The social justice case for self-driving cars

Abundant mobility should be a moral crusade

If you think that self-driving cars aren’t happening, then I’m afraid you’re living in denial – because they’re already here.

Today, in a handful of cities around the world, it is possible to summon an autonomous taxi with the same ease as hailing a human-driven taxi service like Uber, Bolt or Lyft.1

For example, in San Francisco, Google operates an autonomous taxi service called Waymo. Cars really do drive themselves, and they do not arrive with a back-up human sat behind the wheel, ready to take over if something goes wrong. Instead, the driver’s seat remains empty and en route it’s just the on-board computer and a bunch of sensors getting you to your destination.2

What makes it more remarkable is it is not an experimental pilot programme for a handful of specially selected individuals. Instead, Waymo is an actual commercial service. Any customer who wants a lift from an autonomous robot can get one, just by downloading an app.

And Waymo is not the only one. There are similar services in other places, such as one operated by Chinese tech giant Baidu in Wuhan, Beijing, and Shanghai and a few other places.

Outside of taxis, we’re also seeing autonomy rapidly improve elsewhere. As I’ve written previously, Tesla’s “full self-driving” technology is getting surprisingly good. And, unlike what many critics claim, this emerging autonomy isn’t just a technology for sunny Californian weather – as evidenced by a company called Wayve here in Britain. It has been testing fully autonomous driving in central London, and for technical reasons I won’t go into, it’s arguably an even more sophisticated form of self-driving than the one used by the likes of Google.3

In other words then, at long last, after decades of false dawns, autonomy really is happening.

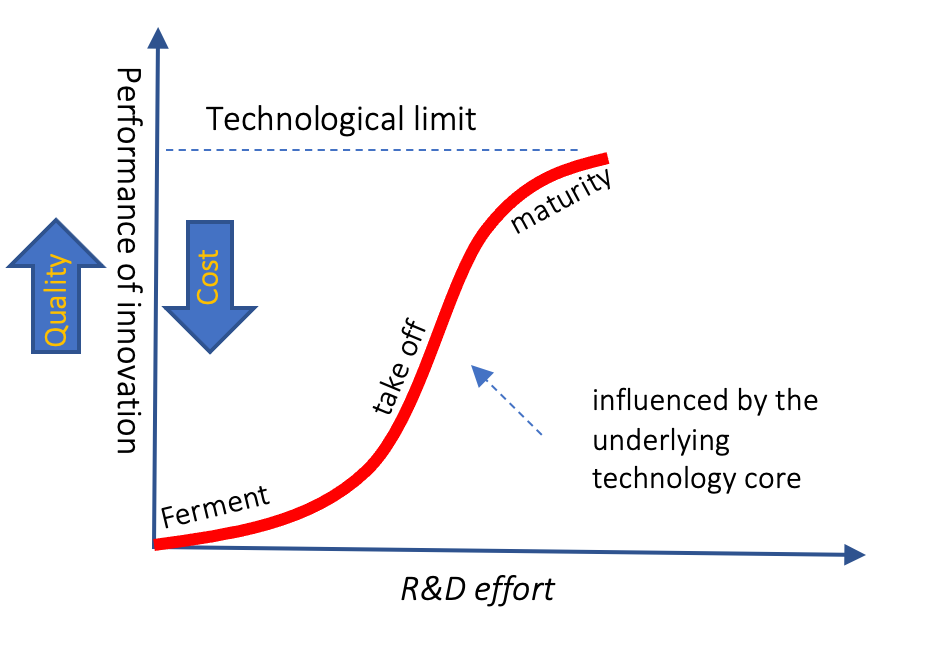

We’re currently climbing the first, slow incline of the innovation adoption “S-curve” - the process that every new technology tends to go through. A bit like how when the iPhone first launched in 2007, and when it cost £1000, relatively few people had one - but by around 2012 when the technology improved even further and costs fell, growth exploded and smartphones were quickly ubiquitous.

