Apple and Google that get to use AI – pretty much anyone can.

And this brings me to Transport for London (TfL) and the London Underground.

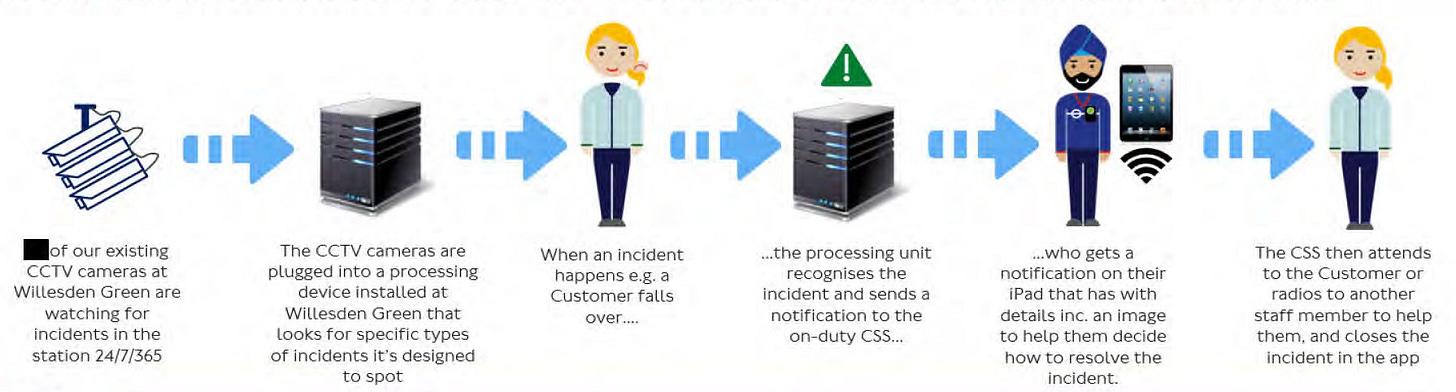

At the end of last year, it was widely reported that the transit agency had launched an intriguing trial at Willesden Green station in North West London. The idea seemed to be that AI cameras would be used to spot people jumping or pushing their way through ticket barriers, to fight back against fare evasion.

The reporting at the time was not especially detailed – with only vague nods to how the software works, or what it would be capable of. As it turns out, the trial was so much more than this.

That’s why I’m delighted today to bring you the full, jaw-dropping story of TfL’s Willesden AI trial. Thanks to the Freedom of Information Act, I’ve obtained a number of documents that reveal the full extent of what the trial was trying to achieve – and what TfL was able to learn by putting it into practice2.

And the results are both amazing and, frankly, a little scary.

So read on to find out more.

Subscribe now (for free!) to get more politics, policy, tech, media, and crucially transport takes direct to your inbox.

Introducing the ‘smart’ tube station

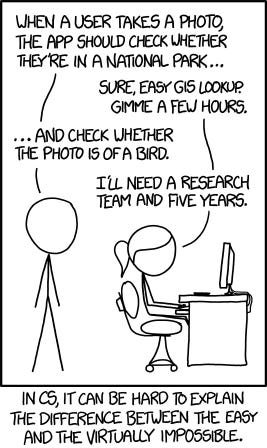

The experiment began in October 2022 and ran until the end of September last year. Willesden Green was selected specifically because it was the sort of station that could benefit from an extra pair of eyes3: It’s classed as a small “local” station, and it does not have step-free access. The reason why this matters will soon become clear.

To make the station “smart”, what TfL did was essentially install some extra hardware and software in the control room4 to monitor the existing analogue CCTV cameras.

This is where things start to get mind-blowing. Because this was not just about spotting fare evaders. The trial wasn’t a couple of special cameras monitoring the ticket gate-line in the station. It was AI being applied to every camera in the building. And it was about using the cameras to spot dozens of different things that might happen inside the station.

For example, if a passenger falls over on the platform, the AI will spot them on the ground. This will then trigger a notification on the iPads used by station staff, so that they can then run over and help them back up. Or if the AI spots someone standing close to the platform edge, looking like they are planning to jump, it will alert staff to intervene before it is too late.

