Making London transport free is basically unworkable

"Fare Free London" is an appealing idea but a silly thing to campaign for

POD! On a blockbuster episode of The Abundance Agenda this week, Martin and I talk about the BBC’s pro-NIMBY bias, why it’s time to reboot Eurostar services in Kent, we catch up with Alistair Strathern MP and the mysterious case of Old Bridge Way, and we speak to author Sally Gimson about her new book, Off The Rails: The Inside Story of HS2. Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or Substack.

“Londoners need free public transport to reduce inequality and get polluting cars off the road, Transport for London (TfL) has been told,” according to the BBC’s Local Democracy Reporting Service last week.1

Unusually, the story doesn’t appear to be tied to anything of substance. Unless Google has defeated me, there was no committee hearing, no think-tank report, no protest, and no one important or noteworthy appears to have newly endorsed the idea.

Though I suppose after weeks of breathless reporting of a few hundred racists protesting asylum hotels, I guess I shouldn’t be surprised when a story is conjured out of nothing.

Anyway, so who has been telling TfL that London’s Tube and buses should be free? The answer is the campaign group Fare Free London (FFL). I’m guessing they persuaded the BBC journalist to write about them in the news desert of August, and then got lucky as the story was then syndicated by other outlets such as the Standard, and Yahoo, and it was picked up for a rewrite by Time Out.

Regardless of how the story happened though – making public transport free is an idea worth discussing because it would conceivably support two very righteous causes: It would make travel more affordable for the poorest in society, which could connect people to new opportunities for work and support. And it could help us achieve our climate goals, as it would in theory make public transport a more attractive option compared to taking a car.

These are obviously both very laudable aspirations. But there’s just one problem: the idea of making London’s public transport free for everyone is almost completely unworkable.

Like nerdy deep dives in politics, policy, infrastructure, transport, media and other stuff? Then make sure you sign up to get my newsletter directly in your inbox.