I’m sure that given strict safety requirements and regulatory complexities, the S-curve will not be quite as smooth for autonomous vehicles as it was for smartphones.4 Nor will autonomous vehicles appear everywhere at once (we’ll probably get autonomous buses and lorries first).

But the reality is that this story only has one ending, and that is in a medium-term future where self-driving cars are a part of every day life for millions of people.

And this is where I think something is missing in the discourse around what this major technological transition will mean for our world.

Making the positive case for autonomy, we have the tech companies themselves. They are, obviously, promising that self-driving cars will make our lives easier, as they will make travel more convenient – and that the roll out of self-driving will make a positive economic impact.

This is all true. But I also think that the pro- arguments tends to be pretty bloodless. Whether society should adopt self-driving cars is typically framed like a procurement decision – without reference to emotion or morality.

And this, I think, is a shame.

It’s why the latter style of argument is something the sceptics of autonomy are much better at. Sure, they will often make opposing practical arguments – arguing (wrongly, in my view) that the technology is not yet there. But more importantly, autonomy sceptics will often point to moral arguments to bolster their side.

For example, they will point to how software will have to make trolley-problem-style decisions, or worry about what the new technology will mean for the power of Big Tech, or the impact on privacy or jobs.

These are all valid concerns. But this is where I also see a gap in the discussion. While we can argue about whether the technology is truly there yet, we don’t see much of the argument for autonomous vehicles framed in moral terms.

And this seems strange to me, as I think there’s not just a powerful economic case in favour of embracing and accelerating the autonomous vehicle transition, but a powerful social justice argument in favour too.

Now to explain why, I need to take you not to Silicon Valley, but to Kuala Lumpur.

Get my politics, policy, media and tech takes direct to your inbox by signing up (FOR FREE!) to my newsletter.

Abundant mobility

Before Christmas, I spent a few days in Kuala Lumpur - or ‘KL’ to the Malaysian locals. As cities go, it has something of a chaotic aura. The centre is a forest of skyscrapers, but down on ground level, the bustle of pedestrians and traffic feels far more intense than any British city.

It’s also not a particularly friendly city for visiting tourists. Not because of the people, but because getting around is challenging.5 There are few buses, only a handful of train lines, and in many places there’s a distinct lack of pavements. And I can attest from a deeply unwise, first-hand experience that it is a city where you very much do not want to try and travel by e-scooter.6

However, there is one clever travel hack that can instantly make the city much easier to navigate: Being rich.

In fact, if you live in Britain and earn a reasonable income by our standards, then in Malaysia you are, functionally, pretty wealthy. And with your British income, travelling around KL becomes instantly easier, thanks to an app called Grab.

Grab is a ‘mobility’ app and is essentially the South-East Asian equivalent of Uber – it’s nearly identical, down to the design of the user interface. With a few taps on your phone, you can summon a human-driven taxi to take you to wherever you need to be, or have a human driver on the app bring you food from a local restaurant.

Unlike in Britain though, where for most people taxi rides and takeaways are a somewhat pricey occasional treat, because wages in KL are dramatically lower the marginal cost of using Grab is trivial.

For example, the cost of a door-to-door 5km Grab trip while we were there cost just 8.24 ringgit – £1.42 – or slightly less than a bus ticket in London. But on this journey, we had three of us sharing the car, so it was even cheaper on a per person basis.

In other words, the cost of travel was so low that we didn’t even stop to think about it at any point. And the consequence of this economic reality was that it completely transformed how we approached and understood the city.

It meant that for the four days we were there, we essentially experienced KL with personal chauffeurs taking us everywhere we wanted to see, door-to-door.7 And on the evening when we were too tired to go out for dinner,8 we got food delivered to us and the fee for the delivery was basically nothing.

Perhaps you can see where I’m going with this.

I don’t explain all of the above to boast about the fun holiday I just had, nor to invite an uncomfortable conversation about the optics of British people in a former colony being driven around and waited on by much poorer locals.

But I describe it because if we try to imagine what our lives might look like when autonomous vehicles are ubiquitous then the world probably looks… something like what I experienced in KL.

