E-scooters are good and Britain should legalise them

You can't uninvent the wheel

Phew, apologies for the long gap between posts. If you’d like me to write more regularly, please consider pre-pledging a subscription for if I ever launch a paid tier. Writing essays like this is one of my absolute favourite things to do, but they take several work days to produce. So I need to convince myself there’s a business case to do so before I make the leap to paid.

A note on Notes: Like everyone else, I’m giving Substack Notes a try, so don’t forget to jump in the lifeboat and go follow me over there, just in case Elon does finally ruin Twitter.

BONUS WRITING: Over on TechFinitive, I’ve written about why I think ChatGPT is the real deal, and contrary to the naysayers on Twitter is more than just “fancy autocorrect”. In fact, I think it is already changing the world.

At the start of lockdown in 2020, I made one of the worst spending decisions of my life. I bought an e-scooter.

You know the sort I mean – a push scooter with an electric motor and a battery. The sort that has become almost ubiquitous in recent years as the go-to mobility solution for your local yobs.

I thought that I was an incredibly savvy shopper. With the onset of the pandemic, the London Underground and the buses were out of bounds. My thinking was that with a scooter I’d still be able to experience the area beyond my immediate vicinity. Perhaps it would be a boon to my mental health during the brief times of day we were permitted to leave our homes.

And less sympathetically, having tried scooting on holiday in various European cities, I know how enormously fun they are to ride.

However, there was just one problem: Privately-owned scooters were, and today remain, illegal.

Because they have a motor they are not counted as pedestrian traffic, so can’t be used on the pavement. And it’s not possible to get a licence, or obtain insurance to use them on the road. So effectively, while it is legal for shops to sell scooters, you’re restricted to riding only on private land. Which basically defeats the point.

There is, to be clear, a quasi-exception: In some cities and towns, operators like Lime, Voi and Bird run government-approved hire schemes on a trial basis, which are designed to work more like Boris Bikes in London. But riding a privately owned scooter is still a nationwide no-no.

I knew this when spending the money back in 2020, but I was making a gamble. I assumed that as part of the government’s emergency suite of Covid measures, scooter legalisation would be a no brainer – a way to reduce congestion without relying on public transport, following the same logic that led to the various emergency cycle lanes that were installed around the country. What made my plan truly a work of genius was that I smugly assumed that when the post-legalisation sales rush arrived, I would have beaten the queues, and that my scooter would be ready to go from day one.

The only problem was that the legalisation never happened.

To this day, my Ninebot Max G30 remains in my garage, collecting dust1, because I’m probably the only scooter owner in the country who is actually following the law2.

And three years on, I think this is crazy. Even though we’re functionally out of the pandemic now3, I think the case for legalising scooters is stronger than ever. So here’s why the government should hurry up and legalise private e-scooters.

I suspect this might be my most controversial post yet. Forget culture war fodder like wokeness or trans issues, I think I’m going to make literally everyone unhappy. But hey, if you enjoy these sorts of mildly contrarian takes, why not subscribe (for free!) and get them directly in your inbox?

Winning a zero-sum game

The reality is that in cities, there is only finite space between buildings and the places people want to go, so the challenge for transport planners is how to maximise the space so that the most people can get to where they need to be in the most timely manner.

Obviously there’s lots of variables at work here, and a number of different policy interventions that could speed things up.

Increasing the speed limit would increase the throughput of cars. Congestion charging would reduce the number of cars entering a road or area in the first place.

One transport planner even told me once about how things like the allocation of parking spaces can also be used as a very sneaky way to manage demand: If finding a space is going to be nightmare, you’re more likely to catch the bus instead.

But each of these policy interventions comes with trade-offs. Higher speed limits makes the roads more dangerous, congestion charging makes visiting more expensive, and so on.

