The "BritCard" digital ID proposal is a good idea

Why I've changed my mind on ID cards

POD! On The Abundance Agenda podcast this week, I’m vindicated as Sizewell C is finally funded, and Martin digs into the economics of Small Modular Reactors. Plus we wildly speculate about the future of Northern Powerhouse Rail, and (whisper it) HS2’s northern leg. Plus we speak to Kirsty Innes from Labour Together about, well, what I’ve written about below! Listen on Spotify, Apple or Substack.

I’ve always found it surprising just how hostile many British people are to ID cards.

I say that as someone who has, over the years, been pretty sceptical of them myself, because I’m sympathetic to the well-rehearsed civil liberties arguments. It would be bad if the introduction of ID cards led to a “papers, please” society, where we need to show ID to perform trivial tasks.

But the British public? It’s strange that the idea of ID cards is seen by many in Westminster as politically toxic, because British people love a bit of petty authoritarianism. If something bad happens, whether it is evil killer dogs or Irish rappers with spicy lyrics, our national instinct is to respond with a cry of “ban it!”

I mean, look at how quickly we all got comfortable with the idea of lockdown. Now we’re five years on, I can safely admit that for those first few weeks of Covid, I was a bit nervous about the power of the state, and how unnerving it was that we all seemed weirdly fine with the government using its coercive powers to impose draconian restrictions on our lives, when there was no real guarantee life would ever return to normal.1

However, bring ID cards into the conversation and suddenly we remember how Britain is a great bastion of liberty and freedom, and digital identity is a database too far.

We saw this happen again a couple of weeks ago, when the Starmer-aligned think-tank Labour Together published a paper proposing the creation of “BritCard”, a new ID card system – with the big idea being that, if adopted, it would help tackle the problem of illegal migration.

The political upside for the government if it were to adopt the policy is pretty obvious. Such a system would give the government a positive story to tell on immigration, a policy area where the right has a natural advantage. The card – albeit not a physical card, but a digital ID on a phone app – would be a tangible way to show that something is being done. And hell, maybe the policy might actually achieve what the government wants, and help reduce net migration.

Unsurprisingly, though, the proposal immediately attracted critics.

The plan is “a grotesque example of state power,” according to my friend Ian Dunt, who argued that BritCard could be easily misused to persecute minorities. And lefty Labour MP Clive Lewis went even further, damning BritCard as “a repression ready, gift-wrapped surveillance state for Farage to pick up and run with.”

Ouch.

So I know what you’re thinking: What do I, the most important person in this debate, think about the BritCard proposals?

Here, I feel conflicted. When I told Ian I was writing this piece, I could see his face trying to compute which way I’d go on BritCard – as I’m both temperamentally pretty liberal, but on the other hand, I’ve been radicalised as a state-capacity guy who desperately wants a more capable state.

So which side do I come down on? I’m slightly surprised to say that I think I’m now on the side that thinks ID cards – or more accurately a digital identity system like this – is a good idea.

So I thought I’d explain why.

If you like nerdy politics, policy, tech, infrastructure, transport and media content, then subscribe to my newsletter (for free!) to get more of This Sort Of Thing direct to your inbox.

Rights and wrongs

The argument at the heart of the paper, which was written by Kirsty Innes, Morgan Wild and Laurel Boxall, is that the government should build a digital identity system to carry out the “right to work” checks that happen when you get a job, and the “right to rent” checks that happen when you rent a home.

These are legal burdens put on employers and landlords, to make sure that you have, well, the legal right to work or rent. And at the moment, the system for doing so is pretty messy.

If you’re a British citizen, it’s relatively straightforward for most people. You can just show them your passport – but not everyone has a passport. So you might have to use your birth certificate instead. Good luck digging that out of the back of your parents’ cupboard.

However, if you’re not British, proving your rights can be significantly more annoying. If you’re lucky, depending on the type of visa you’re on (or if you’re a settled EU citizen), you might be able to get a share-code from the GOV.UK website, which your employer or landlord can use to check your status. That’s relatively painless.

But if you’re unlucky, you might have to dig through reams of immigration paperwork, and use that as compiled evidence, and it is exactly as annoying as you imagine.