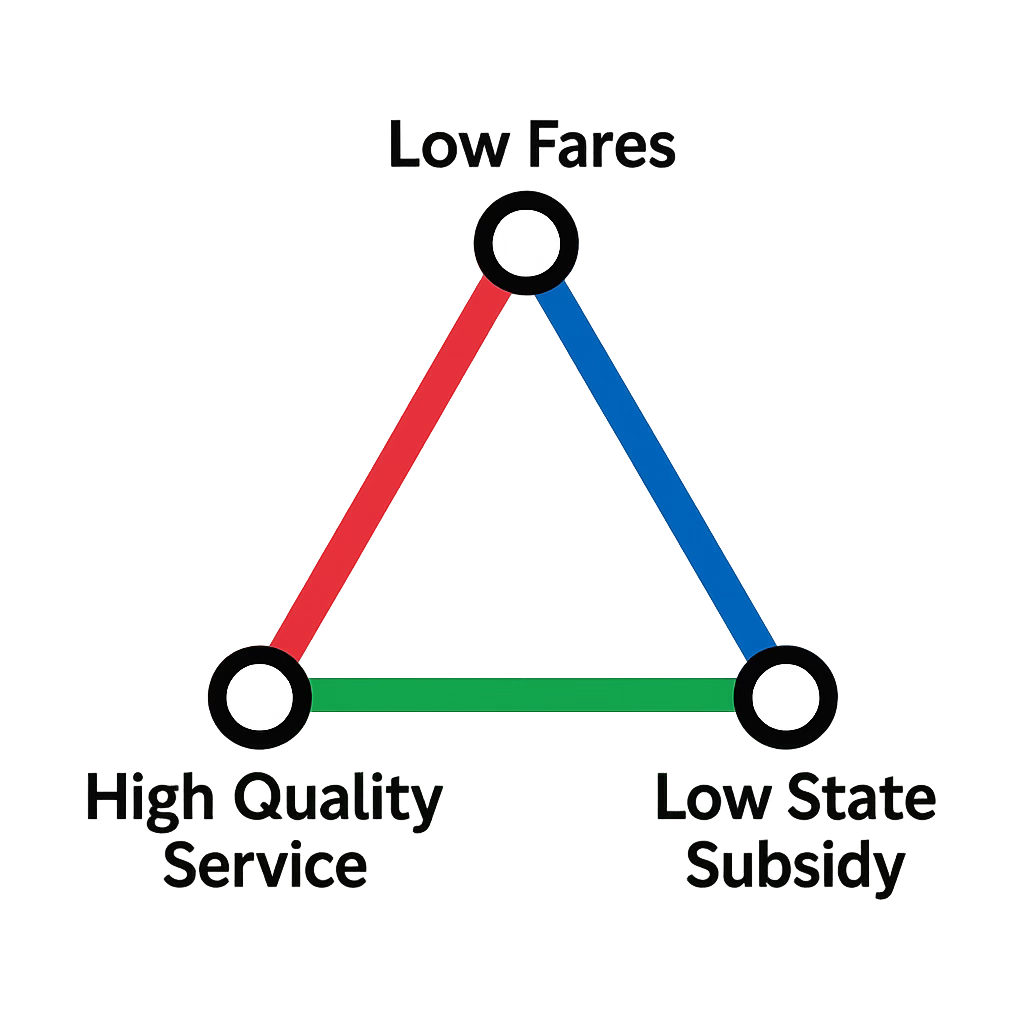

The ticket price trilemma

Let’s start with the fundamental ‘trilemma’ of public transport pricing. In an ideal world, we would want the Tube and buses to have three things: Low fares, a low subsidy from the government, and a high-quality of service – think things like trains that run regularly, buses that don’t break down, and so on.

All three are desirable, but the problem is that we can only pick two.

This is because it’s basically impossible to have all three at the same time.

If we reduce fares, and services are not subsidised by taxes, then we won’t be able to run as many trains or buses, or will have to make other compromises – like reducing maintenance. We’ll have to reduce service quality, in other words.

However, alternatively we could reduce the state subsidy and maintain a high-quality service – but this would necessitate hiking fares to make up the difference. And incidentally, this is actually the current TfL funding model, which has been in place since 2018 when the Tories cut the £700m of direct subsidy that Westminster used to hand out. At the moment, TfL has to pay its operating costs almost entirely by itself.2

So what about the third option, which is closer to what FFL wants? If we reduce fares – or remove them entirely – and if we want a high-quality service at the same time, then the government needs to basically pay for services from our taxes instead. Hence, the unwinnable trilemma.

Of course, in real life, the story is slightly more complicated than this. We can, for example, strike a balance between these three poles – which is why, for example, TfL has increased fares above inflation, and shaved down the frequency/extent of some central London bus services to try and make the sums add up.

Then there are a few other sources of cash for TfL: there’s commercial rent revenue from shops in TfL stations, income from advertising on the London transport network, and so on. And TfL even receives a cut of the business rates paid in London – which raises about £2bn. That’s not nothing, but is essentially just another form of state subsidy from taxation.3

Fundamentally then, the trilemma remains. And it is important context, because it reveals why making public transport free would be so difficult. Because if we did it, then TfL would need to find around £5.7bn, based on this year’s expected passenger revenue.

And even if you deduct the 6% or so4 that is spent on revenue collection (ticket barriers, Oyster cards, and so on), that’s still more than £5.3bn you’d need to find… every single year.5

Taxing questions

To be fair to FFL, they readily admit that funding is the crucial problem with their idea. For example, in this leaflet, posted to their website, they correctly admit that fare revenue amounts to somewhere between £5bn and £6bn every year – and then explain how they’d plug the gap:

So they’ve been thinking about it, at least in the back-of-the-envelope sense. It’s just the problem is that I don’t think any of the ideas listed above would actually work.

Though that’s not to say some of them don’t sound like good ideas. Let’s go through them.

