It's crazy how much Transport for London can learn about us from our mobile data

Big Brother meets Big Data

Hey, listen! Make sure you head over to What’s Happening Now, where you can hear a special podcast interview I recorded with Richard Sambrook, former director of BBC News and the World Service. We discussed how stories are prioritised, how to navigate tricky editorial decisions around balance and fairness, and the future of the BBC. If you’re at all interested in media stuff (I know you are), then I think you’re going to enjoy it. Listen here (or search for What’s Happening Now in your podcast app of choice).

It’s a well known maxim in the tech industry that if you’re not paying for the product, then you are the product. We get to use incredible services like Gmail, Facebook and Twitter1 for free – and in return, the big tech firms sell access to our eyeballs to advertisers2.

But this isn’t always the case. Sometimes, even when we pay for a service, we’re also the product being sold.

For example, something that EE, O2 and Vodafone all do, but don’t really love to shout about is sell anonymised, aggregated data on our physical movements to local authorities, transit agencies and any other companies with a chequebook large enough.

And that’s why today I’m going to tell you about some of the really mad things that Transport for London (TfL) can figure out about us by using our location data, provided by the O2 mobile network.

Using the Freedom of Information Act, I’ve managed to obtain the Data Protection Impact Assessment, and the Statement of Work for TfL’s Project EDMOND – which stands for “Estimating Demand from Mobile Network Data”3.

That’s right, this week’s newsletter is dangerously close to being actual reporting instead of just my usual bloviating. And having now fallen down the rabbit-hole digging into it, I’m amazed by the quality of information it gives transport planners and policy makers. And honestly, I’m a little freaked out.

So let’s dive in and explore it together.

If you enjoy blazing hot takes on politics, policy, and – with alarmingly regularity – transport, then please consider subscribing for FREE to get more of This Sort Of Thing in your inbox. And if you really value my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to get Even More Good Stuff on a regular basis. (More paid subscriptions means that I can spend more time on the free stuff, too!)

Careful now

The way EDMOND works is very clever. TfL isn’t actually monitoring all of our phones all of the time, presumably because it knows that to do so would be hugely controversial.

So instead, it contracts with O24 to license data over shorter periods of time. For example, in 2023, it took data from ‘up to’ 40 normal weekdays between the start of April and end of June, when nothing weird was happening like school holidays or bank holidays5.

This is an enormous dataset, with potentially up to 25 million phones included in it6, but it still doesn’t include everyone in London because some people use other networks like EE, Vodafone, and so on.

So it’s crucial to understand that EDMOND isn’t just a pile of data – it is a model, where TfL has taken the data from O2, and has done some clever maths to scale it up to estimate the the movements of everyone in London over the age of 12.

There is also the elephant in the room. Though it might be surprising to learn that O2 is selling data insights on its users, it is not selling personal data7. What’s being sold by O2 and licensed by TfL is aggregated, anonymised data.

This means TfL can’t see the movements of individual people, and of course everything is fully GDPR-compliant and above board – as you’d expect for a major corporation and a transport agency.

In fact, according to the 2018 Travel in London report, any time the data suggests there were fewer than ten phones in a given statistical area, the data was automatically excluded so to avoid inadvertently unmasking people based on their metadata.