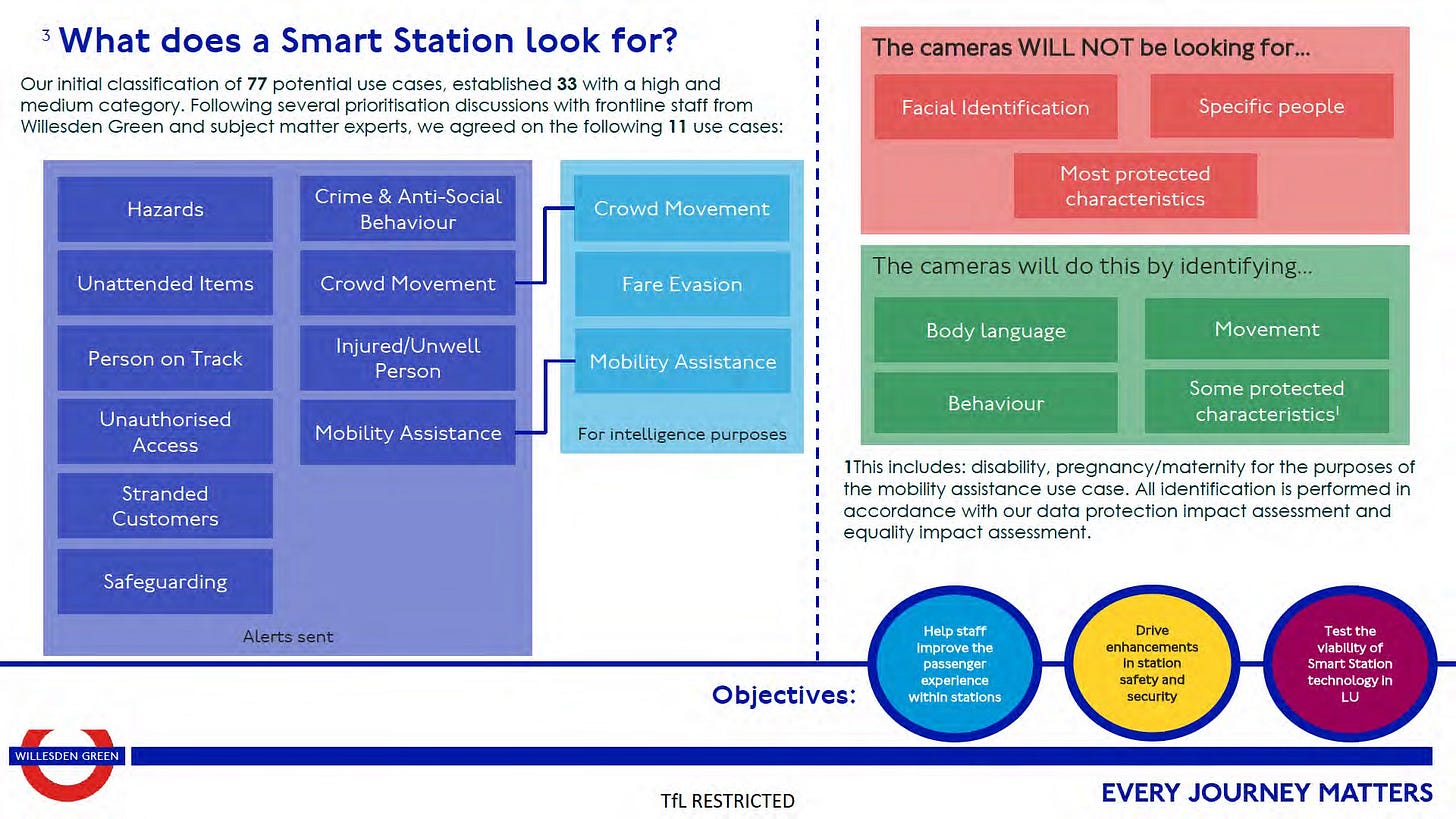

In total, the system could apparently identify up to 77 different ‘use cases’ – though only eleven were used during trial. This ranges from significant incidents, like fare evasion, crime and anti-social behaviour, all the way down to more trivial matters, like spilled drinks or even discarded newspapers.

Here’s the key slide, which reveals the full extent of what the system is capable of:

It’s very easy to imagine how powerful this could be. If someone steps foot on to the tracks5, or into an unauthorised areas of the station, the staff will receive an immediate alert. That improves security. If someone appears to be ill, the staff will quickly know about it too. That improves passenger welfare.

And if someone in a wheelchair passes through the station, they can be immediately flagged to staff, so that any assistance they need can be provided – which could be particularly important at a station like Willesden Green, where there isn’t any step-free access.

