How to use NHS data for scientific research – without creating a privacy nightmare

What happened when Ben Goldacre stopped writing fun popular science books and got a real job instead.

Former Chancellor Nigel Lawson famously said that “the NHS is the closest thing the English people have to a religion”1.

But I think he was only partially right.

He’s correct in the sense that the NHS is something many people turn to in times of crisis, when we or the people we love are at their weakest. Sometimes, like religious belief, it makes us feel better too.

And much like religious apostates, if you dare speak ill of the NHS, you might suffer negative social consequences.

But where this tortured religion metaphor breaks down is that unlike religion, where we can study the sacred texts to place ourselves on a path to enlightenment, the NHS often keeps its divine wisdom locked away.

That’s right – what I’m actually writing about this week is how the NHS shares its data.

It’s an important issue because the NHS is bigger than just a healthcare system. It’s also an incredible population-sized dataset.

Think about what’s hiding within our health records. Because we have so many people and such a heavily centralised health service, the information the NHS holds about us, in the hands of scientists, could be key to future medical breakthroughs, like the invention of new drugs, or the discovery of new treatments and better ways to care for people.

In fact, at risk of getting ‘spiritual’ about the national religion, I think we almost have a moral duty to open up our NHS data and put it in the hands of scientists – such is the opportunity to make the world a better place by studying it.

But this is easier said than done, because in many cases the health service is actively hostile to sharing information, and there are complicated reasons behind it.

For example, there's the institutional design of the NHS as a system. There isn’t really a singular ‘NHS’, it’s more a collection of independent services with their own objectives and incentives, so coordination is hard. And then there’s the more practical matter that IT systems in the health service are often wildly out of date, or maybe even not “IT” at all, and still paper based2.

Perhaps the biggest reason though is that often we don’t want the NHS to share our data.

I think this is understandable. My medical records contain my most sensitive and potentially embarrassing personal data, second only to my Deliveroo order history. I mean, I once had surgery to dislodge a kidney stone, and I absolutely do not want the world to know how they got the laser inside of me to zap it3.

This unease is probably why by 2021, over a million people had opted out of an NHS scheme that would have shared health record data for research – and is why the plans were subsequently scrapped.

But luckily, it turns out that this wasn’t the end of the NHS’s data sharing ambitions. In fact, in the years since the opt-out debacle, a much better alternative has emerged.

That’s why this week I’m excited to tell you all about a platform called OpenSafely, which does something amazing: It lets research scientists dig into 58m NHS health records – while seemingly doing the impossible and completely preserving patient privacy in the process.

It’s the brainchild of Ben Goldacre (yes, that Ben Goldacre, of Bad Science fame!) and his team at the Bennett Institute at the University of Oxford. They began work on it during the pandemic as a means to connect scientists with health data so that we could learn more about the virus and how to fight it.

And given that it was – and continues to be – a huge success, I’m surprised we don’t hear people constantly raving about it4.

So read on, and let’s learn more about how it works!

If you like nerdy politics, policy, tech, data, and media stories, then you’ll probably like my Substack. Why not subscribe (for free!) to get more of This Sort Of Thing directly in your inbox?

Insides Out

The fundamental problem with opening up health data is that once you hand it out, you lose control. So even if we trust the NHS to handle our records sensitively, and even if we trust their systems to remain secure5, we can’t be as confident once data falls into the hands of others. And unlike a password or credit card number that can be changed, once our health information is out there… it’s out there.

It’s easy to understand then why data getting loose is real worry. Not just because of the threat of serious hackers looking for personal information to sell on the dark web, but because it’s easy to imagine a spreadsheet containing sensitive information pinging around between academics as a normal part of their work, but ending up accidentally uploaded to the public web or emailed to the wrong person, and so on.

This is why the Bennett Institute has done something really clever: It’s turned the normal way of doing things on its head. Instead of our data being handed out, it has instead built a platform that lets scientists carry out research on health records without any personal data leaving the data-centre it is stored in.

In tech circles, this is known as a “Trusted Research Environment” (TRE) – a software gatekeeper that sits between the data and researchers, and carefully controls how data is accessed and what data is shared back with the scientists6.

The way it works is that if you’re a research scientist with a hypothesis, you write some code to interrogate the data and submit it to OpenSafely, which will then run the code on its own system inside the data-centre, and then it will send you the results back.

Crucially, it doesn’t send back specific patients’ information, but only the most high-level, aggregated information that you need to learn about the relationships between treatments and conditions, and so on7.