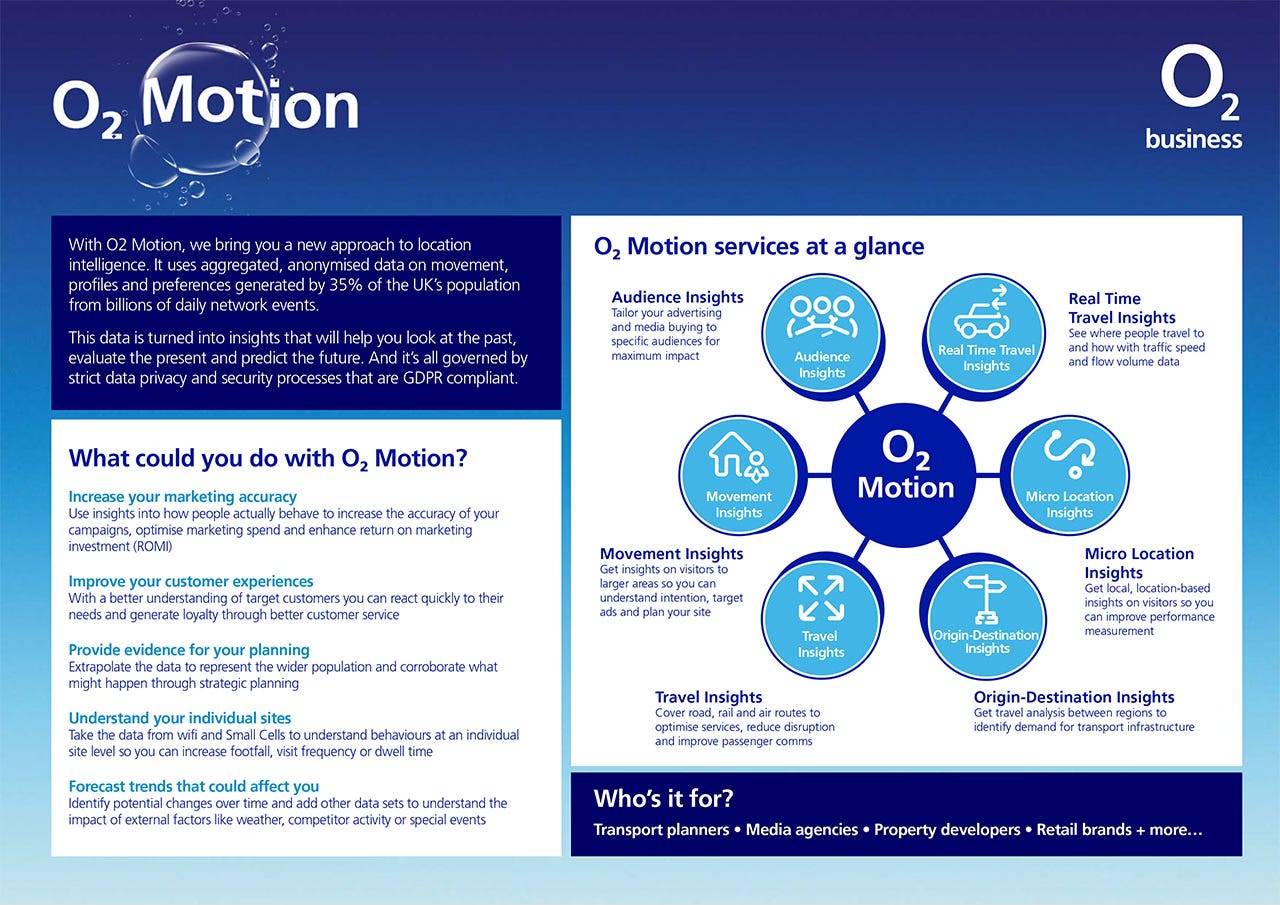

So to be absolutely clear, there’s no big scandal here8. In fact, using this sort of data is increasingly routine for local authorities and others9. To the extent that O2 even has a brand name for this line of its business – “O2 Motion”.

But that doesn’t mean what’s happening isn’t interesting. In fact, I’m willing to bet that most people outside of the mobile industry are completely unaware their movement data is being used in this way.

What TfL knows

Now let’s get to the good stuff. What does all of this data do for TfL, and what data do they have to play with?

Because of the aforementioned privacy restrictions, they don’t simply get dots on the map show them where everyone was. Instead, the data is broken down into hundreds of “Medium Super Output Areas (MSOAs)” – this is a statistical standard that divides up the country into groups of between 2000 and 6000 homes.

Here’s a map showing London’s MSOAs:

Looking at this, you can see why data on this level might be useful.

Using the aggregated data from O2, TfL can see which areas of London people are travelling from and where they are travelling to – which is exactly the sort of information you might need if you were, for example, planning where to run buses or impose an Ultra-Low Emissions Zone that disincentivises car use.