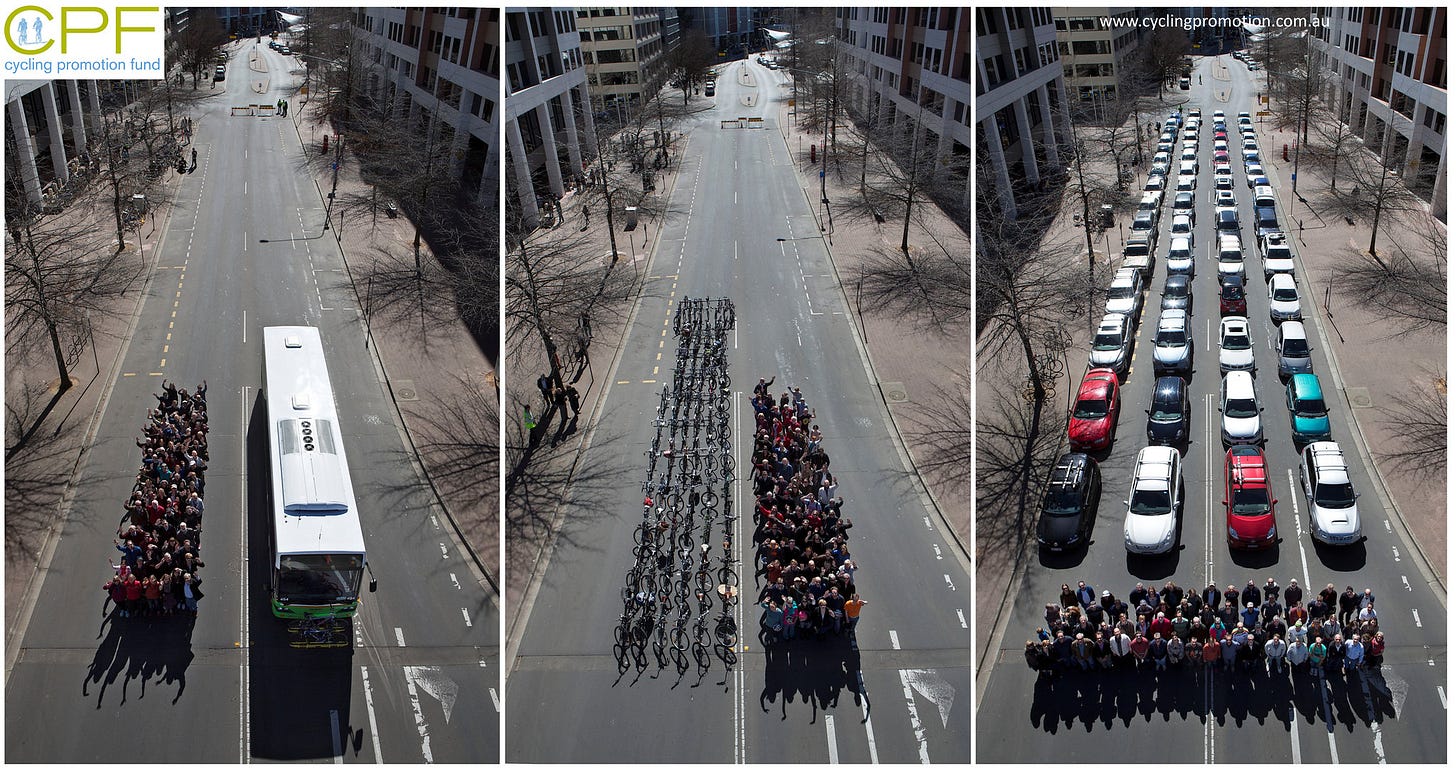

These trade-offs are, however, a downstream consequence of the fundamental truth that how we allocate road-space is effectively a zero-sum game4. It's is why this clever image, which has become a bit of a cliché in transport circles, remains incredibly compelling:

What it shows is how 69 people can fit on the road: If they all use their cars, it takes up tonnes of space and congests the road. If they all take the bus, you can pack people in really tightly, and if they use their bikes – while not quite as compact as a bus, it still uses significantly less road space5.

This is why pretty much the modern consensus when it comes to urban planning is today the reverse of the 1960s approach of bulldozing large swathes of cities to build motorways: Instead, the objective is to reduce the number of cars on the road. The more cars we can remove from our streets, the easier it is for everyone to get around: There’s less congestion, and it creates a virtuous cycle where with fewer cars, buses and other modes can get around faster – making other, usually greener, transport options an even more attractive option6.