First, FFL proposes giving TfL land and development rights around stations, so that when the land is developed, it can take a share of the profits.

This is an excellent idea – and it’s actually something that TfL is already doing. For example, the car park at Cockfosters station at the end of the Piccadilly line is currently being developed into 350 new flats. And over in Edgware at the end of the Northern line, there’s a monster redevelopment happening around the station.6

So I would genuinely love to see more of this. I want a cluster of skyscrapers surrounding every Tube station on the network, each containing plenty of new flats.

The problem with using this to plug the fare gap though would be that, well, eventually TfL will run out of land to sell or develop! Which is a huge problem if the idea is to use the cash to pay for operational spending, as the £5.7bn hole that TfL would need to fill wouldn’t just be a one-off – it’d need to find that much extra money every year.

This is also why another of the ideas above – land value capture – doesn’t really work for this purpose either. Don’t get me wrong, I literally wrote last week about how the Bakerloo extension could be funded via land value capture. But it only really works for capital spending, as you only need to pay to dig a tunnel once, whereas Tube station staff for some reason insist on being paid a salary every year.

Then we get to the other ideas, which are all variations on raising taxes in different forms.

For example, one is to impose further taxes on fossil fuel companies, and to be fair there is a clear precedent here. After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the ‘energy profits levy’ was imposed on fossil fuel companies to capture some of the windfall from energy prices shooting up. In 23/24 it raised £3.6bn, which is about half what TfL needs, so maybe we can use it to get a few lines up and running?

Unfortunately, there’s just one problem. Let’s imagine that we hike the windfall tax even further to pay for TfL. Leaving aside the broader economic consequences of doing so, isn’t it FFL’s plan that… we should stop using fossil fuels anyway?

As I’m sure the campaigners recognise, in the medium-term future either North Sea fossil fuels will run out, we’ll switch to renewables because they are cheaper, or the government will restrict us from burning oil and gas for Net Zero reasons – which will mean that tax revenue from fossil fuels will fall to zero. So how are we supposed to pay for free London transport then?

The next tax idea is a ‘Robin Hood’ tax on financial transactions – which is an idea that has been occasionally proposed in the years since the financial crisis.

Here, I’ll happily admit that I’m not an economist so I’m reticent to wade in on the broader macroeconomic consequences. But I guess the one thing I’ll note is that typically the reason these proposals go nowhere is because for it to work we’d need to coordinate the imposition of such taxes with other Western countries – otherwise it could lead to capital flight, which would be economically damaging.

And this brings me to the overall political plausibility of the ‘ask’ here.

Whether it is imposing a Robin Hood tax, or – as per the final suggestion7 – reallocating existing government spending to pay for the Tube and London buses, I just can’t see this as anything other than disastrous, as TfL would find itself much more at the mercy of other political priorities.

Does London really need that many buses, when the money could pay for NHS nurses instead? Why don’t we reduce service patterns and cut taxes instead?

That’s why, fundamentally, I think it is politically a good thing that TfL, at least to an extent, has the ability to mostly pay its own way – as it keeps services out of the hands of politicians in Westminster who may not have interests that are aligned with London’s commuters.

The one good idea

Sadly then, it appears that FFL hasn’t done much work on the ‘how’ question, though it does offer one other plan – of sorts – beyond the leaflet above.

On the website, there’s a button labelled “How to pay for it? Strategy and thinking”, which links to this essay by transport consultant Pearl Ahrens, who is involved with the campaign in some capacity.

Unfortunately though, her essay doesn’t offer many answers either, amusingly saying at one point that:

“[W]e’re also not directly talking about how to fund it, because it’s not the service users’ responsibility to work out how to fund public services. That’s the politicians’ job.”8

So good luck to the politicians I guess.

However, luckily Ahrens actually does go on to at least pitch a couple of other ideas for funding, and honestly, if free public transport is the goal I don’t think they’re that bad. In fact, I actually think one of them is almost persuasive.