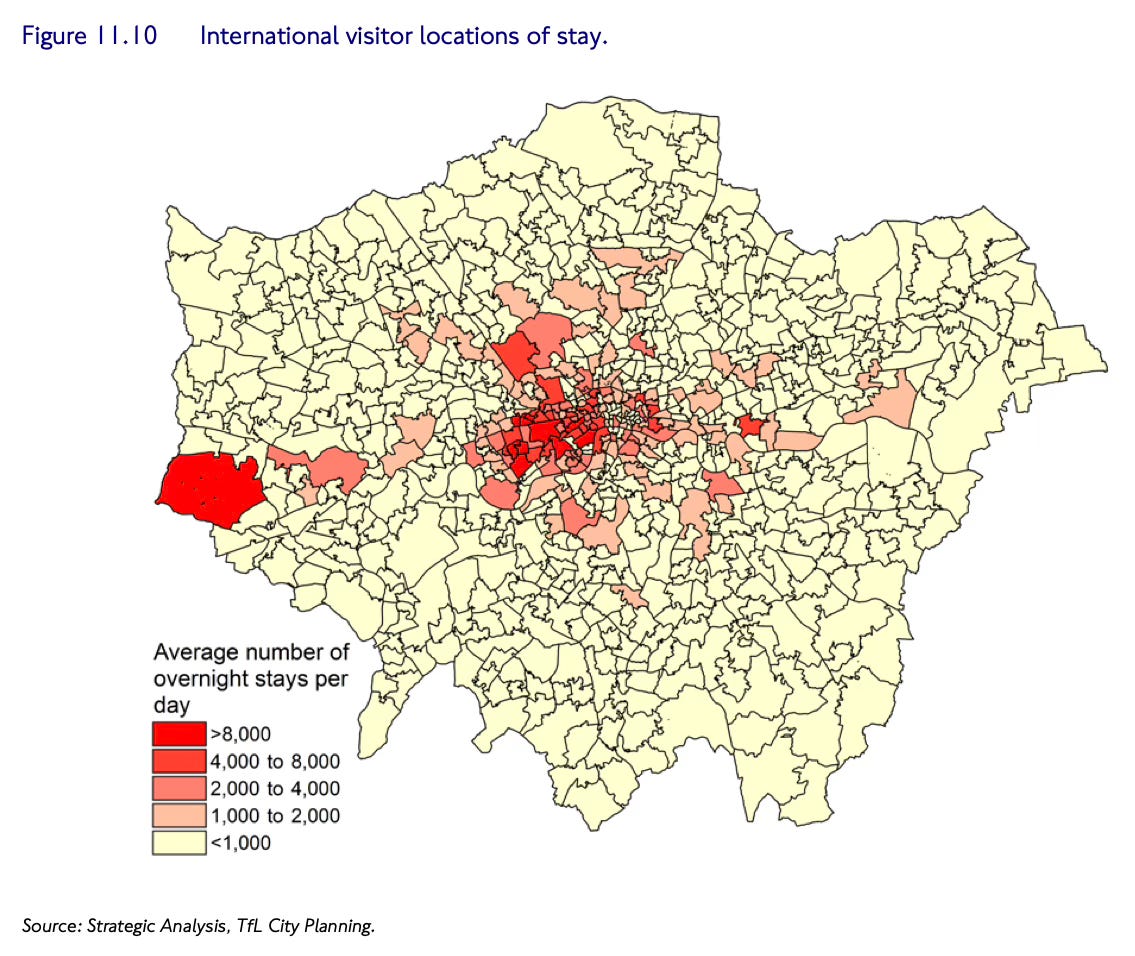

It goes deeper. As you can see above, it’s possible to work out which parts of London are hosting the most international visitors, by looking at which MSOAs have the most phones using international roaming mode inside their boundaries. (Unsurprisingly it appears the busiest areas for international visitors are the West End, and Heathrow.)

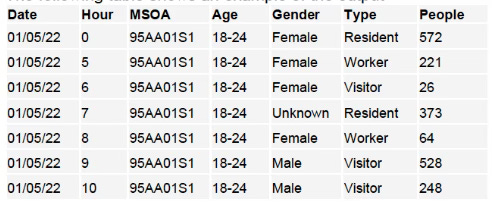

But here’s the other crazy thing. Whether your SIM card is roaming is not the only thing that O2 knows about its users. In fact, because it has demographic data on its contract customers, it’s possible to break down the demographics of people in each MSOA by gender and age – as well as the time of the day they were there.

Here’s some made-up example data showing just that, from one of the documents I got:

Arguably the creepiest column above is the one you can see labelled “type” – which you can see labels different types of people “Resident”, “Worker” and “Visitor”. Because O2 doesn’t just know where you are, it knows why you’re there too.

How does it do this? By making some smart assumptions.