And these checks are not just frustrating for workers and renters, they’re a pain for employers and landlords too, and checks are often outsourced to third-party companies, adding more layers of bureaucracy.

So what the authors of the paper are instead proposing is that we replace these bureaucratic hurdles with what they call “BritCard” – a digital ID that is held in an app on your phone. Instead of needing to provide your new employer with a big pile of papers, you would instead simply display a QR code2 from your BritCard app, and your employer could scan it with a verifier app, which would give the green light for you to get to work.

And here’s the clever part about the Labour Together plan: Much of the technical infrastructure to actually build such a system already exists. We just need to use it for this new purpose.

The One Login foundation

I’ve written about One Login before. This is a common login system that will one day be used across nearly all of the government’s digital services – the websites you use to pay your taxes, claim benefits, update your driving licence, and so on.

As things stand, the system is still in the middle of a slow roll-out: It’s currently the login system in use for a bunch of niche government interactions like applying for an import licence or getting a fishing permit in Wales. But eventually (just don’t ask exactly when), the plan is for all of the really big government services to move over to One Login too – things like HMRC’s self-assessment tax return service, and the DWP’s Universal Credit system.

So it will (eventually) mean that you’ll only need to remember one username and password for almost all of your interactions with government – and your One Login will become more useful the more government services you interact with.

And crucially from Labour Together’s perspective, One Login already has a clever identity proofing system built into it. It’s slightly more complicated than this, but in principle it is designed so that, for example, once you’ve already proven who you are to, say, DWP when claiming benefits, you won’t have to provide the same credentials to DVLA when you register your car.3

Perhaps you can see why this system would make the perfect foundation of a broader identity system: Once One Login is in use across government, it will create a massive database containing literally tens of millions of verified people.

However, this isn’t the only component you need for an identity system. What about the “right to work” app that would be needed? What about the place where we can store and access our “BritCard” credential, should we need to present it?

It turns out this already exists too.

Enter the wallet

Later this month, the government will be launching the official GOV.UK app, with the intention that it will become the new centre of our digital interactions with government – a bit like how all of our healthcare interactions are being slowly piled into the NHS app.

One Login will (again, eventually)4 be an integral part of how the app works. The intention is that it will eventually evolve into what looks like – to the end user – basically Facebook but for your government interactions, where inside the app you can do whatever you need to, whether pay taxes, register a business or tax your car.

