It would be mad for Labour to dump the £28bn climate plan

"Growth must become Labour's obsession."

I am, for better or worse, quite a paranoid person.

If I leave the house for anything longer than a trip to the supermarket, then chances are that I’ll carry a high-capacity USB power pack to charge my phone. After all, you never know when your car might break down or if you’ll be caught in a natural disaster and need to live-tweet it.

When my partner and I go on holiday, I’m even worse. After I’ve rattled the front door a few hundred times to check it is properly locked, I’m not happy unless we’re at the airport at least three hours early1. In my carry-on bag, I’ll have several spare USB cables and plug adapters, for added redundancy.

And once we’re wandering around the cathedral in the historic centre of whichever city we’ve landed in, I’m always tapping my pockets and grasping my bag behind me to check my spare USB cables are still inside2.

Whether this is healthy vigilance, or symptomatic of an anxiety disorder is beside the point. But what I do know is that despite all of these weird things that I do, I’m significantly less paranoid than the Labour Party.

That’s because as much as they might hate to admit it, they’re currently doing great.

Since Autumn 2022 the party has maintained a double-digit polling lead. Translated to seats, Labour can probably expect a majority of 100 or more, while there is a non-zero chance that the Conservatives could face a “Canada ‘93”-style total-wipeout.

In other words, Labour are on track for a majority that can be accurately described as “stonking”. Not that you’d know this from the way that their people are behaving.

For months now, there has been speculation that the party is planning to cull its £28bn “Green Prosperity Plan” because of concerns about how it will go down at the ballot box. And anyone who is paying attention can’t have missed the constant drum-beat of stories urging them to drop the guillotine.

For example, last October the FT reported that Labour was considering further reducing the plan’s headline figure by £8bn, having already walked it back to £28bn by the end of the Parliament, instead of spending that much every year from the get-go.

Similarly, back in November, there were reports that Labour planned a scale back based on the need to adhere to the party’s proposed fiscal rules. When asked about it in interviews, this is how Labour politicians have tended to give themselves the rhetorical wiggle-room to later backtrack, even when ostensibly defending the plan.

The slew of stories has continued into this year too.

A couple of weeks ago, it was reported that the party chose not to include the £28bn figure in an election strategy document. And then last week it was reported that Labour was reportedly planning “crunch talks” to decide the future of the policy.

Similarly, influential Labour-aligned figures have shat on the policy too. For example, John Rentoul has long been a sceptic. And at the end of last week, former Shadow Chancellor and famous Twitter meme Ed Balls waded in and suggested the party should perform a “big U-turn” on the policy.

So there are clearly plenty of people in the party gunning for the policy. And there is a valid political argument to do so. I don’t think the opposition is because people think £28bn would be bad in policy terms, per-se – but rather the concern is motivated by an understandable state of paranoia: The party is on the verge of power and the fear is that this policy might fuck it up, because the Tories could weaponise it against them.

However, I think that this analysis is wrong. That’s why when I saw Ed Balls’ intervention, I thought of two very different words that I’d like to tweet at him.

So this week, I’m going to explain why I, some bloke on the internet, knows better than the politicians and professional political operators. I think that paranoia about the policy is a misread of current political circumstances – and I think that Labour would be mad to drop the plan.

Read on to find out why.

Subscribe now for free to get more blazing hot politics and policy takes direct to your inbox.

Fighting the last war

It’s easy to imagine why the policy might spook Labour people.

A major part of the Starmer project has been to rebuild Labour’s economic credibility. That’s why Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves has committed the party to stick to Tory tax and spending plans, following the template set in 1997 to reassure the electorate that Labour aren’t too scary. But there is one big exception to this rule: The £28bn of climate cash.

This makes it a potent dividing line. During the next election campaign, it’s inevitable that the Tories will attack this figure relentlessly, trying to frame Labour as economically reckless.

Imagine if they were able to deploy an anti-£28bn slogan with the same iron discipline as they did with “Long Term Economic Plan” in 20153, or “Get Brexit Done” in 2019. Through sheer force of will, it would surely make the climate plan one of the more salient policy issues during the campaign.

However, I’m not convinced that the same trick will work next time around because the circumstances will be very different.

The reason those two slogans were so brutal was because they punched real Labour bruises: In 2015, the party was (fairly or unfairly) viewed as having played a role in the 2008 financial crisis, having been in office at the time when it happened. And in 2019, it is genuinely true that Labour did not have a settled position on Brexit, because the party was divided internally over both the substance of the issue and how to approach it.