For example, it determines your home by looking at the place where you spend most evenings and nights during the prior month. It also figures out where you work based on where you spend working hours during weekdays. And according to the documents I’ve obtained, it appears that the latest 2023 modelling will also be figuring out when people are specifically travelling to education institutions (ie: schools and universities) too.

So TfL isn’t just able to figure out where people are travelling to and from, but why they are travelling. But amazingly, the model gets even smarter than this.

Mashing up datasets

To my mind, the most impressive thing about the EDMOND model is that it can apparently accurately predict by what means you’re travelling – whether by foot, bike, car, train, bus or even lorry.

This is a really hard question from a technical perspective. The obvious way to do this would be for O2 to look at the speed your dot on the map is moving and the route on which it is travelling. That way, it could conceivably match you up to known bus routes or railway lines. In fact, this is how railway travellers are identified – they look at where clusters of users appear to be moving together, as indicative of groups of people inside a train carriage.

But on London’s busy streets, traffic will sometimes crawl to walking pace. And besides, how can they figure out if you’re in a car, taxi or bus? Or even on a bike? How can it tell the difference?

I’ve seen other devices attempt to figure this out before. My Apple Watch will ask me if I’m cycling when it detects that I’m moving at cycle-like speeds and my heart rate is elevated. And Google Maps will sometimes ask me to rate my bus journey, if it detects that I’ve just checked for when the next bus is coming, and have then travelled along the route of that bus.

But both of these things require access to either the contents of my phone or a monitor for my heart rate. Neither of which O2 has access to.

So instead, the EDMOND model goes into its mind palace and reasons an answer using pure logic, by leaning on TfL’s Public Transport Accessibility Level (PTAL) data.

PTAL is a map of London, divided into thousands of individual squares, each of which has been given a score for how accessible public transport is. Scores range from zero (the bits of countryside that are still technically in Greater London) to 6B – imagine you’re standing just outside Kings Cross station with a half a dozen tube lines, national rail and countless buses to choose from. You can see the PTAL score for where you live on this interactive tool here.

So how does TfL work out how you’re travelling? Because it knows where you’re travelling and the route you’re taking, EDMOND looks at the PTAL scores for the different locations you hit, and basically makes a prediction on the means by which you’re travelling, based on what transport options were available to you.

And here the crazy thing: TfL knows this actually works, as it has validated these predictions against data collected by its more traditional London Travel Demand Survey, which is posted out to households and filled in by people with clipboards. And the data all lines up.

The utility trade-off

So as you can tell, I think this is pretty amazing. From some aggregated dots on the map, the time of day and some demographic data, TfL has built up a really detailed picture of how people are moving around London.

And EDMOND data is, unsurprisingly, widely used internally. It is one of the key tools being used to forecast cross-river traffic for the controversial Silvertown Tunnel, which is currently under construction in East London. And it has also been instrumental in forecasting traffic patterns when rolling out the even more controversial ULEZ scheme.