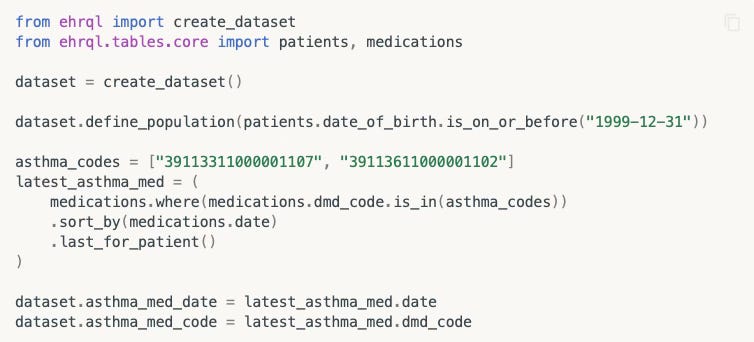

For example, to pinch from OpenSafely’s tutorial documents, imagine you wanted to study people who were born during this millennium, who had taken a specific type of an asthma medication. You can instruct the system to filter down the millions of medical records to just the cohort of people you want by writing a few lines of code in a modified form of the Python programming language.

Then you can add some more code to interrogate the data how you wish (eg, what happened if they also took some other medication at the same time?) – and instruct OpenSafely to spit out the high level results into a file, or display a graph.

And again, it will do all of this without you ever seeing a single individual patient’s records.

What makes this even smarter is that though the code might look relatively simple to anyone who knows a little Python, OpenSafely’s systems are abstracting away a huge amount of complexity under the hood to make these sorts of queries even easier for the end users.

For example, in reality health records are stored in two different formats, and legally the data is owned by individual GP practices – but because OpenSafely takes care of mashing up these different databases behind the scenes (and because the data never leaves NHS servers8), the scientists doing the research don’t need to worry about any of this9. They just get the results they need.

Privacy and transparency

OpenSafely isn’t the first organisation to create a Trusted Research Environment like this. It isn’t even the only TRE inside the NHS – but what I think really makes it remarkable is just how beyond-reproach it is in terms of privacy, to the extent that it seems like everyone is happy with it – and I do mean everyone.

What really sold this to me was when I saw a video of Ben Goldacre giving a talk about the platform. He mentioned a group called MedConfidential, who he affectionately described as the “most feral” privacy activists.

It’s an apt description. The group is led by Phil Booth, a veteran of the NO2ID campaign during the Blair years, and it is utterly vociferous in its commitment to protecting patient privacy.

In fact, over the years as a tech journalist, there’s been a few occasions when I’ve turned to Phil to get a feisty ‘sceptical’ quote to balance out whatever wide-eyed and naive privacy nightmare I’m writing about.

So when Ben explained that MedConfidential had endorsed OpenSafely, my jaw dropped.

More important though is that the reason for their endorsement is not just because Ben has been shaking the right hands, uttering the right platitudes about privacy, or writing rules that ask people behave when using the platform. What’s make OpenSafely bullet-proof is that it has privacy and transparency baked in by design.

For example, if you like you can go and check out a real time log of the jobs being performed by the OpenSafety system.

Even better, any code that runs on OpenSafely is required to be open source, meaning that anyone can go in and take a look at what scientists are trying to do with the NHS data. And this isn’t just a rule on paper – the system works by integrating with the development platform Github, which makes every line of code publicly visible, whether scientists like it or not10.

Add this all together then, and what you have is a system that can safely rifle through NHS health records without revealing any information linked to individuals, that is fully auditable – and open for anyone to look at. Amazing.

Getting Results

You can probably see why I’m excited by the existence of OpenSafely. As I might have mentioned before, I think that open data is broadly a very good thing11.

What’s more exciting though is that OpenSafely is already getting results. In the few short years of its existence it has already yielded a tonne of scientific papers based on NHS health record data, each incrementally improving our understanding of Covid and how to fight it.

That’s why it seems obvious to me that we (ie: Britain) should be taking the OpenSafely approach and using it to do so much more12.

And the good news is that it appears that the ambition is there to do this. In November last year, NHS England announced a new three year funding deal that will help the team scale up so they can help scientists research the likes of cancer, diabetes and asthma. Great!

But here’s what I find slightly weird. I understand this latest tranche of funding is only worth around £4m per year. In government spending terms, that’s basically nothing. And given the potentially transformative research that could be done, even when you take the other pressures on the public finances into account, shouldn’t we be spending a little more to scale it up faster?

In fact, I understand that the OpenSafely team has already designed a Trusted Research Environment that is similarly privacy preserving, but is specially optimised for AI – but because of the way government and the health bureaucracy works, as things stand there isn’t an obvious mechanism to acquire the funding to actually build it.

