Why has the government published a NIMBY charter?

In which I expose a potential CIA plot

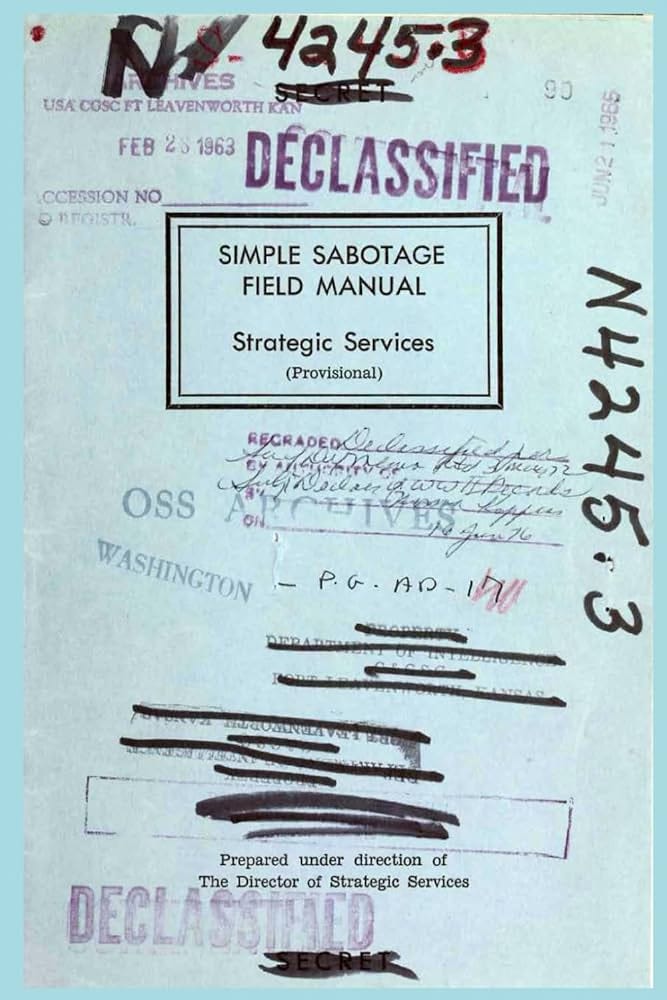

In 1944, the United States Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to the CIA, published a guide for spies and saboteurs embedded behind enemy lines, in German-occupied Europe.

The ‘Simple Sabotage Field Manual’ wasn’t a recipe book for making bombs nor advice on how to shoot a gun. Instead, it proposed techniques and strategies to slow down the Nazi war machine through arguably a more dastardly weapon: grinding bureaucracy.

The idea was that by intervening in meetings in just the right way, agents could jam up the ability of the Nazis to get anything done.

For example, some suggestions for sabotage include:

“Insist on doing everything through ‘channels’. Never permit short-cuts to be taken in order to expedite decisions.”

“When possible, refer all matters to committees, for ‘further study and consideration.’ Attempt to make the committees as large as possible- never less than five.”

“Haggle over precise words of communications, minutes and resolutions.”

“Refer back to matters decided upon at the last meeting and attempt to re-open the question of the advisability of that decision.”

“Advocate ‘caution.’ Be ‘reasonable’ and urge your fellow-conferees to be ‘reasonable’ and avoid haste which might result in embarrassment or difficulties later on.”

As you can probably tell, it’s sort-of ingenious, and these techniques will be instantly familiar to anyone who has ever had a painful work meeting.

There is, however, a more specific reason that I mention it.

A couple of weeks ago, a new research and analysis paper was published by the Government Office for Science, the bit of the civil service that works directly for the Government’s Chief Scientific Adviser.

Titled “Principles for navigating the social aspects of grid transformation”, the document “sets out 8 broad principles for navigating the social aspects of the accelerated transformation of electricity grid infrastructure in the journey towards net zero, energy security and lower energy bills.”

And frankly, it is a pretty horrifying read for anyone who thinks we should… actually build some pylons and other electricity infrastructure – to the extent that I’m wondering if Britain has been secretly infiltrated by the CIA.

Like takes on politics, policy, infrastructure and other nerd stuff? Then you’ll like my newsletter. Subscribe (for free!) to get more like this in your inbox.

