The Twitter/X account geolocation feature should be treated with scepticism

And surely BBC Verify should actually... verify... things?

A strange story was published yesterday by BBC Verify, the department of BBC News dedicated to debunking misinformation and confirming the veracity of claims on social media.

The story was titled “How X’s new location feature exposed big US politics accounts”, and it is about a new feature that has just gone live on Twitter (I will never call it ‘X’), which purportedly reveals the ‘real’ location of accounts on the platform.

It does this by geolocating users using their IP address, and stating from which country’s app store the user downloaded the Twitter app. For example, here’s mine, revealing that I am based in the United Kingdom.

The BBC story goes on to explain how this new feature has revealed that a number of prominent and influential Trump supporters are not actually based in the United States.

Needless to say – as soon as this feature hit, both Twitter and Bluesky were awash with revelations about dozens, ft not hundreds, of accounts. And it was, of course, widely celebrated by Trump (and Musk)’s detractors, as in one fell swoop, a few lines of code had seemingly revealed the scale at which social media is being manipulated by foreign actors.

What makes it all the more amusing is that the feature was implemented by Nikita Bier, Twitter’s Head of Product, after it was pitched by a conservative commentator, who was presumably hoping to prove foreign bots were responsible for much of the anti-Trump posting. So the move was the Trump movement hoisting itself by its own petard.

In other words, it seems almost too good to be true.

And here’s the thing. I think perhaps it could be. Or at least location claims via this new system should be treated with significantly more scepticism than they are being, by both the BBC and the denizens of Twitter and Bluesky.

Reasons for scepticism

It brings me no pleasure to voice this scepticism. I hate Trump just as much as everyone else, and would very much like it if my online nemeses also turned out to be disinformation bots based in other countries.

And to be clear, I think it is likely that many of the geolocation surprises surfaced by this new feature will turn out to be true.

But my point is that we shouldn’t treat Twitter’s geolocation as the gospel truth. The bar for assuming what it says is true should be higher. And we should reserve our enjoyment of these revelations until we can find more concrete evidence.

This is because geolocation is actually quite hard to do, and is often imprecise. Though an IP’s location can be deduced relatively reliably, there are still enough sources of ambiguity to give pause. Perhaps the user could be posting from behind a VPN, tricking Twitter into thinking they are posting from another country. Or they could simply be on holiday.

I mean, I just got back from a week in Mexico – if the feature had rolled out a few days earlier, could it have flagged me as a foreign agent, trying to disrupt British politics by injecting technocratic centre-left ideas about incremental reform into the body politic?

And in some cases, the user may not even be aware that their traffic is being routed elsewhere.

For example, historically I think some UK train services have routed their wifi through Sweden, as that’s the home of on-board wifi provider Icomera. Or if you have to connect to a VPN at work, your traffic might be sent to corporate headquarters first – making your Twitter usage appear as though it is coming from head office, wherever in the world that is.1

And there are countless other potential points of confusion too. It could be something as simple as a given Twitter account using a social media management service, like Hootsuite, to schedule posts on their behalf – with the Hootsuite bot posting them from whichever country it is based in, and not necessarily the user’s home.

Or perhaps it could simply be the case that the geo-lookup table that Twitter is using to determine the location of each IP address is either wrong or not up-to-date.2 After all, an IP address does not permanently map to specific users like a phone number, or to specific locations like map coordinates.

There are also reasons to be sceptical of the user’s app store as a source of truth too. This is because it’s technically possible to change your location or the region your account is based in, in your phone’s settings. In fact, I’ve done this before, during the glorious summer when Pokémon Go was first released.3 Back in 2016, the US app store received the game a week before the UK, but I was so excited to play that I actually created a second, American Apple account so I could download the game to my phone, even though I’m based in Britain.

And then there’s my final reason for scepticism. Do we actually trust Twitter’s ability to engineer this to work reliably, so quickly?

We know that this feature was rushed out. Bier literally said “give me 72 hours”, and turned around the feature in mere days.4 So has geolocation been robustly tested to ensure it is reliable? Does Musk’s breakneck “extremely hardcore” approach to Twitter development have a good track record? It’s strange how some of Musk’s loudest detractors are taking this new feature at face value, without taking even a moment to sanity-check it, now that the app is reinforcing their priors.

Trust, but verify

This all said, I think the biggest reason for scepticism of this feature is that there are already plenty of documented examples where the geolocation is inaccurate.