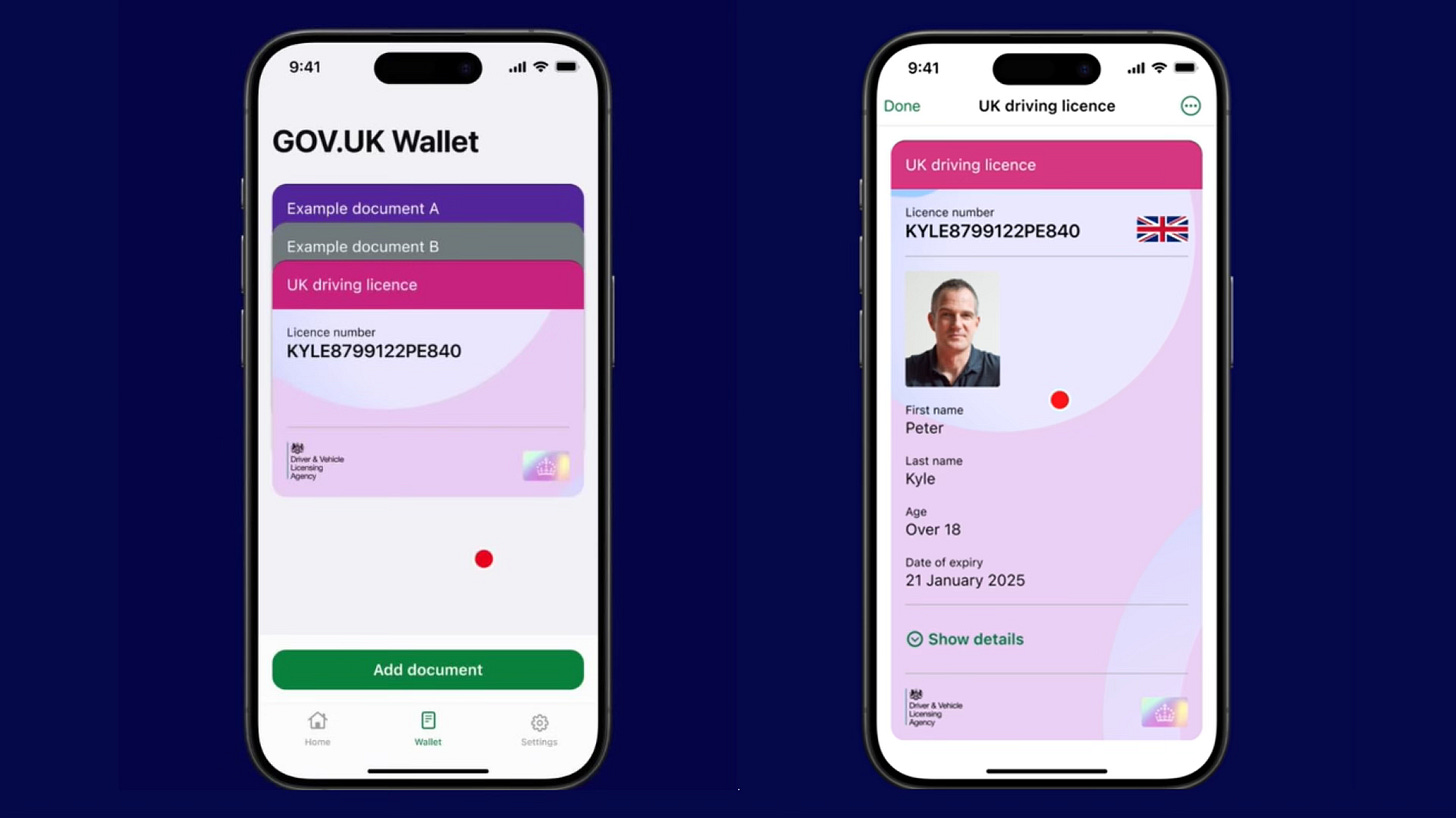

And though I’m not sure if it will be there at launch, or if it will come later, eventually the GOV.UK app will also contain a major feature called “GOV.UK Wallet”.

Functionally, this will work very similarly to the Wallet apps made by Apple and Google, which are digital repositories for your bank cards, loyalty cards and tickets. You know, like a real wallet.

Here’s what the GOV.UK wallet will look like:

The GOV.UK Wallet will do something similar to Apple and Google – but will be a place for storing government-issued credentials – which are a key conceptual building block in the government’s ambitious digital plans.

The idea is best described by digital government’s spiritual leader, Richard Pope, in his excellent book Platformland. “Credentials” – or what tech people might call “Tokens” – provide “digital proof that someone has done something.”

For example, when you pass your driving test, you receive a driving licence – a credential showing that you are entitled to drive. Later this year, you’ll be able to store a digital version of your driving licence in your GOV.UK Wallet – and it will carry the same legal weight as your physical card.

But the reason the government is creating an entire Wallet is because, when you think about it, the public sector issues tonnes of credentials like this.

For example, instead of needing a physical letter from a doctor to prove to DWP that you’re entitled to certain sickness benefits, (eventually) your doctor may be able to issue you with a digital credential that will prove you’re entitled, without you needing to reveal any personal medical information to DWP.

Or perhaps the wallet could hold a credential proving that your child is entitled to free school meals, or that you hold a blue disability badge.

And this is where BritCard slots in. Thanks to GOV.UK Wallet, BritCard wouldn’t need to be a whole new system – it could just be another credential stored in your wallet, and it could prove your right to work, right to rent, and act as a verified ID card more generally, for other situations when you may need to prove that you are who you say you are.

So I think Labour Together’s logic makes a lot of sense. The underlying systems to make BritCard possible – save for the specific links with specific visa and passport databases – have already been built. Though the government absolutely wouldn’t characterise it this way, One Login and Wallet take us most of the way to a system of digital ID as it is.

Do we really need this?

Since the paper was first published a couple of weeks ago, it has definitely proven controversial in the extremely niche community of people who care about digital government.