But next time around? Even if the Tories come up with the most devastatingly effective slogan in political history4, it will be blunted by the real world circumstances of the Tories having spent the last several years burning every last ounce of their own credibility5.

On a surface level, this means that if the Tories attack the policy as irresponsible, it can be neutralised with just two magic words: “Liz” and “Truss”6.

But the problem for the Tories goes deeper too, as there is no form of words that is going to trump voters’ lived experience of not being able to get a doctors’ appointment, and a weekly shop costing £150.

In other words, though the Tories might be great campaigners, they’re not going to solve the structural problems of a broken public sector and inflation pushing up prices with some clever messaging. And because of this reality, Labour can go into the campaign not unencumbered by messaging concerns, but with much greater room for manoeuvre and a much more sympathetic electorate than when facing a more popular opponent.

The Uxbridge fallacy

There is, however, an even better reason to not drop the £28bn policy. Because to do so would be misreading where public opinion actually is on the substance of the policy.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to make a “but the policies were popular!” argument like the ones heard from Labour’s Corbynite wing, trying to explain away the disaster of 2019.

I acknowledge that in an election, you need to be able to sell a package of the leader, the party’s mission, and the retail policies – which makes evaluating policies in isolation not that meaningful an exercise.

However this said, it is also true that other than the Tory weaknesses described above, another structural fact of the next election is that voters really do care about climate and the environment.

It’s often under-appreciated, but for several years now it has been the case that the environmentalists have won the argument – and today climate routinely polls as one of the top issues for voters7.

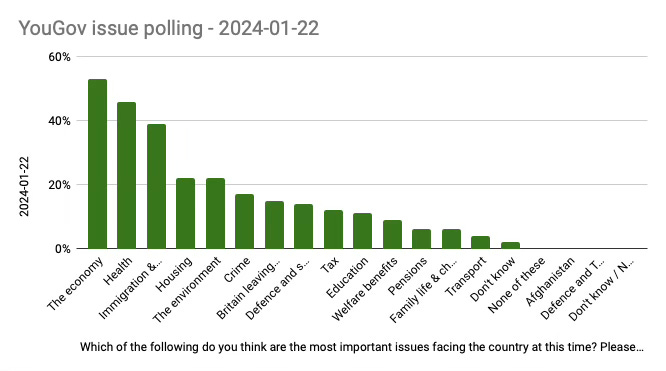

For example, according to YouGov’s most recent issue tracker, today “the environment” is ranked as the joint-fourth most important priority by voters (respondents are asked to pick up to three issues). That ties with housing – another signature Starmer issue. And lags behind only the old classics of “The economy”, health, and immigration. People care about the environment more than tax and schools!

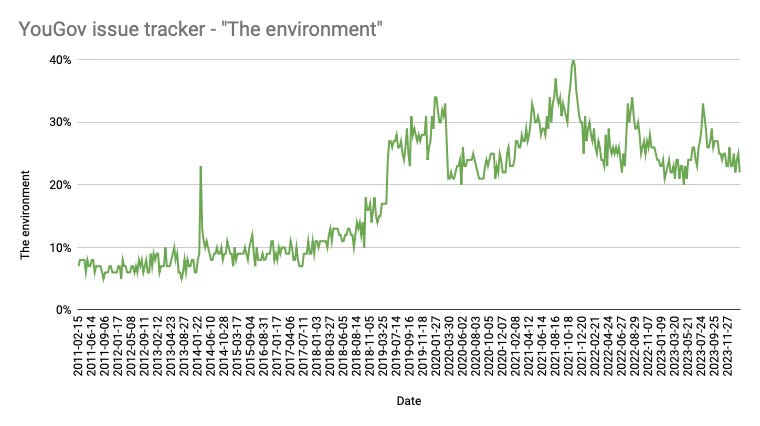

In fact, viewing the change over time is similarly striking. Here’s the percentage score for “the environment” in every YouGov tracker poll since 2011 – what’s clear is that there has been a step change in the salience of the issue, starting around 2019. That’s why Boris played up his support of Net Zero. This is no longer just some weird important-but-niche concern, like, say, liberating the Postcode Address File.

Relatedly, as I’ve said before I think the idea that voters do not support climate measures is simply incorrect – and that the anti-Net-Zero reaction after the Uxbridge by-election was an enormous over-correction not reflective of what the result actually meant.

What’s obviously the case is that voters do not like measures that directly make their lives worse. That’s why the ULEZ was so unpopular – that’s a monthly bill people see on their bank statements, and it is being imposed to almost be unpopular with motorists by definition, as the goal is to reduce car usage.