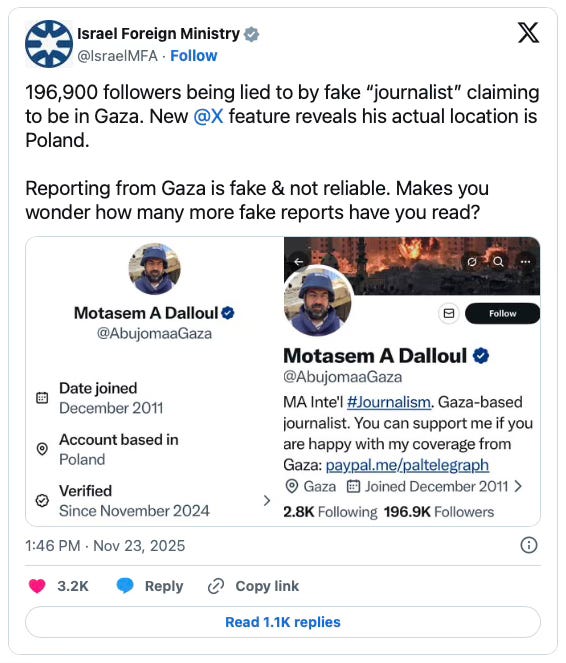

For example, my friend Rob Manuel, the hero behind Fesshole and B3ta, has already noted that the Twitter accounts for two of his projects have been erroneously placed in the United States and Germany. Similarly, there has already been controversy over a Gaza-based journalist’s account, which reportedly claimed he was based in Poland. He has subsequently posted a video of himself in Gaza, proving otherwise, but not before the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs used the new feature to try and discredit him.5

I’m sure in many cases, it could be possible to construct a reasonable explanation for these discrepancies. But the bottom line is that this is clearly not reliable enough.

I want to be clear. I don’t think this is like the spurious claims about Twitter bots I debunked a few years ago. I would be more surprised if all of the geolocations turned out to be total nonsense, because foreign actors clearly have strong incentives – either politically or financially (via Musk’s revenue share system) to essentially meddle in western politics.

But this isn’t my point. My point is that we can’t be confident that what we’re seeing is right. Somewhat unhelpfully, the geolocation feature has collapsed down a lot of complexity and ambiguity, and paints a false picture of certainty.6

And what disturbs me is that because this time the evidence appears to satisfy our priors, how quickly we turn off our critical faculties. This is even true for BBC Verify, which in this piece bafflingly doesn’t appear to actually… verify… anything, saying that “BBC Verify is not able to independently confirm the information X provides about each account.”

So this is all to say that, though I’d like to think this feature could make it easier to identify dodgy accounts, I think we need to set the credibility bar higher. When something seems too good to be true, that’s when we should be most sceptical.

If you enjoy nerdy, sometimes mildly contrarian takes on politics, policy, tech, media and more, then subscribe (for free!) to my newsletter!

Amusingly one source of confusing geolocation could be Elon Musk’s Starlink, as traffic is routed from satellites in Low Earth Orbit to ground-stations based in different countries.

In retrospect this was probably the last gasp of techno-optimism, before the anti-tech vibe shift. It makes me sad there’s never going to be a cultural moment like it again, when you could walk through London and see groups of people stopping at PokéStops and collecting Pokémon together.

The feature had apparently been in development since October, but it isn’t clear how ready it was before he hit the “go live” button.

Obviously citing example from the single most contentious topic on the internet is a dangerous thing to do. My point here isn’t to argue about the credibility or not of his journalism – I’m unfamiliar with his work. My point is that it is true that, contrary to Twitter, he is actually, for real, based in Gaza!

This is a weird metaphor but I think it’s a bit like how polling data maps on to FPTP. Most of the time, it is a useful proxy – as a party that polls well will usually win the highest number of seats. But there’s still a significant chance of something weird happening!

Good post. I think that yes, geolocation is hard, equally as you point to, it would be odd that bad actors and states wouldn't try to influence or manipulate using these platforms when they've done espionage and all sorts for years (what do you mean Bond is a movie?). I would say I don't think this story should be framed as Trump vs everyone else. If you look at who has been revealed as not where they seem, it cuts across left/right, populist/not populist, and all the geopolitical hot spots. Pro and anti-brexit and so on. Another example are Scottish Nationalists - some of the nosiest accounts first went quiet after the attack on Iran back in June, and when it was revealed on X that their locations were not in the UK - well, 2 + 2 does more than likely equal 4 in this case.

The which app store marker is stickier than IP geolocation though. You typically need a payment method from the country you are switching to: https://support.apple.com/en-gb/118283