But this seems like a very solvable problem, especially as again, the money is basically chump change.

I mean, given the NHS budget for 2023/24 was £168.8bn, it means that the annual £4m of NHS funding for OpenSafely is equivalent to what the NHS spends in about twelve and a half minutes. Or just over ten lengths of Captain Tom’s garden.

Given the potential world changing benefits of such a system, should we not be working to expand it as much as possible to, well, safely open up Britain’s troves of health data? Could we not give them 15 or even 20 minutes worth of money?

And there’s also a massive opportunity for the government to apply the OpenSafely approach even more broadly too. Ben Goldacre has previously spoken about how the same sort of Trusted Research Environment could apply to other bits of government, like the Department of Education’s National Pupil Database. That’s conceptually very similar to NHS data, in that it’s a massive, information-rich dataset, but contains some obviously extremely sensitive information.

I guess ultimately then, I think my argument is basically “more of this please”, and no one sums up the opportunity better than Ben Goldacre himself, who in 2022 wrote:

“Seventy-three years of complete NHS patient records contain all the noise from millions of lifetimes. Perfect, subtle signals can be coaxed from this data, and those signals go far beyond mere academic curiosity. They represent deeply buried treasure that can help prevent suffering and death around the planet on a biblical scale. It is our collective duty to make this work.”

Preach!

So perhaps it is time for the government to make a leap of faith – and scale up OpenSafely so we can make the most of the national religion.

If you like nerdy politics, policy, tech, data, and media stories, then you’ll probably like my Substack. Why not subscribe (for free!) to get more of This Sort Of Thing directly in your inbox?

And if you enjoyed reading this, please share this post with your friends and followers, as that’s the best way to help my Substack grow!

This quote has become such a hacky thing to reference that it’s actually quite difficult to find the original form of words – googling the phrase and words around it merely have other people quoting it. And some other sources say “have now” not just “have”.

I’m not joking – as of last year, “hundreds” of hospitals were still reportedly using fax machines.

Let’s just say this is one part of life where women have it easier than men.

By “people” here I mean politicians, scientists, academics, bloggers – the sort of spods who read my Substack basically. I admit that as clever as the system is, it might be a hard sell to get “data-driven scientific analysis” on the next series of Gladiators.

Perhaps not the safest of bets.

I’ve been trying to think of a metaphor for this, and the least glamorous I can come up with is that it’s like buying something from a petrol station in the middle of the night, when you have to stand outside at the little window, and have the attendant go and grab you a bag of crisps instead of picking it off the shelf yourself.

It reminds me of how TfL uses data from mobile phones to track how we travel – but only gets it in aggregated form from O2, which acts as the gatekeeper.

I’m collapsing quite a lot of complexity here that will have health professionals getting mad. GPs remain the data controller for your health records, but because this is the modern world, that doesn’t mean they sit on a computer in your GP’s office. Instead, your records are almost certainly stored on systems made by one of three major software vendors who make records management systems – who in turn probably ultimately just store your records on cloud servers owned by Amazon or Microsoft. But my point is that legally your records are staying within the NHS, and are not being passed about willy-nilly.

There’s also a very clever thing it does where it will generate realistic-ish dummy data for you to use during the coding phase – so that once you run it on OpenSafely’s TRE to get the real data, you can be confident that you’re going to get what you’re expecting.

This also has the added benefit of stopping “P-hacking”, the bad scientific practice of manipulating data to appear significant, even when it is actually meaningless, because anyone can check how a piece of research was done.

In fact, after I started researching this piece I later learned that Anna Powell-Smith, my PAF-campaigning colleague, actually worked at the Bennett Institute and helped get it up and running in the first place.

To be clear, the OpenSafely approach won’t work for everything in the health service. That’s why the NHS is currently building the conspiracy-theory-laden Federated Data Platform with Palantir – which will be used by hospitals that are actually delivering care to people. Because if you want to tell doctors what to do with specific patients, you can’t really keep that data private like you can from research scientists who don’t care about individuals.

Also, this is Ben Goldacre's second big data project in the NHS (that I know of): the first was OpenPrescribing (https://openprescribing.net/), which gave an overview down to GP level of what was being prescribed where.

James, spare a thought for poor Samuel Pepys who, without anaesthesia, had a bladder stone the “size of a tennis ball” removed using a scoop inserted into a cut in his perineum (which was never stitched up). The only good news about this tale is that tennis balls were a bit smaller back then.