From a management perspective, the system could also be a powerful tool for collecting statistical data. For example, it can track how crowds move through stations, which could be useful for managing capacity at rush hour or knowing where to deploy staff when there’s a football crowd passing through.

What’s amazing about this is that it provides an amazingly granular level of detail over what is happening at the station – and that it’s only possible because AI computer vision essentially changes what used to be static images into a series of legible digital building blocks that logic can be applied to.

For example, in the “safeguarding” bucket of use-cases, the AI was programmed to alert staff if a person was sat on a bench for longer than ten minutes or if they were in the ticket hall for longer than 15 minutes, as it implies they may be lost or require help.

And if someone is stood over the yellow line on the platform edge for more than 30 seconds, it similarly sends an alert, which prompts the staff to make a tannoy announcement warning passengers to stand back. (There were apparently 2194 alerts like this sent during the trial period – that’s a lot of little incremental safety nudges.)

Spotting bad behaviour

Helping people is one thing, but the system is also capable of spotting different sorts of bad behaviour too.

For example, if someone passes through the station with a weapon, the AI is apparently capable of spotting it. In fact, to train the system, TfL says it worked with a British Transport Police firearms officer, who moved around the station while wielding a machete and a handgun, to teach the cameras what they look like.

During the trial period there were apparently six ‘real’ weapons alerts. Though it’s not clear whether or not they were false positives, amusingly that’s more than the 4 alerts for smoking or vaping in the station.6

My favourite thing from the TfL docs though is on the attempts by the AI to spot “aggressive behaviour”. Unfortunately for reasons TfL redacted from the documents, there was insufficient training data to make this reliable (what would this even look like?).

So TfL hit upon a novel solution: They instead trained the system to spot people with both arms raised in the air – because this is thought to be a “common behaviour” linked to acts of aggression (presumably raised fists or ‘hands up’ as a surrender-like gesture).

Happily there weren’t any ‘real’ aggressive incidents during the trial – but I’d guess a few false positives (like the guy hanging up the poster in the left screen-cap) isn’t the worst thing when you want to alert staff that something might be going down inside the station.

And there is one other added benefit to the “hands raised” trick: It also adds an extra layer of security for staff. It means that if they are faced with someone behaving violently, and are unable to reach their radio to call for help, the staff themselves can simply raise their arms to trigger an alert to their colleagues.

Fare evasion

And finally, fare evasion – which was, after all, the reason TfL said that it wanted to try the technology in the first place.

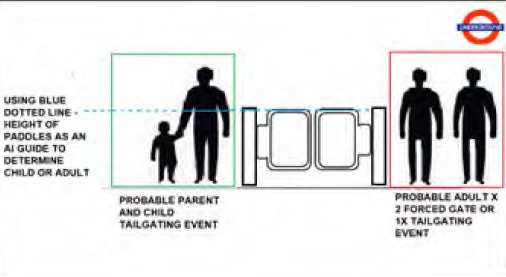

To make it possible for the cameras to spot people jumping the barriers, crawling under the barriers (!), or ‘tailgating’ – when multiple people pass through at the same time – TfL manually scrubbed through and tagged “several hours” of CCTV footage to train the system to teach it what fare evasion looks like.

And it appears the system got pretty good at spotting it.

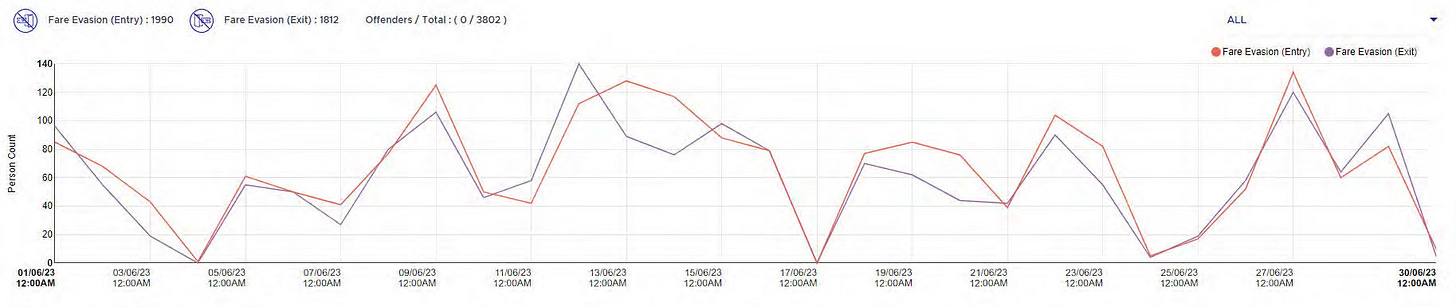

Here’s one chart showing 3802 fare evasion alerts over the course of June 2023 – there were over 26,000 during eleven months of the trial in total7.