If taxis and deliveries of the future no longer require drivers, then the marginal cost of ‘mobility’ will collapse. It will mean that what I’ll call ‘abundant mobility’ will not only be available to rich people visiting a much poorer country where labour is cheap – but it will be for available for everyone, everywhere. And this will be a very good thing.

Living like a King

Imagine a world where the cost of movement is no longer expensive enough to think about.

Suddenly geography becomes less of a barrier in our lives, as getting between places is more a question of time than cost. If we need something - whether food, medicine or anything else, it will be economical to have it brought to our front doors, or for us to go directly to it, from wherever we are.

This isn’t just about lazy takeaways though. The reason we should work to achieve abundant mobility is because it could have profoundly uplifting social justice consequences.

Reducing the cost of movement means an improved standard of living for people. It means a world that is more accessible to everyone. And it means more opportunities for everyone to take advantage of.

Take housing for example. If the cost of transport is trivial and autonomous transport is permanently available, it unlocks new places for people to live, where previously they might have needed a car, or where traditional human-driven transit does not make economic sense.

This isn’t the only advantage. Abundant mobility could also bridge the urban/rural divide, knit communities closer together, and facilitate human connection more broadly. Autonomous vehicles could help the elderly remain close to their families, and help them fully participate in society for longer. And for younger people, it means more connections to work, leisure and new opportunities. And it goes without saying that reducing the cost of movement will disproportionately benefit those on the lowest incomes.

There are less sympathetic improvements to our lives that autonomy could make too. Abundant mobility will mean we can more easily get our hands on more stuff. Sure, it doesn’t feel as high-minded as, say, autonomous vehicles helping the elderly get to the hospital, but it still matters as the material circumstances in which we live affects our wellbeing, and how we feel about our lives.9

For example, getting a fancy coffee brought to your door in the morning might not be the most capital-S-capital-J social justice consequence of abundant mobility, but it’ll mean a world where the average person can live like the rich do today.10 With autonomy, the fruits of modernity will be more evenly shared – just as prior technological revolutions mean that today almost everyone on Earth has access to comforts that Kings and Queens in past centuries could never even have dreamed of.11

Free the movement, free the people

Realistically, it’s unlikely the cost of mobility will fall to zero. This is for a number of reasons: Firstly, the companies currently working on autonomy will want to pay off their capital investment used to develop the technology in the first place. And even if the cost of a human driver is removed, there will still be other marginal costs, such as the cost of electricity and vehicle maintenance.

And then of course there is the fact that space on the road still has an element of zero-sum competition. Though autonomy can make our roads more efficient, it will remain true that every individual travelling in their own autonomous taxi is unworkable in, say, central London.

So traditional transit, like trains, trams and buses will still have an important role in the future transport mix. New technologies like drones and autonomous, ground-crawling delivery robots (pictured above) will be vital too. To ensure there is space for these high density modes, the allocation of road space will have to be rationalised – adding to the cost of taking an autonomous taxi (like by using road pricing) seems like an obvious way to regulate this – which suggests future travel will have some costs.

And in reality, there will also probably be significant political challenges in making the autonomous transition work too.

For example, there are 100,000 Uber drivers in the UK alone. Those are all jobs that could – and probably will – disappear when self-driving tech rolls out. And as mentioned above, there will still be perennial concerns about the power of individual tech figures.

But the transition being difficult doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t do it. In the longer run, the challenge isn’t to reduce costs to zero. What matters more is the direction. Much like how low energy bills are preferred to high energy bills – the goal here is to reduce the cost of movement overall. And enthusiastically embracing abundant mobility is the best tool we have to achieve this.

So that’s why I really do, completely unironically, view the transition to autonomous vehicles as a moral mission. Rich people today can already live a life of abundant mobility – but soon we will have the technology to make sure that everyone can live as they do.

