The birth rate weirdos have a point (about this one specific thing)

RETVRN (to boring, technocratic social democracy)

Last chance to get in on the ground floor! I’m still totally blown away by how many people have pre-pledged a subscription to tell me that you’d like me to write more regularly. The numbers are now tantalisingly close to it making business sense for me to post every week. So if you haven’t already, please do tell me you value my work by pre-pledging! Because this could be your final chance to get in on the ground-floor, before I launch a premium subscription tier.

Tell me fun politics and policy gossip: I know I’ve got a bunch of well-connected readers who work in interesting places. So I want to remind you that my emails are open for you tell me about cool stuff. I’m not really a scandal-breaking mischief-maker, but if someone in Whitehall is planning on digging any interesting railway tunnels or, say, liberating any Postcode Address Files, I’d love to know and write about it! My email is psythor(at)gmail.com.

There are few big choices in life where you can be utterly confident you have made the right ones.

Did I choose the right career? Did we buy the right house? Was it really a good idea to sell off a critical public dataset?

It’s impossible to know for sure.

But there are other choices that are more difficult to question.

For example, every time I’m on a train or a plane and I hear a child start to scream and cry, I simply pull my noise-cancelling headphones over my ears, close my eyes and smugly think to myself “that’s somebody else’s problem”.

This is because my partner and I decided independently, long before we ever met, that we don’t want to have kids. Because it turns out that having free time, disposable income, and cool holidays is brilliant. Even if some people do bring their annoying kids on to the plane with them.

However, I recognise that not everyone thinks like we do. Perhaps raising a child is fulfilling, life-affirming and gives life definition and purpose? I’ve got no idea, I’m too busy gaming on my Playstation 5 and living a life of selfish consumption.

But what I do know is that there are increasing numbers of people who are more like my partner and I. Because new ONS figures published last week revealed that the birth rate has fallen to its lowest point in 20 years, with just 605,479 live births last year – down 3.1% on 2021.

The ONS hasn’t yet calculated the fertility rate – the average number of children per woman – because the 2022 population data hasn’t yet been tabulated. But the 2021 figure was 1.61 – compared to 1.58 in 2020. So we can safely assume that unless something incredibly dramatic has happened, we’re still a long way below the optimal ‘replacement rate’ of 2.08 kids per woman that you need to maintain a stable ‘natural’ population.

Obviously on one level, this is great news. It means that getting on an Easyjet might be slightly more bearable and maybe more of my friends will still be available to go to the pub1.

But there are people who worry about this. For example, speaking at the ‘National Conservatism’ conference back in May, Tory MP Miriam Cates argued that the falling birth rate was the “most pressing issue” that Britain faces. And it is, of course, a problem that has been highlighted by the right-wing political science professor who political science professors love to hate, Matthew Goodwin.

And now here’s the worst thing. While I wouldn’t say it is the “most pressing issue”2, having thought about this during my many hours of child-free leisure time, I do actually think the birth rate worriers have a point and it is something that we on the left half of the political spectrum should care about too.

Uh-oh, where’s this going? This could be the most ominous opening since the time I argued the BBC is doomed. So make sure you subscribe (for free) to get more of This Sort Of Thing direct in your inbox. Or even better, pre-pledge a subscription to tell me that you value my work and want to support me writing every week.

Pyramid Problems

As I’m a godless liberal, my gut reaction on hearing people on the grottier end of the right talk about birth rates is – perhaps unfairly – to be immediately suspicious.

Is it actually the birth rate that the anonymous accounts with the Union Jack avatars are worried about, or is the issue more of a wedge to get women back into the kitchen and kick out the scary foreigners? Is it a weird religious thing? And is it really birth rates you want to talk about, or are you just looking for a reason to start measuring skulls?

I think this is because birth rate worrying is the right-wing equivalent of the electoral reform people on the left. You know there’s a germ of a point there, but anyone who makes it their main thing is almost always a bit of an oddball.