So why am I so bullish about e-scooters? Aside from my vested interest in the £700 of sunk costs currently sat in my garage, I mean.

Essentially, e-scooters are almost perfectly optimised for the task of reducing car usage. They take up much less space, and are physically small in size – perfectly designed for getting around cities.

There’s some evidence that this is the case too. A study on the rental scooter trials commissioned by the Department for Transport discovered that “frequent users (who rented e-scooters at least three or four times a week), were more likely to have travelled by bus or car/van in the absence of e-scooters.”

So it appears that scooters really are removing cars from the road7.

Scooters also offer (whisper it) a number of advantages compared to cycling, the most obvious point of comparison. Primarily, scooters don’t require as much physical effort to operate, so you don’t end your ride a big sweaty mess. This is great if you’re a big fat bloke like me, or if you want to get to your important business meeting without looking like a wreck. And because scooters are smaller, they are also better suited to multimodal travel, such as taking the train and then scooting the last mile to work.

Also, and just to make sure any cyclists reading are absolutely furious by now: I realise this is subjective, but there’s also less bullshit associated with scooting: What cycling people don’t tell you is about all of the special clothes you need, or how much maintenance your bike requires to remain functional8.

Now don’t get me wrong, cycling is an essential part of the transport mix9. Cycling is brilliant, and more people should do it. I myself am a cyclist. But the point is that e-scooters lower the barriers to entry to non-car travel, and further expand the pool of people able and/or willing to travel without using a car.

And if that can happen, that’s a good thing that will make our cities and towns work better.

Downstream consequences

I think there could be other positive downstream consequences of scooter legalisation too. There’s obviously the climate impact. Scooters are zero emissions, so the more journeys that can be switched from car to scooter, the better it is for the planet.

But I think scooters on the roads could reshape our urban geography for the better too.

At the moment, when local authorities are weighing proposals to build cycle lanes, they inevitably face significant local opposition from motorists incorrectly worrying about congestion and melting down in their local papers over the prospect of possibly losing a few parking spaces10.

The problem is that for a cycling network to be most useful it needs to be just that: A network. Fundamentally, if you’re not a lycra-clad maniac, you need your whole journey to work to be safe, not just one bit of it. But due to the way society works, instead of building a network in one go, a piecemeal approach is how local authorities do it.

So how would legalising scooters help? Essentially they would be another thumb on the scale in favour of building segregated cycling (and now, scooting) infrastructure. If more people want to use this infrastructure, it makes building it more politically compelling for councillors to approve. So scooters could help us nudge a little further away from the tyranny of the car.

But this isn’t my only pet issue that scooters are a magic bullet for solving.

No, sadly legalising scooters will probably do little for liberating the Postcode Address File. But I’d bet scooters could make a small difference in the housing crisis.

If you imagine the plausible commuting radius from every train station and town centre in Britain, scooters increase the range. Homes further away from stations suddenly become more attractive, developments on the urban fringes become slightly less remote11.

Obviously it would be hard to measure the specific role scooters play in such things, but if you imagine calculating “viable housing locations” as a massive equation, making a place more accessible obviously helps.

My hidden agenda here is that I know this would be very specifically true for my own personal circumstances. Now that I’ve moved to the suburbs, the nearest train station to my house is about a 25 minute walk away – or a five minute drive. Because this isn’t London, there is no bus service worth relying on. And because I am human and not an AI trained on handwringing Guardian articles, this means that 99% of the time I’m driving to the train station – with all of diesel emissions12 and congestion that entails (not to mention the need to park a sizeable vehicle, further cluttering up my destination).

So you can imagine just how infuriating it is to have a scooter in my garage, which could get me there in five minutes but which the law says I’m not allowed to use.

But what about the arseholes?

Now I know what you’re thinking and you’re right: Literally 100% of the people who currently own e-scooters are arseholes. You’re right. I’m not going to deny that.

You’ve probably got a story about how you were almost knocked over by a young hoodlum who was riding on the pavement. As things stand, scooters are a menace to society – so what sort of sicko in their right mind would want to make them legal to ride?

I think the crucial way to think about this – and this is an argument scooter campaigners have been making for some time – is that it is like drug legalisation.