The first is that we could pay by introducing road pricing. This is something that we’re going to have to do anyway, so you can at least vaguely imagine how prices could be set high enough to raise the extra £5.3bn. Though again, this would probably be quite a tricky argument to make politically.9

Then there’s the second idea – which is also suggested on the leaflet above about taxes on companies.10

Specifically, this is an argument for giving London fiscal autonomy – which is exactly what I advocated last week: the idea that London should be able to raise its own London-specific taxes.

Ahrens argues that if London could raise its own taxes, it could “make council tax more progressive and raise more money from the wealthy”, or “implement a small payroll tax”.

And there’s actually precedent for the latter. Ahrens cites research by the Centre for Cities from a few years ago, which points out that half of Paris’s public transport revenue comes from local taxes charged on companies that employ over 11 people. And that if we were to implement a similar levy in London, it could bring in around £1bn, with a 0.6% contribution from London’s gross wages.

So to do a crude back-of-the-envelope calculation, that would need to be a tax of 3.18% on gross wages to raise the required £5.3bn for all of London’s transport. Which would mean that the employer (not the employee) would pay an extra £63.60 per month for someone earning £24,000 – or £132.50 per month for someone earning £50,000.

Just to put this in context, imagine someone was commuting every day from Zone 4 to Zone 1 – that would cost about £240 per month on the Tube, or £94 per month on a bus.

And this is what shocked me researching this piece. To be honest, I went in fully expecting to shit all over the idea of free public transport – doing my usual ‘centre-left guy who punches left’ schtick.

But this comparison gave me a moment’s pause. Because I think if you squint really, really hard, you can almost imagine something like this being a plausible way to pay for a Fare Free London.

If the levy was imposed by the Mayor of London, you’d have an alignment of incentives around using the cash raised to pay for transport, and both the burden and the benefits would fall directly on Londoners, not the wider country. And even if wages fall as the additional payroll tax is passed on to employees, in aggregate many people would benefit by not having to pay for their commute.11

It still won’t work though

This all said, even though I’m apparently more left-wing than I expected to be, there are still a million reasons why I don’t think removing fares would actually work in practice.

The first reason is real world politics. If removing fares wasn’t done in tandem with fiscal autonomy for London, as described above it would leave London transport at the mercy of the government in Westminster. And that would be bad even if it was a Labour representing Zone 2 in charge, let alone, say, a Reform government that needs money for its army of immigrant-persecuting stormtroopers.

But even if London got its fiscal autonomy and the fare free policy was implemented with a very London-specific payroll tax, it’s still easy to imagine a tonne of problems.12

For example, at the moment the Tube is already running wildly over-capacity on most lines. That’s why during peak times, sometimes stations have to close to prevent overcrowding. And if there were no fares, this problem would become even worse, as TfL wouldn’t have the ability to ration services as it does now with on/off-peak pricing.13

And similarly, removing fares would likely increase passenger demand. Great in principle, as it means more people getting around and doing more stuff – but in a capacity-constrained system, there are fewer places for that demand to go. TfL could run more services or build more capacity – which would be great – but that would then increase the amount of money that TfL would have to either beg the government or tax Londoners for.

Then there are the problems with the idea that are more about principles.

For example, the question of who should be paying. London obviously receives many visitors who live outside of the capital. As things stand, they buy tickets and help fund the transport network’s operations as they use it, but if fares were free, they would be freeloading on London taxpayers. Should I, as someone who lives in North Kent but regularly travels into London, also be taxed? What about the 20 million tourists14 who visit London every year?15

Then there’s the social justice reality. Sure, removing Tube fares would be a good thing for the poorest in society – but wouldn’t it also be a massive bung for millions of middle-class commuters who can afford to pay their own way?

And anyway, given how precarious TfL’s finances are – aren’t there more targeted forms of support available for the people who need it?