Amusingly, to make detections more accurate, TfL had to go back and reconfigure it to avoid counting kids as fare evaders – and they did it by automatically disregarding anyone shorter than the ticket gates.

So TfL can seemingly identify fare evaders, but the agency also learned that stopping them may be harder. For a start, during the trial staff were not sent fare evasion alerts on their iPads deliberately. This was because (after discussions with the trade union) it was decided that it could put staff in a dangerous position if they’re supposed to confront, say, someone who just jumped a barrier.

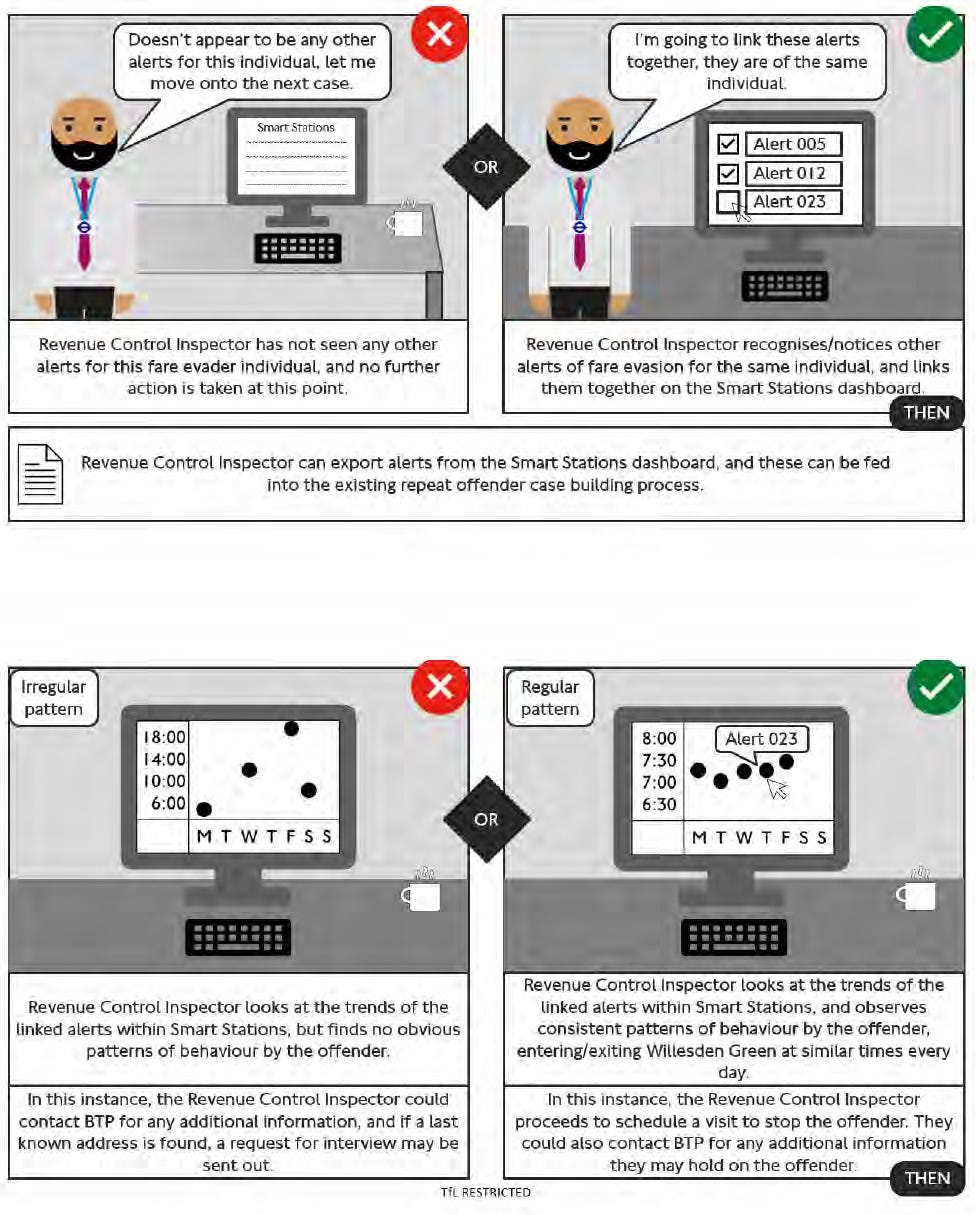

But the bigger problem was, well, identifying suspected evaders. When the trial first started, all faces were automatically blurred to maintain passenger privacy – but when it moved on to phase 2, an exception was made for fare evasion.

