How to fix the New Statesman

In which I probably burn some bridges.

Twitter’s most underrated function is that it is a tool for social mobility.

After graduating into the financial crisis, I moved to London and I didn’t know anyone. My parents are not super wealthy, I went to a normal comprehensive school in the Midlands – and then to a post-1992 university. So when it came to getting a job and building a professional network, I was essentially starting from scratch.

But the one asset I did have was that I was a Twitter early adopter. Through the platform I discovered an entire professional world that would historically have been closed off to me, and as I followed journalists, politicos and other high-flyers, I was able to glimpse into their world, learn the industry gossip, identify the behind-the-scenes power-players and master the terms of art. Scrolling my timeline was like having a permanent spot at the water-cooler of London’s political and media elite.

Fast-forward through 17 years or so of intense tweeting and I’ve successfully carved out a freelance career as a professional writer and opinion-haver. I have a professional network and connections with people I’d never have had access to otherwise1. And I’ve even memed my way into meetings with important politicians.

So Twitter, in a very tangible way, has changed my life for the better.

However, it has also given me another super-power, which is more of a mixed blessing: I’ve become a real connoisseur of low-key Twitter beefs.

For example, one classic of the genre is the tension between former academic co-authors Rob Ford and Matthew Goodwin. After working together on Revolt on the Right, the key text in understanding the rise of UKIP, today they are more likely to be found subtweeting each other with barely concealed contempt2.

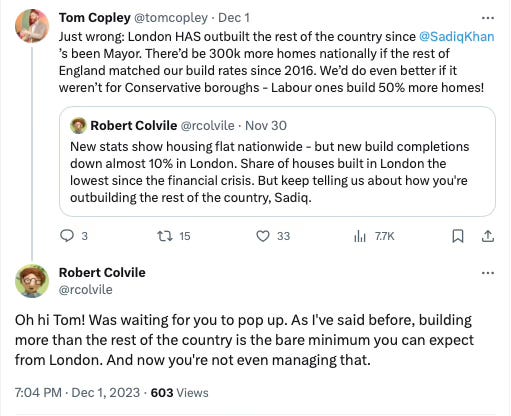

However, their beef is a bit too mainstream now, and I’m a hipster. That’s why my current favourite sparring partners to watch are Robert Colvile, the YIMBY director of the Thatcherite Centre for Policy Studies, and Tom Copley, the Labour Deputy Mayor of London with the housing portfolio. Each time new building data is released, you can pretty much guarantee the pair will be enjoyably raging at each others’ takes3.

And just in case you’re wondering, my favourite trans-Atlantic beef is between my close friend Nate Silver and the Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr, who used to work for Silver at FiveThirtyEight. Though they keep their subtweets broadly civil, there’s clearly some drama beneath the surface along roughly classical-liberal-versus-woke lines.

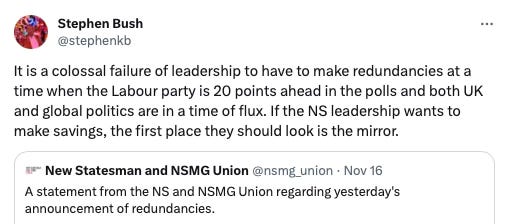

Anyway, I mention this because a couple of weeks ago, a significant drama-bomb was dropped by one of my favourite writers, Stephen Bush of the Financial Times. After his former employer, the New Statesman (NS), announced a round of redundancies he tweeted a stinging criticism of the direction of the publication, and accused its bosses of a “colossal failure of leadership”.

Ouch.

He has a point though. It is definitely weird that the NS, which is often described as the “Labour Bible” is struggling given that the Labour Party is in the ascendence.

I don’t have any inside information on exactly what has led to the redundancies4 but what seems to have gone wrong is that the 'international expansion’ strategy, which began 2021 with a bunch of expensive-sounding new hires, appears to have stalled.

I’m guessing by the upmarket rebrand that the management basically said “Try and be more like The Atlantic” – which has been a digital success story in the United States. But then it turned out that scaling a primarily British publication, with a British-sized budget, that only has brand value in Britain, has proven more difficult than hoped5.

As I say, this is just wild speculation – but that’s an explanation that would explain the redundancies.

So if this is the case, perhaps then it is time to pivot again to another strategy. The NS needs another new direction if it wants to be successful. And the good news is that I think I’ve figured out what that direction should be.

So read on as I dive in and explain how to fix the New Statesman – and risk burning a few bridges along the way.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Odds and Ends of History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.