For example, there’s already a 50% Jobcentre Plus discount for job seekers using the Tube, and there’s a 50% discount on buses and trams for certain people on Universal Credit. So instead of doing something wildly impractical like eliminating fares altogether, why not argue instead that these schemes should be broadened out? Why not extend the Universal Credit discount to the Tube, for instance? Or make the Tube free for those specific qualifying people?

So I guess where I come down on this is strangely a little more open to the idea of a Fare Free London than I was before I started researching it. But I still think that it is ultimately unworkable because after all, you can abolish fares – but you can’t abolish costs.

Phew! That was a long one this week! If you enjoyed reading this please support my writing by subscribing for free to get my newsletter direct to your inbox. Every week I wrote about politics, policy, transport, infrastructure, tech and other nerdy stuff. So if you’ve read this far, you’ll probably like it.

We actually talked about the LDRS and its… interesting choices… on this week’s episode of The Abundance Agenda.

Rachel Reeves did throw TfL a one-off payment of £485m for this financial year, but this was for capital investments like buying new trains, not paying the salaries of bus drivers.

Those Elizabeth line moquette socks you bought at London Transport Museum are also helping to pay for the Tube.

This is actually a pretty optimistic estimate from this 2017 McKinsey report. Back when it was written, revenue collection was where 15% of the cash went – but it was expected to drop to around 6% once everyone has switched to contactless cards and mobile payments, which presumably has now mostly happened.

To put this further into context, this is roughly equivalent to having to pay for a new Elizabeth Line once every four years. Forever.

There are various other schemes across the capital, including one in High Barnet that is currently being consulted on, and is the subject of a big pushback by NIMBY opponents. It would be a terrible shame if, say, readers of my newsletter were to email their strong support for the development to the consultation email address on their flyer…

I’m not going to take the “it’ll be good for the health system in the long run” idea seriously, because even if it is true (it might be), there’s no real mechanism to borrow against health outcomes 30 years down the line to fund operational spending today.

It also includes the sentence “By re-invigorating classical Marxist ideas of working-class control of the spaces and conditions of life, we want to shift people’s ideas of what is acceptable and possible and move closer towards a socialist horizon.”

I’m sympathetic to the argument made by the Policy Exchange, described in my road pricing piece, that to get away with the difficult road charging transition, it shouldn’t be linked to policies to shift us to public transport.

I didn’t mention it before, as I wanted to save it for this exciting reveal.

Though obviously just by changing the way the Tube and buses are paid for, it would obviously create winners and losers. Some people would find a slightly lower salary but free commute beneficial, others would find the trade works out badly for them.

And this is aside from the political problem for the Mayor of needing to sell the leafy, car-centric outer-London boroughs on paying a tax for a transport system they rarely use.

There are also lots of downstream consequences to puzzle through. For example, could it incentivise more people to move to Zone 6, spiking housing prices there? Why not live somewhere a bit leafier, with a larger home, if you can commute for free?

Technically this is a figure of 20 million ‘overnight visits’ per year – so it’s probably somewhat fewer individual people, but still – that’s millions of people and millions of journeys.

Even if we instituted a regime where only Londoners get to ride for free, and everyone else has to pay, then that will mean we’ll have to create and maintain a whole system of validating residency, performing checks and ticket barriers etc, which would add to the bill.

Fare free London may be a step too far but moving to a single transport zone for London’s tube and train system is certainly worth thinking about. It can be funded by a higher overall fare than the current one for the central Zone 1 and 2 ticket price.

Single city zone works in Paris, Berlin( effectively as it only has a higher zone to cover trips to its airport) and New York and reduces administration costs as there is no need to have staff on exit barriers at tube stations.

As London’s population moves/ is priced out of Zones 1 and 2 the current zonal system is effectively a tax on the poor and average in London and a bonus for tourists who rarely leave Zone 1. We already have a single pricing system for London’s buses and it’s about time we extended it to our tube and train system.

How did you know I would be wearing Elizabeth line moquette socks as I read this… :D