Just say no

Let’s look at some of the recommendations in the document. Imagine we need to build some new pylons – which we very desperately do. How does the paper suggest we go about doing it?

First, it recommends engagement with the public.

“Engagement must begin as early as possible, ideally before critical decisions are made, and continue throughout a project or development.”

On the surface, this may not sound so bad. The authors particularly emphasise consulting people before any construction or planning begins – and then keeping people involved throughout the process.

And hey, who doesn’t think that it’s good to always consult people like this?

The answer is me. Because this is one of the specific pathologies that has slowed Britain’s ability to build to a crawl. In fact, an overly-bureaucratised need to consult is one of the core problems that the Planning and Infrastructure Bill is attempting to address.

So though consultation isn’t always bad, we need to do it carefully. If we stop to consult too much, nothing actually happens – and given that it currently takes between 12 and 14 years (!!!) on average to build new transmission infrastructure, it already takes far too long without extra layers added on top.

Then there is the next section, which hits upon another paralysing pathology: a total and utter fear of upsetting anyone.

In a section titled “Place-specific knowledge and emotions should be valued”, we’re warned that:

“Regardless of levels of technical knowledge, people possess important local experience or tacit knowledge about the places they live, their histories, and realities of daily lives. People also hold a range of often overlooked emotions (such as pride, fear, interest, and many others) about the grid or energy infrastructure and the institutions involved, and these emotions play an important part in the success of transitions or changes.”

At the risk of being unkind, I’m not really sure emotions are that important to the success of the energy transition, at least relative to, say, actually building some pylons.1

This tendency for conflict aversion is reflected elsewhere in the document too, such as when it cautions against the use of the other N-word:

“Care needs to be taken around the language used to talk about people and communities. Phrases such as obstructionist, blockers, NIMBY’s (Not In My Back Yard), can risk derailing engagement before it has begun. Often, not everyone will be happy about the changes, and there may be groups of people who seek to block the proposed changes. However, many communities have valid and reasonable concerns about infrastructure change based on attachment to place (among other factors).”

This was the moment when I felt like I was going insane. Because as much as we might like to pretend that we can reason people into seeing sense, such as by using the right language or understanding their emotions about pylons better, the reality is that new construction near existing homes is never going to be hugely popular with existing residents. No amount of clever argument or ‘engagement’ is going to talk people out of reacting to their material circumstances.

That’s why I think we have to accept that sometimes in politics, you have to do unpopular things or make ‘difficult choices’, as politicians like to say, for the sake of the greater good.

To think otherwise is the same fallacy we see when activists advocate Citizen’s Assemblies as magic cheat codes to get around difficult issues. You can’t take the politics out of politics.

And I think this is something that the document is terrified of admitting. Sometimes you have to upset people, because the alternative is much worse: if we don’t build pylons, we can’t move energy to where it needs to be. That means bills will be higher and economic growth will be more sluggish.2

The scourge of Everythingism

So this is all to say that I think where the analysis fails is that it doesn’t recognise the real trade-offs involved. Instead, it acts as a one-way ratchet, proposing extra burdens to the development process, without recognising how all of these superficially ‘good’ things can add up to something bad.

It’s the same problem we see with planning more generally, where over the years extra rules have been imposed, each for inoffensive reasons – who wouldn’t want environmental assessments, or to assess the heritage impact? But cumulatively, they make building harder.

And I think the ultimate example of how this reality simply isn’t taken seriously by the authors comes later in the document, in a section about “Fairness and Justice”:

“The changes in the grid will have very diverse impacts on different groups and the benefits of the changes will also be distributed unequally. The evidence suggests that without action, these impacts and benefits may reinforce pre-existing inequalities. The scale of grid transformation needed has not been seen since the 1950s and so the proposed changes are also a unique opportunity to address certain inequalities.”

In other words, the authors are arguing that any building projects should go beyond a tractable problem like “we need to build some pylons”, and are doing their best to turn it into an intractable one, like “we need to build some pylons and dismantle capitalism”.