Obviously, drugs can be terribly destructive and have real negative externalities, but it’s broadly accepted by experts, if not politicians, that the best way to deal with them is to make the less dangerous drugs legal.

Legal drugs makes treatment easier, as it means that a user doesn’t need to get wrapped up in the legal system or risk having their career as a promising Tory MP derailed13. And it means that the sale and use of drugs – which is virtually impossible to prevent – can be regulated, taxed and made less dangerous.

In the same sense, if privately-owned e-scooters were legal, the government could enforce certain safety standards (eg, the 15.5mph speed limit), oblige riders to wear helmets, or even do more heavy handed things like first earn a licence to ride, register their scooter or obtain insurance.

And perhaps more importantly, it would mean that local authorities could justifiably adapt our cities to reflect the reality that e-scooters are here and are not going away, by building the cycle lanes and other infrastructure that will enable scooters to live more harmoniously alongside cars and pedestrians. Train stations and transport hubs could even build specialist parking for scooters, and transport planners could factor scooters into “last mile” plans.

And finally, what of the arseholes? Even if we redesign our cities and make other interventions, there’s always going to be some miscreants, right?

Well, I can see why they did it this way, but I wonder if the current e-scooter trials were actually the wrong way to go about winning public support for scooting, because they inadvertently exacerbate negative attitudes. As while the trials are demonstrating the technology and providing real world data on how people interact with them, they also capture several of the negatives of scooters, without some of the positives of private ownership.

For example, two recurring complaints with the trials is that riders leave their scooters strewn across pavements, and that when riding, they may behave dangerously. Those are probably some of the reasons why Paris, a scooting early adopter, recently voted to ban rental scooters.

But neither of these factors would be present if scooters were privately owned like (most) bikes are: Private owners would obviously not discard their expensive scooters carelessly, and they would be, on average, better trained and more experienced at riding than casual renters. They would also be more likely to own and wear a helmet and other safety equipment.

In a sense then, a private scooter is like a regular drug user quietly smoking a joint at home of an evening – something they will have learned to do relatively responsibly. And a rental scooter is like if a local authority was to set up crack-pipes on street corners, and offer a toke to inexperienced commuters on the way to work14.

And as for poor behaviour? I’m not convinced that legalisation would make a massive difference to this. Right now, scooters are available in shops and are easy to buy, even though they remain illegal. And my hypothesis is that basically, any miscreants who want a scooter already have one, and that the Venn diagram of “scoots recklessly” and “follows the law regarding the use of e-scooters on public highways” is very small indeed.

If legalisation happens, the next wave of riders is, in my view, likely going to be the boring normies: The older people, the commuters, the dullards who will actually wear a helmet. And who, almost by definition, are more likely to ride more sensibly15.

Poverty of ambition

Ultimately, I think this argument goes back to one of the major themes of my Substack: That we actually need to build stuff. E-scooters are a new thing. They are only possible because the smartphone revolution has massively improved battery density, and made components available at reasonable prices.

Technological progress has handed us this almost magical device, capable of reducing congestion and making cities more liveable, without either restricting our mobility or releasing any carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This is a high where we’ll wake up the next morning, not surrounded by vomit and regret – but with a better society.

And more importantly, like drugs, whether we like it or not e-scooters are a reality and the genie is out of the bottle. The report mentioned above reckons there could already be as many as 750,000 in use privately in Britain. So we need a policy that actually reflects this reality.

So my point is simple: It’s time to end the prohibition on private e-scooters.

To make it happen, as I understand it, this will require Parliament to vote on it. Legalisation can’t be achieved through Ministerial diktat. And having spoken to people who actually know what they’re talking about, I understand that it is something the government still plans to get around to (in fact, I’m told the Boris/Truss chaos delayed it).

But as things currently stand, because of the way Parliamentary timetables work, we’re looking at 2024 at the earliest, unless a General Election intervenes and delays things even further. So it’s up to us, nerds who read long Substack posts, to keep the pressure on and remind the naysayers that we can build a better society. And it starts with the scooter in my garage.

Phew! You made it to the end. So this must have been either a good read, or great hate-read. In any case, make sure that you subscribe (for free!) to get more blazing hot takes on a wide range of topics direct to your inbox.