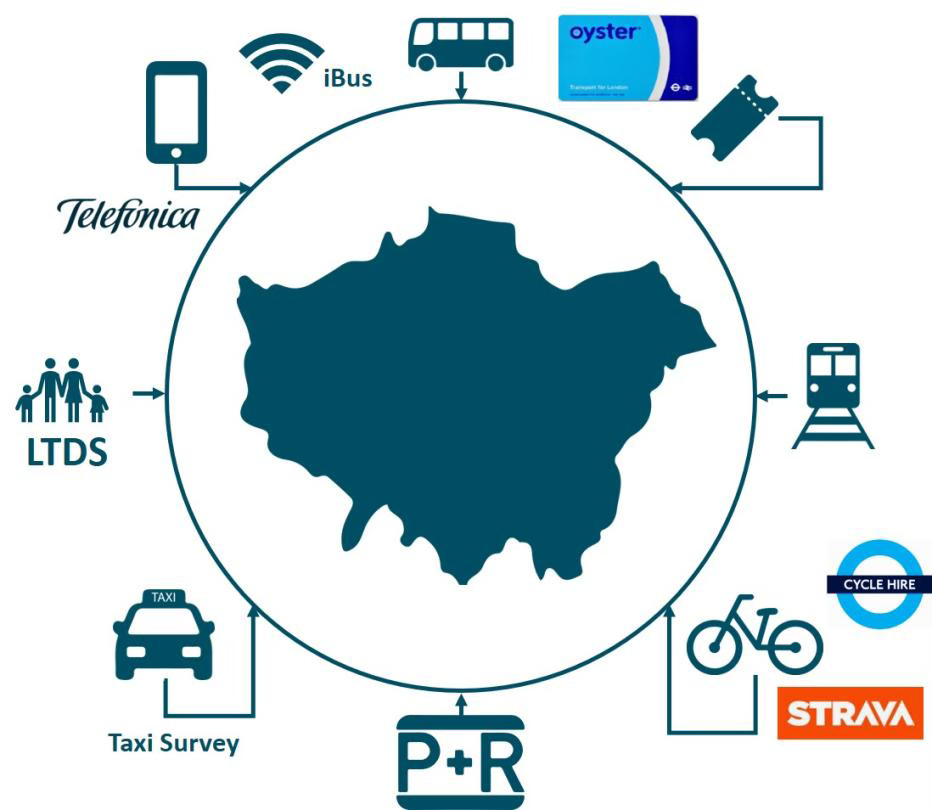

More generally, it also feeds data into TfL’s other, even bigger strategic models, like MoTiON, which incorporates mobile data, Oyster card taps, real-time bus, Boris Bike hires and even data from the cycling app Strava to model how London travels. Which I guess is what it takes if you want to keep a city of nine million people moving10.

However, despite the obvious utility of EDMOND, I’m not sure how I feel about it.

Why? Because the privacy implications weird me out a bit… And I know I’m not the only one.

I’m not really a scoop-getting journalist. I’m more of a “I spoke to some experts and they agree it is complicated” guy. But back in 2017, I broke the story of what TfL had learned from tracking phones on the tube network using wifi11.

The story is similar to this one: That by using wifi pings from our phones, TfL can plot how we’re moving around the Tube network, even if we haven’t connected to the Tube Wifi network. (I recommend clicking the link for some awesome diagrams).