It’s a problem that Joe Hill from the Re:State think tank memorably named ‘Everythingism’:3

Everythingism is the belief that every proposal, project or policy is a means for promoting every national objective, all at the same time. Trade policy is not for getting cheaper goods, but for reshaping the global economy. Planning policy is not for getting high-quality housing near the best jobs, but creating local jobs, hiring more apprentices, and enhancing biodiversity. And Government procurement isn’t for the best products and services at the cheapest price. It’s about promoting “social and economic value”, reshaping the British economy to promote Net Zero, regional economic development, and diversity and equality training.

Because of Everythingism, we never do any one thing well, we do everything badly. Housing policy becomes the main route for fixing the nitrogen imbalances in local rivers, and creating more social housing the main way of subsidising the welfare state. Trains must look after bats. Climate policy is to support the services sector.

This is ultimately why I think this document is basically a NIMBY Charter. It’s not proposing a better process for building out energy infrastructure – it’s concern trolling and turning the ratchet further in one direction, to make it easier to oppose or slow down building.

And what’s annoying is that we know why this is bad. In fact, we already have a startling example of it in the form of HS2.

In that case, the project has gone wildly over budget and is taking much longer than planned because instead of just building a railway line to a set plan, over the last two decades the brief has been repeatedly rewritten – with so many layers of consultation and engagement that seemingly every small village on the route has been promised its own tunnel, to hide the new railway away.

And instead of simply laying down some track and putting a train on it, the project has encompassed every conceivable problem along the route – hence the infamous £100m bat tunnel.

Trust the experts?

There is some good news about this paper. Even though it has been published on GOV.UK by the Government Office for Science, it is very explicitly flagged as not being a statement of government policy. It is only, we are told, a piece of research and analysis.

However, even so I worry about how it will be used in practice. To be honest, I’m not entirely sure what it will be used for. Maybe it will be buried in the bottom of a metaphorical filing cabinet and forgotten about?

But equally, perhaps it will be handed to civil servants working on transforming the grid as informal guidance or advice? And if they take the recommendations seriously, it just means the slowing down of deployment, delays to construction and extra zeros on the end of the bill.

I also worry that regardless of the specifics of this document, that it represents a much broader cultural problem in the civil service – and the pathologies that have trapped Britain in its economic and political malaise.

And what’s most frustrating is that as well-intentioned as these principles may be, the authors are clearly missing the big picture. I mean, I’m sure that everyone who worked on the paper believes that climate change is very important. But if we want to have the infrastructure that Net Zero requires, we need to build, not consult and compromise!

Then more speculatively, I’d also guess that the authors are just as worried about Nigel Farage winning the next election as I am.4 Yet instead of recognising the urgent need to deliver as fast as possible, and to demonstrate results on the ground, this NIMBY Charter just sets out new ways to obfuscate, delay and dampen the infrastructure that we’ll need if we want the economy to grow.

So I hope that anyone in government who is handed this document will treat it with scepticism as it is little more than a guide to making sure nothing happens. And who knows? Perhaps it could even be a CIA plot.

I can’t claim to have read the paper the emotion claims are based on in detail, but let’s just say… Hmmm.

Though this leaves aside the fact that the people who live near new infrastructure will also share in the upside of lower bills, economic growth and the lights in their homes staying on.

Don’t be confused, the think tank used to be named ‘Reform’, but it’s not that Reform.

They’re scientists working in the public sector – a demographic where I’d guess Reform support is currently around ~0%.

Great piece.

As you say, most people aren't going to want pylons. Either you accept that a legitimate authority can make unpopular decisions in the national interest, or you establish a framework where companies can (swiftly and transparently) buy off opposition - e.g. local vote by residents on accepting a certain cash payment offered by the company - and if accepted, no further challenges.

On your last point, I'm afraid I do think this culture and these attitudes are endemic in the civil service.

And even aside from the problem of something not getting built at all, it's also surely a very bad idea to create incentives in which increasing the volume of NIMBY activism succeeds in moving a scheme from one place to another. You're right that some people will be upset by a Decision From On High that affects their life, but if the reasons are laid out transparently and clearly, I think that would do much more good psychologically vs the implied hint that "if you organise the locals well enough against this, you might succeed in getting us to move the thing" to Place B (whose locals then know that the only solution is to shout even louder)