That’s a very different proposition from a Green Prosperity Plan promising a supply-side intervention that will make energy bills cheaper and move Britain closer to energy independence. And I think the public are smart enough to realise this.

In fact, you don’t need to take my word for it. I strongly recommend reading this piece from Steve Akehurst, in which he carefully parses the polling around the £28bn figure.

To my amazement, he concludes that framed in the right way, with a message around either economic growth or energy independence, the climate spending can conceivably make Labour actually slightly more popular.

Doing the right thing?

This brings me to my final argument on why to stick with the £28bn plan. And that’s the, er, actual policy substance. Which is actually quite important.

Don’t worry, I’m not going to start earnestly explaining that the policy is a good idea because I believe it is The Right Thing To Do™️. As Matt Yglesias has noted, doing The Right Thing is often overrated in politics8. As important as the climate is, correctly from Labour’s perspective, it is more important that Labour form the next government than remain ideologically pure.

The reason to keep the climate commitment then isn’t for sentimental reasons – but because even if you don’t give a shit about climate change, the Green Prosperity Plan is integral to Labour’s broader ambitions.

For example, the plan really would help Britain move closer towards energy independence. This would be a major strategic victory, as we would seriously mitigate the risks of international energy supply shocks, and Putin and OPEC’s ability to dick about.

The plan would also reduce energy bills – reducing a burden that disproportionately affects the poorest in society. And the investment in green infrastructure would create thousands of skilled “blue collar” jobs, as we’ll need a workforce to deliver the infrastructure – so the policy delivers to the demographics who are Labour’s historic core supporters9.

But most importantly the Green Prosperity Plan is designed to be the engine that causes the much needed economic-growth that underpins any ability to spend more money on, say, public services like the NHS.

That’s why “Growth must become Labour's obsession,” said Keir Starmer back in December. And if the investment isn’t made, achieving any growth is going to be much more difficult.

And that’s why the idea of ditching the policy seems pretty mad to me – because it isn’t just a limb that can be cleanly amputated. It is at the core of the Starmer project – and it is a critical part of making the rest of the party’s plans for government work.

The slightly-too-paranoid style

It seems like a good rule in political campaigning is to take nothing for granted. After all, no votes have actually yet been cast. If you’re the party leadership, you want to keep your troops under the impression that all could be easily lost, as to think otherwise could invite arrogance and complacency.

But the reality is that Labour’s polling position really is incredibly good right now. And that’s why I find the chatter about dropping the £28bn pledge so bizarre.

As things stand, according to the recent Telegraph/YouGov MRP poll, Labour looks set for a majority of 120. That’s a gain of 183 seats – and a bigger majority than Boris won in 2019 when faced with a uniquely weak opponent.

Simply put then, that’s a predicted majority so large that I’m left wondering… who is left to win over?

And this is why – as fate-tempting as it may seem – it’s important for Labour to acknowledge the extremely good reality of its current situation. Because the overwhelmingly likely outcome makes the trade-offs around the Green Prosperity Plan very different than the trade-offs imagined when taking a distorted, more paranoid view.

If Labour were desperately behind, then it would make perfect sense to compromise on the policy, and maintain a strategy of ultra-caution. Not doing this is why the self-indulgent Corbyn years were such a disaster. They didn’t anchor policies and messaging to where the voting public actually was, and paid the price electorally.

But now Labour is 20 points ahead, and is putting up a credible fight in the bluest-of-blue constituencies10, so the trade-off is instead about caution versus winning a mandate to actually deliver a policy agenda.

And sure, Labour could max-out the caution strategy entirely and maybe claim a few more seats – but (and here’s the most controversial part of this piece) I can’t help but wonder if it’d be better trading, say, a majority of 120 with a mandate for making only relatively minor changes, for a majority of 100 – plus a mandate from the electorate for rolling out the Green Prosperity Plan and the other more ambitious parts of its agenda?11

Paranoia, as healthy as it might feel, can only get you so far. There is such a thing as being too cautious. And I can tell you from the weird glances that my partner gives me, you can only tap your pockets to anxiously check your phone and wallet are still there for so long, before you start to look demented.

Phew! You made it to the end! So why not subscribe (for free!) to get more politics and policy takes direct to your inbox?

And don’t forget to follow me on Twitter – and Bluesky just in case.

When I went to Egypt a few years ago I turned up at Heathrow five hours early, because I was so worried about the Piccadilly Line going down.