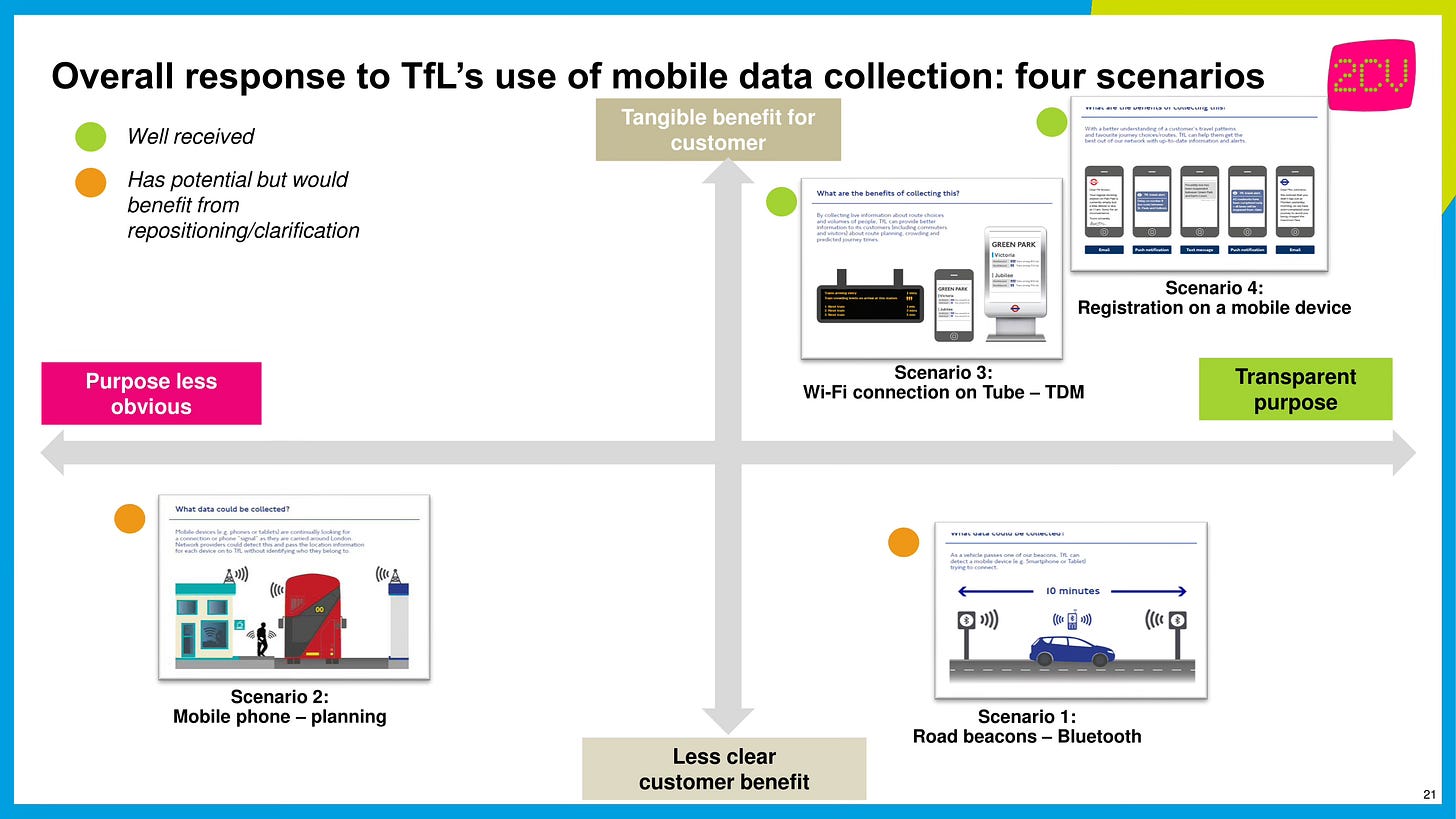

One document I obtained for that story also contained the results of a focus-group study conducted for TfL, basically testing the attitudes of the public to different types of mobile data tracking. The results of which you can see on this matrix:

As you can see above, wifi tracking was received quite well. People understood the purpose for doing so (it helps TfL manage the Tube network, and can work out how crowded trains are – data which can today be seen by passengers in transport apps). And the data collection was perceived as relatively transparent, presumably because tracking can be sign-posted inside stations, and that it’s possible to opt-out by switching the wifi on your phone off.

By contrast, taking data direct from the mobile networks, as seen in the bottom left of the diagram, was more poorly received – with people unsure why it was being done, or how they would benefit.

I think this reaction from the public is pretty understandable. It is literally the case that the major phone networks are recording our movements and building up a surprisingly detailed picture of the places we sleep, work and hang out.

But to be fair TfL does appear to have approached using the data in the most minimising and proportionate way possible – by taking a small sample of anonymised data, and using it to build a model, instead of setting up a system that collects data around-the-clock, in real time12. So I can’t really fault TfL for using the data. The fact that O2 is willing to sell these anonymised data insights must be irresistible if you’re managing a transport system, especially in a city as complicated as London.

So what I am perhaps more sceptical of is the fact that this data is being collected and sold by the phone networks in the first place.

Because think for a moment about what they need to collect to make it work. It means that somewhere inside my phone network’s databases are my movements for at least the last month – revealing everywhere I’ve been, who was in the same place as me at the same time, and just how many times I’ve shamefully stopped in at Burger King on the way home, because I can’t be bothered to cook anything at home.

Though TfL and the networks’ customers only get the data in an anonymised, aggregated form, that’s not true of the networks, who need to store and analyse my actual data to make it useful13.

Perhaps, arguably, this is a good thing. You can imagine how, for example, it could make it easier for the authorities to hunt down a terrorist on the run. Slightly further down the slippery slope, you can imagine how this same tech could also be used by the security services to find everyone who attended the Hizb ut-Tahrir protest over the weekend, and within seconds tell them not just where attendees live, but where they are right now14.

Whether that would be proportionate or not, I’m not sure. But what’s obviously true is that at a certain point, the civil liberties arguments become important.

One useful gut-check of any new technology is to imagine how it might be used by a bad actor. You don’t have to think too hard to imagine how such tracking technology could be misused by an authoritarian if they were to somehow come to power15. There is definitely potential for what Edward Snowden calls “turnkey tyranny”.

The question for policy makers and voters then, is how do we trade off between the utility of data analytics like the networks are selling, and the potential risks that we’re building tools that could conceivably, if things go badly wrong, be used as the tools of oppression?

And as an unsatisfying ending to this piece, I’m not sure in the specific case of EDMOND where the balance lies.