This meant that the AI could feed into what was previously a manual process which would rely on station staff recognising repeat offenders, and then filing a manual report to TfL’s revenue enforcement team.

With AI however, this process can be automated, but only to an extent. The documents explain that recognised faces are manually double-checked for matches. Once they have been identified, TfL’s Revenue Control team then need to manually put together a case against the evader.

According to the above diagram, Revenue Control will try to determine patterns of behaviour when there is a persistent evader – and if they’re turning up to the station and skipping through in a reliable pattern, the inspectors will turn up at the station to ambush them – and then present them with all of the evidence against them.

However, exactly how helpful AI is here remains to be seen, as the report says that “The process was successfully tested and although we did not see the results we had hoped, we also ran out of time.”8

The new normal

So this, in a nutshell, is what TfL has been testing. It’s a striking example of how AI can be operationalised to increase productivity, improve safety and provide managers with more insights.

And if I were TfL looking at the results, I’d think it was so utterly obvious how useful the AI cameras are – I’d want to deploy the technology widely.

Imagine if every camera in every Tube station had the same capabilities. It would undoubtedly make stations function much more effectively, as staff would more quickly attend to those in need, whether they are experiencing a serious medical incident or are just a confused tourist wanting to know why Abbey Road station isn’t actually home to the famous Beatles crossing9.

When reading the TfL docs, I kept imagining how this same technology will be used in the not too distant future. For example, imagine staff equipped not with iPads, but with an Apple Vision Pro headset. Serious alerts would not just set off a beeping noise in a jacket pocket, but the notification would appear in vision, like the Terminator’s heads-up display, along with a live video feed showing what was happening.

On a more boring level, there are tonnes of opportunities for incremental gains. It could be possible for augmented reality software to guide cleaning and maintenance staff to the spill that needs mopping up or the lightbulb that needs changing. Or when you plan a journey on Google Maps, it could warn you to avoid changing at Stratford to avoid the West Ham fans upset after a six-nil loss10. The entire travel experience could just be made that little bit more pleasant in a dozen little ways11.

And with my “fan of competent administration” hat on12, on a zoomed-out macro-level, data collected by the AI could be incredible for planning. Need to build a business case to install a lift? Now you can get an exact count of the number of people passing through with wheelchairs, prams and over-sized luggage. Want to raise cleanliness standards across the network? Then it would be easy to generate a ranked list of the muckiest stations based on visible litter.

In other words, the possibilities for improvements to almost every aspect of operating an underground railway network are huge.

And hell, there’s no technical reason why TfL couldn’t build a ticketing system that removes ticket barriers entirely – and instead uses facial recognition to link your face to your payment card – massively reducing friction when using the Tube network.

But this all said, I must admit there are huge nagging doubts in my mind about the whole thing too.

Much like when I wrote about how TfL use aggregated mobile data to figure out how people are moving around London, I can’t help but feel uneasy about the Orwellian implications of AI cameras watching our every move.

Until machine learning was invented, using CCTV data was still a hassle for the authorities that operate it – a human operator would have to manually comb through it to pick out anything important.

But with AI, what used to be abstract arrays of different coloured pixels can now be easily turned into meaningful data – and our movements, our body language and what we’re wearing are just metadata that can be mined by the authorities for good and for ill.

And to be fair, this Orwellian oversight could be a good thing. Literally over the last few weeks, we’ve witnessed a huge manhunt for a guy suspected of being involved in a chemical attack. At the time of writing, he was last seen on the Victoria Line. So if this AI technology had already been rolled out across the Tube network, it could have conceivably been possible to find him before he had even left the station.