Or if you really like my work, you can pre-pledge a subscription. This means that you want to support my work – and if I ever make the leap to going paid, I’ll be able to write more regularly and not need to worry about how to pay for food and shelter.

Oh, and you can still follow me on Twitter, which as of the time of writing is still – just about – a usable product.

And finally, please do share this post with your friends, followers and anyone who you think might find it interesting.

You can find it next to the boxes of ten thousand Rehman Chishti t-shirts I bought as a speculative investment. On an unrelated note, would anyone like to buy a significant quantity of rags?

Even if I wanted to break the law, it would be unwise to do so now that on an estate where literally 50% of the houses have video doorbells (I counted, because of course I did). So if I were to go for a scoot, I can guarantee that within minutes the local Facebook group would be lit up with video clips from curtain-twitching neighbours demanding action against the fat, balding, 35 year old scooter menace.

This footnote is to acknowledge the inevitable “the pandemic isn’t really over” response and to preemptively roll my eyes.

Obviously in some cases, it could conceivably be possible to build, say, new railway lines or even new roads to offload the transport burden to elsewhere. And this should obviously be done too. But don’t forget in this specific case this is Britain we’re talking about, and we don’t build things here.

I’m sure transport people could add a bunch of caveats to complicate this model but none of this is relevant for the point I’m making here.

This footnote is to acknowledge that yes, there will some circumstances when cars are necessary, such as when people with limited mobility need to get around, or trades-people carrying equipment, and so on. But you know what would make life easier for them too? Fewer cars on the road that don’t need to be there.

The same report estimates that in the study period, just five rental trials around the country removed between 1.2m and 1.6m kilometres of car travel from the road.

Though if it was practical and I was fit enough, I’d still pick a bike over a car any day of the week, given how a car is basically a time-bomb that a couple of times a year will force you at short notice to unavoidably spend several hundred pounds at a garage getting something fixed.

This line exists purely because I know there’s going to be a bunch of cyclists, probably wearing their lycra, fingerless gloves and helmet, sat in front their laptops, typing a furious response to this.

This isn’t an abstract example, this is from my personal, rage-induced lived experience, as the council in a neighbouring borough to me recently rejected building a segregated lane along one of the major roads heading to the town centre, because of local ‘concerns’ about parking. Needless to say, I am writing this wearing Joker make-up.

And just to expand on this more: Completely subjectively, I’ve definitely seen a lot of new build estates on the fringes of existing towns, presumably because it’s an easier sell than bulldozing existing low-density housing or redeveloping brownfield sites. The problem is that they always seem so disconnected, and living in them pretty much always requires a car.

If you’d like to contribute to my fund to one day afford an electric car, pre-pledge your subscription to this newsletter.

I’ve never smoked cannabis. I’ve never even smoked a cigarette. So it really pains me when there’s a scandal about Ministers taking drugs when they were younger, as it reminds me that I’m objectively more boring than Tory cabinet ministers.

I’m pretty agnostic on whether the e-scooter rental, as it currently works, is the best idea. Obviously there’s utility for all of the reasons described above, but I wonder if they’d actually work better if they were more tightly regulated. London, for example, only officially lets you park a scooter in given spots and apps use GPS to verify it – but perhaps it would make sense to have just one scooter fleet, and even to insist that scooters are physically docked like Boris Bikes are – the technology doesn’t need it, but it would create more of a sense of order on the streets. (Not to mention docks could act as chargers.)

This isn’t direct evidence of this, but I think one of the conclusions in the DfT commissioned report I mentioned points in this direction, as it suggests that “the patterns suggest that long-term users are more likely to travel more frequently, for longer and for commuting purposes. Private ownership may therefore encourage more regular use and more use for work-related purposes.”

My favourite recently discovered phrase is "multi-modal arseholes". Some people are idiots whether they are cycling, walking, driving or scooting.

And, if they are idiots, I would rather have them being idiots on a little scooter than in a tonne of car.

Just imagine the scooter parking. They’re so small, you could convert a single roadside car space into docks for at least 15 eScooters. It could become a completely normal expectation to be able to park within 20m of wherever you’re going.