Phew! You made it to the end. If you enjoy mildly contrarian politics, policy, media and tech takes you will enjoy my newsletter. Subscribe for free now to get the next essay direct to your inbox:

The “ride sharing” apps hate being referred to as “taxis”, because it might invite closer regulatory scrutiny, but I’m going to keep doing it out of pettiness.

To be clear, Waymo autonomous cars do have some ability receive remote instruction from humans. If they get into a spot they can’t handle, a human in a control room somewhere will step in. Though as far as I can tell in the case of Waymo, the remote controller is not ‘driving’, in the sense that they are turning a virtual steering wheel or pressing a virtual accelerator. Instead, they aid navigation and set way points, and the car itself figures out how to drive between them. Whether or not this violates “true” Level 5 autonomy – it’s definitely one approach to handling edge cases, and you’d have to be mad to deny that (eg) one supervisor managing some number of cars on the road isn’t an enormous productivity improvement over having one driver per car.

Essentially the way Waymo works is partially AI training, but also by following hard-coded ‘rules’ that have been dictated by it’s developers. Wayve, by contrast, is reportedly a fully “end-to-end” AI approach, where the developers haven’t told the system the rules of the road or provided a detailed 3D map. Instead, it is driven by an AI model that has learned to drive fully by training. The developers claim that with this approach, they’re able to drop their cars into even unfamiliar places (like taking a car trained in London to Manchester), and have it drive around autonomously without extra work.

Weirdly I think the thing that makes it hardest to envisage at the moment isn’t the technology - which is almost there - but the business model of the transport industry. Right now, we buy and own our cars, but autonomy will surely lead to new ways of structuring this part of the economy. Perhaps no one will own their own car in the future? But either way, this restructuring will inevitably happen if the technology is there - just like how the first version of the web replicated the analogue world (static websites displaying news articles), and it took until “Web 2.0” to for the new paradigms (social media, etc) to emerge.

At least compared to European cities like London, Paris, Berlin, etc.

To get a sense of how chaotic the roads are, when I rented an e-scooter one evening, contrary to every other city I’ve visited, the app insisted that I ride on the pavement.

I strongly recommend a trip to the Batu Caves to see the extremely entertaining monkeys that have learned to steal food and drink from tourists.

Our £36 a night apartment also had access to a 44th floor infinity pool, which was nice.

There’s also a tonne of second and third-order things that autonomous vehicles could make possible that will positively impact lives.

Say that you’re on a video call with your doctor, and they decide that you need to have your blood pressure measured: With no expensive humans in the loop, we could have roaming pods containing medical equipment for people to test at home (guided by a doctor watching remotely).

Or what about bin collections? Instead of being at the mercy of one collection a week, we could have autonomous bin trucks that roam 24/7, and that can be summoned remotely. So that when your bin fills up, you could instantly dispose of it.

And need to get up at 4am to get to that 9am meeting in another city? Why not hire a robotaxi containing a full lie-down bed and sleep your way there?

Here’s a slightly mad prediction: In an abundant mobility world, it won’t be unusual to see flats built without a kitchen. Because if you’re a young, urban professional – why bother to cook, when a restaurant can cook your every meal and deliver it for a negligible fee.

Henry VIII might have had mountains of gold and absolute power, but did he have air conditioning, vaccines and iPads? No he didn’t.

There's also a big opportunity to redesign cities. We won't need as much parking is vehicles are continuously moving around, rather than being parked for ~90% of the time like private vehicles are now.

Plus on a more important note, they might save rural pubs.

Like you I'm pro driverless, though mostly for the very boring reason that even the best drivers have bad days and most of us are not the best drivers. But I'm a bit more sceptical about how ready the technology is. I don't think I've seen anyone operating at what I would call true class 5 yet because they're all geographically bounded - even if those boundaries are expanding. It feels like those limits hide/avoid lots of the thorniest problems that mean the last 20% of development that takes us to 'get in anywhere, any time, any conditions (that a human could drive in) and go anywhere' will take another 20 years for mass availability. Though that probably fits within your definition of 'medium term' and I'll shut up now.