But what makes the tech powerful is also what makes it scary. It would be trivial from a software (if not legal) perspective to train the cameras to identify, say, Israeli or Palestinian flags – or any other symbol you don’t like. The system could be used to surveil staff, and work them even harder, by literally keeping a by-the-second count of their idle time while on shift. And of course, the black-box AI training data could turn out the be flawed, perhaps unfairly or disproportionately identifying fare evaders with certain skin colours.

Very quickly, the downstream civil liberties implications of the technology become potentially… not great.

So once again, I’m ending a piece about TfL’s data hoarding with an unsatisfying ending, as I don’t really know how I feel about this. (Let me know in the comments what you think.)

But perhaps more importantly, what I think doesn’t matter. The time since that XKCD cartoon teaches us something important. That this technology is here now, and it is already everywhere. All of the positive aspects of the technology apply equally to everything from shopping centres and supermarkets to stadiums and airports13. It’s inevitable that it will be used everywhere.

So this is just a thing that exists in the world now. And even if we wanted to stop it being used, to do so would be just as virtually impossible as inventing it felt in the first place.

Phew! You reached the end! Subscribe now (for free!) to get more politics, policy, tech, media and transport takes direct to your inbox.

And if you really enjoyed it, please do take out a premium subscription to support my work and help me write every single week.

And please do share this with your friends and followers as the graph pointing upwards makes me feel happy.

Oh, and don’t forget to follow me on Twitter and… BlueSky, where I may one day start posting properly.

I’m stealing this example from the excellent Tom Chivers, who tweeted the cartoon a few weeks ago to illustrate the same point.

In between writing this piece and its publication, I was absolutely furious to see that Wired had published a piece based on these docs before me. It looks like TfL responded to both of our FOI requests on the same day, and, alas, Wired smartly didn’t think “I’ll save this for Monday as I’ve already published something this week.”. Anyway, I’m still furious though, not least because annoying TfL with FOI requests is my schtick.

A station on the Jubilee Line was specifically sought, because the internal project sponsor inside TfL was the guy who is in charge of customer service on the Jubilee Line. Politics!

Interesting nerd note: All of the processing appears to have happened locally on site, using a machine with a couple of GPUs inside of it – no cloud upload required.

One of the maddest things I’ve ever seen on the Tube was at Mile End station, when someone on the platform on the other side dropped their wallet on to the tracks. So they just… casually jumped down and grabbed it, before jumping back up. It was over before my brain kicked into gear and realised what was happening – but just seconds later could have been deadly.

Something that makes me a bit sceptical of the trial is that… this training apparently worked? Similarly, to train the system on passengers having fallen off, the report suggests staff simulated falling down the steps and lying the ground to test the image recognition. My assumption would have been that significantly more training data would be needed – but TfL’s report says they were “happy” with the results – especially given the relatively poor quality of the ageing CCTV cameras.

Willesden Green had 5.35m passengers in 2022, which by my back of the envelope calculation means that about 0.5% of people travel through the station are skipping the barriers.

It isn’t clear from the docs as the reason is redacted, but it appears that staff on the ground struggled to fill enough anti-social behaviour forms to build any cases against offenders.

In fact, about six months ago when I wrote an incendiary piece arguing that we should aim to close all of the train station ticket offices, I made a throwaway suggestion if railway companies wanted to go crazy, they could use AI to spot wheelchair users who require assistance and send a notification. Little did I know that the technology already exists and TfL was already using it.

I can’t quite believe I’m making a topical football reference either.

Though one thing I think TfL does extremely well compared to other places is in terms of how clean London transport feels. You rarely see graffiti on trains here, whereas it’s almost part of the look of trains in other cities.

It’s a top hat, obviously.

I’d be astonished if it isn’t already being used in airports.

I sometimes use a wheelchair and would appreciate the extra efficiency of getting help without having to find or be seen by staff. It would also be good if the AI could be trained to spot broken lifts (e.g. if no-one used it for an unusual number of hours) which are a nightmare when one being broken means the station is totally inaccessible, and TfL shared that information with the likes of Google Maps. AI is not going anywhere and the benefits are so strong it seems obvious to implement this, refine the use cases and training over time, whilst ensuring reasonable protections remain to protect privacy etc. A fascinating read, but I am disappointed the PAF was not mentioned.

I've often wanted this in Morrisons: for the cameras to detect that there's a customer repeatedly circling the same 3 aisles, scanning the shelves and getting steadily more agitated, then send a member of staff over to ask what it is that I can't find.

Though if the system could predict the specific item that I was looking for, that'd probably be going too far …