For example, my postcode campaigning pal, Peter Wells, took issue with Labour Together’s claim that BritCard could possibly have a “canonical up-to-date view of the set of people with the right to be in the country”. And Richard Pope, who I mention above, says there are “lots of sensible things” in the paper, but is nervous about how it flattens the concept of digital credentials into a singular ‘card’ metaphor.

And then there is the simple civil liberties point that, well, should the right to work and right to rent checks be carried out in the first place? Both are actually fairly new ideas – the former introduced in 1997, and the latter in 2016.

So why is now the moment where I have apparently taken the Blairpill on digital identity cards?

I think my view comes down to a couple of factors. First, these checks are not going to go away.

For as much as we may wish to have a philosophical debate about the surveillance state, and as uneasy as theses sorts of checks may make me in the abstract, the reality is that in the medium-term, it would obviously be politically impossible to remove them. It wouldn’t just be the Daily Mail kicking off – the only words we’d hear from the right until the next election are “Labour is soft on illegal migration”, and they’d have some credible evidence.

So given this reality, we may as well make these sort of checks easier to carry out. As the status quo isn’t that these checks aren’t happening – it’s that they are happening, and they are a nightmare.

I’m also sympathetic to the argument made by the authors in the paper that turns the “papers, please” criticism on its head – they argue (as does the political scientist Rob Ford) that having a digital credential proving your rights could protect you from the state, with the obvious example of this being the Windrush scandal, where dozens of long-term, legal British residents were wrongly deported because of a lack of paperwork.

As co-author Kirsty Innes told me on this week’s Abundance Agenda podcast – the problem with the “What about Farage?” argument is that if a future oppressive regime does come to power… well, there’s nothing to stop it from building an ID card system and abusing it if they wanted to – so it’s better to build a version now that has legal checks and balances around when it is used, and so that it is designed on a technical level, per the ideas of Richard Pope’s Platformland to give people better control over how their data is used.5

And she also makes a persuasive case against the Farage argument: that the way to persuade people that populist authoritarians are not the answer is to actually make government more functional, and work more effectively. Which is something that digital ID can help with.

So on balance, I’m inclined to take the pro-digital ID side of the trade-off. BritCard is a good idea – but we should always remain vigilant of the trade-off.

Subscribe (for free!) to get more of politics, policy, tech, infrastructure and media direct to your inbox!

And don’t forget to listen to this week’s episode of The Abundance Agenda, where we’re talking to Labour Together’s Kirsty Innes about, well, digital ID and the BritCard proposal! Listen on Spotify, Apple or Substack.

Oh, and if you’ve read this far you’ll definitely like this one I wrote too.

Something striking about the pandemic looking back is how little it changed about the world. If you’d have asked me in 2020, I’d have predicted that lockdowns would bring down governments, and that dictators would use the virus as a pretext to impose sweeping emergency powers. And though there was some marginal cases (such as perhaps Biden narrowly winning because of Covid), the world after looks… actually pretty similar.

Or use NFC, of some other mechanism of transferring data.

One day I’ll write an ultra-nerdy post about how One Login works behind the scenes, as it is designed in a super clever way, with different levels of confidence for different activities and different types of document.

The beta version of the app is little more than a directory of links to pages on GOV.UK, so I’m not sure if the initial version will let you (make you?) login.

One commonly cited example of this is Estonia’s “X-Road” system, which lets citizens view a log book of whenever different government departments and agencies have looked at or forwarded their data.

I'm not sure if the various papers mention this, but it would also make automatic voter registration easier.

After emigrating to a place where a physical ID card is mandated, and which now has an online counterpart with all the supporting state-managed auth and validation services, it is obvious to someone from the UK and familiar with the mish-mash of ways you have to 'prove x to y' just how many issues it solves, and staggering there is so much resistance to it in the UK.

And as a brexit evacuee, I can prove my rights and entitlements to anyone here in seconds, and I know that this is not a privilege enjoyed by those who have moved in the opposite direction.

State surveillance/overreach etc.? I'm far happier with the state managing this kind of thing than an opaque collection of commerical credit scoring/KYC/AML businesses, many US-owned, which underpin a lot of the 'prove who you are' services. This hacks a lot of their business off at the ankles, and that, frankly, is a good thing.