Helpfully I also have a bag that zips on the inside against my back, as an extra layer of protection against pick-pockets.

Given Brexit, Covid and Ukraine it’s funny how this turned out in retrospect.

“Free the Postcode Address File”.

There’s also the very real political reality that given the current state of the Conservative Party, even if they pull together a bit for the election, it seems vanishingly unlikely to me that the party’s MPs and foot-soldiers will be able to exercise the sort of discipline required – not least when half the party will be only using the election campaign to gear up in anticipation of the imminent post-election Tory civil war.

Incidentally, those are the same two magic words that will blunt any attacks that try to associate the Starmer regime with that of Jeremy Corbyn.

And sure, there are significant differences between “climate” and “conservationism”, but this is a pretty decent proxy!

Though, full disclosure, it was when this policy was first floated that I first started taking Keir Starmer seriously and became a bit of the Starmer shill I am now.

Maybe they should commission a poem for every new wind turbine to give their other core supporters, English graduates in poorly paid academic jobs, a piece of the investment windfall too.

I think a really striking example of this is the Harborough constituency in Leicestershire, where ex-Cameroon-policy-wonk-turned-unconvincing-culture-warrior Neil O’Brien has quit his role in the government to focus on fighting to retain the seat, which has been comfortably blue since 1924, save for 1945 when Labour scraped in by a few hundred votes.

You can tell me why I’m wrong about this in the comments.

Something that I think more political-types should remember about government spending is that most people think that vast amounts of current spending are wasted and that, by switching money from wasteful things to the things that they want done, there would be no need to increase taxes to spend money on actually important things.

Not only that, they are right as individuals, though they are wrong as aggregates. There are a host of major government spending commitments that 5-10% of the country thinks are complete wastes of money and could be cancelled entirely. The military (for pacifists). The NHS (for libertarians). The police (for lefties). The entire legal system (for righties). Transport (for NIMBYs). "welfare" (for evil people). And so on. Every major spending programme has majority support in the UK. But a majority of people oppose at least one of the things that the UK spends £28bn or more on already.

But most people think they, themselves, are normal, and that most people agree with them. People really don't like being told they are in a 5% minority. I don't get why; I'm in minorities that small or smaller on all sorts of things and I'm fine with that. But most people don't. So they fool themselves that far more people agree with them than actually do and then wonder why (insert object of ire) is still going after all these decades. If you're attentive to politics and to wider popular opinion, you know the answer (plenty of Tories would happily scrap the NHS, but they have to say otherwise. Corbynites wanted to scrap the MOD, but even in opposition, they pretended otherwise and they never would actually do it in office). But, as we all know, most people aren't attentive to politics and popular opinion.

Most people also think there is a lot more fraud and abuse than there is - the COVID-era PPE scandal was a scandal precisely because that amount of fraud is really unusual, but I think the general perception is that it is the normal state of affairs, and they're just pleased someone finally got caught.

What this means is that the link between increasing spending and increasing tax in the popular perception is much weaker than you'd think, which is why not spelling out tax increases doesn't result in people thinking "oh, they're going to put up taxes", but in "they're finally going to eliminate the terrible thing that I have always opposed" or "they're finally going to stop the fraud". And that's why "Labour's Tax Bombshell" can work: people don't think spending programmes come from tax increases, but when a credible messenger tells them that they will, they dislike that. The point here is, as you made (correctly) clear: the Tories aren't credible messengers. If they say "Labour will put your taxes up", much of the public will tune out or say "pull the other one".

Really liked this. Two thoughts:

(1) You are totally right to bring up Liz Truss, who is a serious blind-spot for most politically engaged commentators, pundits, and strategists. As far as most of these people are concerned, Truss has been memory-holed, and the news cycle moved on from her long ago. But I think this understates how much The Truss-aster cut through with those who don't usually follow politics that closely. I guess you can't write a column every week about how Truss effectively doomed the Conservatives, even if it remains true.

(2) As I understand it, one of Labour's big worries is that making big spending commitments plays into the perception that Labour is the party of higher taxes. I think this gets the logic the wrong way around, for two reasons. One is that this perception is so baked-in that nothing Labour says will convince voters otherwise. The other is that even if there was no £28bn plan, Labour would have to raise taxes because the fiscal status quo is unsustainable. Labour should just be upfront and say it will do this, even if it means raising taxes, because that's what voters think anyways and at least the party will look more honest than it does now. In any case, falling interest rates will mean mortgage costs will go down for the kind of voter Labour really needs to reach, and that feel-good effect will cancel out any tax hikes.