I think it is definitely a strong case for why we should do our best to build strong institutions to protect our democracy, so that we can more safely take advantage of new technology, and build a more functional society, without any of our rights feeling threatened.

But even if we decide that the networks closely tracking us is fine because it is useful, we should be careful to maintain a healthy scepticism too. And that starts from actually knowing it is a thing that happens. So at least now you’ve reached the end of this article, you and hopefully a few more other people will know about it. Now if only EDMOND could also figure out what we should do with this information too.

Phew! That was a long one this week. But if you enjoyed reading it then make sure you subscribe – for FREE (or if you’re nice, paid), to get more articles direct to your inbox. These articles take several days each to produce, so they only happen with your support.

As you’re interested in transport, you might like this one about the surprising good things in Rishi’s Plan for Drivers. Or maybe this one about extending the Elizabeth Line into Kent. Or maybe even this one arguing that ‘misinformation’ isn’t the problem with the EV transition.

Perhaps not quite as “incredible” recently.

Contrary to the popular cliche, the big platforms, like Google and Meta don’t actually “sell our data” – they match advertising content with us while keeping our data to themselves. So if someone buys an advert on Google or Facebook, the advertisers don’t like, get your email or IP address – they just get the platforms’ assurance that their ad has reached someone who matches their targeting criteria. The real risk from data being sold is from smaller companies, which might be less scrupulous, or have a different business model…

Though other TfL documents suggest it stands for “Estimating Demand Matrices from Network Data”, so who knows?

Technically Telefonica, O2’s parent company, but that doesn’t matter, so I’ll stick with saying O2 for ease.

As far as I can determine from the documents, TfL has only re-sampled the location data three times: First, an initial trial in 2016. Then again in 2019 as it was getting out of date. And then, well, you know, the world changed. So now it is currently rebuilding the model with 2023 data to see how we’re moving around post-pandemic.

Though according to this guy, this was filtered down to a ‘core sample’ of 15 million phones, to remove devices that aren’t used very often. Still, that’s a lot of phones!

It’s a little similar to how the Postcode Address File isn’t technically personal data. Well, not really that similar, but I feel it is important to mention the PAF again.

I realise I should probably pretend it’s a massive scandal so you keep reading, but I’m confident my readers are sophisticated enough to appreciate a good graph or map when they see one, and that’ll be enough to keep you scrolling.

For example, say you want to open a shop, you can pay O2 to use mobile data to identify the size of your total addressable market, based on how many people are in travelling distance from where you want to open.

If any TfL insiders want to geek out with me and explain how this all works by all means email me as this sounds incredible.

Web Archive link because of the infuriating decision to remove Gizmodo UK from the internet when it was shuttered.

O2 boasts that if a customer wants it, it can provide data in “near real-time”.

Though I’m sure they encrypt it and do all of the best practice stuff to keep the data secure, blah blah blah.

Whether this is legally possible I’m not so sure. But my point is that the infrastructure has been already built to make it possible on a technical level.

I’d be absolutely amazed if the Chinese government doesn’t already routinely collect and store movement data, and if there isn’t some system in Beijing where they can type in the names of any citizens and get a breakdown of their movements.

The Telecom Security Act 2021 is relevant here, as one of the intentions of that is to prevent malicious actors from gaining access to the personal data held by mobile networks.

And I think the PTAL data needs updating as the "forecast 2021/2031" maps don't seem to show the impact of the Elizabeth Line, Nothern Line to Battersea or even the more recently upgraded parts of London Overground

Correct me if I’m wrong, but if it’s aggregated and anonymised, it shouldn’t be possible to reverse engineer it to get the personal data right? (Esp given the “we don’t collect if there’s only 10 people” safeguard you mentioned”). Cus if that’s the case I don’t think I have a problem at all with it. Aggregated data collection is v important, and I don’t think a huge complex society can function without it. There are so many things we could improve if we were able to have the anonymised aggregated data available to be studied (e.g: healthcare, treatments etc). Ofc we need the proper safeguards in place to prevent data being badly used, but if we accept a census as a normal thing, because of the way that provides us crucial data (that is anonymised and aggregated) then I think it’s fair to do so with other forms of anonymised and aggregated data, and we don’t have to worry about that. I think people not knowing is slightly problematic, but I’m not against anonymised aggregated data on principle