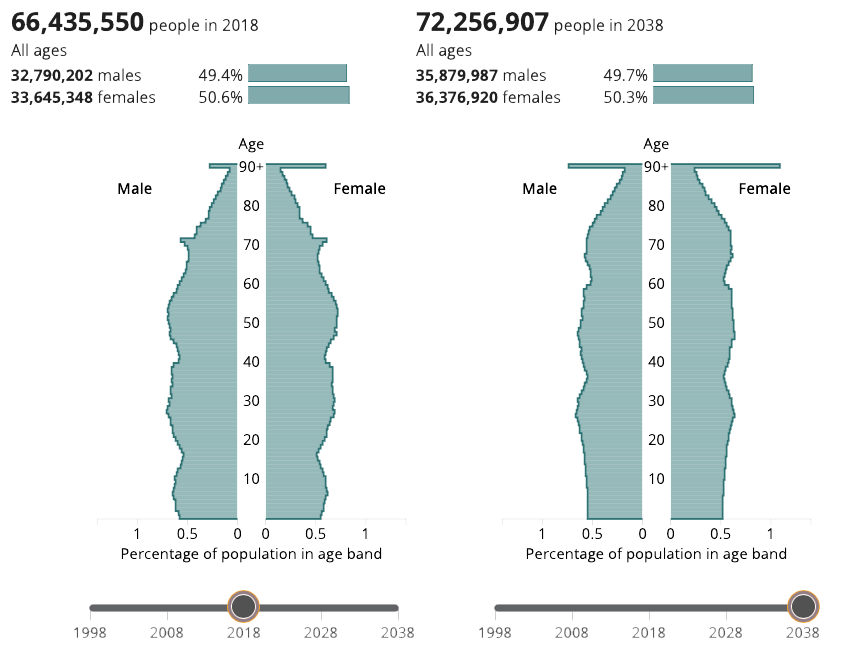

But taken at face value, there is something real at the heart of the concerns. And that is that the UK, along with the rest of the rich world, is getting older, and in few decades time that could really screw things up, because it will mean there will be many fewer people of working age supporting (and crucially, paying taxes) to support a much larger cohort of elderly people.

If this happens, this will be a bad a thing because of the hit on the public finances. If current trends continue, in 2038, Prime Minister Tom Harwood will be arguing with Leader of the Opposition Aaron Bastani during Prime Minister’s Metaverse Questions that there simply isn’t the money to pay for state pensions and the NHS.

So where I think the birth rate weirdos have a point is that this is something we should probably actually worry about. If we’re going to have a functioning welfare state in the future, then we should take this long term trend seriously – in the same way that we should take climate change or the rise of China seriously as major strategic policy issues.

And to be clear, as far as I can tell there is some dissent from this “demographic time bomb” model of the future. Here’s a BMJ article from 2013 arguing that an ageing population won’t be a problem, and in 2019 the ONS itself published a study arguing that it might not be a problem.

The gist of the argument is that though we will have an older population on average, people will also be a lot healthier, like how a 70 year old in 2017 was about as healthy as a 65 year old was in 1997. So it is conceivable that perhaps old people won’t be such a burden on the state as they are today… at least until they get even older.

But in my view, as a non-expert who bloviates on the internet, is that while these studies are an interesting contribution on the nuances of what the future could look like… It strikes me as a little breezily complacent to therefore assume that the ageing won’t be a problem.

So just as climate models could conceivably be off a bit, or like how China could suddenly lapse into civil war in 2035 and destroy its economy, the ageing population still seems to me like a major risk factor we should prepare for. And given that creating new working age adults takes absolutely ages, we should probably worry about it now.

Doomed approaches

If we accept that the birth rate is a problem, the question is: What should we do about it?

The most obvious solution is more immigration. This is instinctively appealing to me. I’m a hardcore Remainer and would unironically advocate for us to join Schengen. And ideologically, I’m as close to an “open borders” guy as you can get while still attempting to maintain the aesthetic of “serious, chin-stroking policy guy who isn’t completely mad”.

But as Stephen Bush pointed out in the FT last week, immigration may not be the magic bullet. Because even if we take in people from countries with high fertility rates, it seems pretty likely that within a generation or two, their kids will be just as liberal, wealthy and childless as everyone else.

And the broader problem is that the fertility rate is closely linked to wealth. Basically once a country gets sufficiently wealthy, it drops rather dramatically. So our prosperity is the mechanism that causes the problem. And assuming the rest of the world continues to get richer, as we should want to happen, the pool of countries from which to draw additional people will diminish too3.

So we really may need to encourage people to have more kids themselves. And this basically means there are two approaches we can try: What I’ll call the ‘National Conservative’ approach, or the ‘Scandinavian’ approach.

Both approaches have some shared characteristics (I’ll get to them), but what makes the NatCon approach unique is what makes birth rate chat feel so inherently icky. It’s the handwringing about the march of social progress, and an implicit desire to go back to some sort of imagined 1950s lifestyle.

In her speech mentioned above, Miriam Cates complained about the legalisation of no-fault divorce, how women want to go back into the workplace after giving birth, and how the last Labour government increased the number of kids who go to university (as well as a bunch of playing-to-the-crowd pablum about ‘cultural Marxism’4).

There is some good news though. Even if we imagine a bizarro-universe where the NatCon policy prescription was desirable, I think there’s basically zero chance of such a rollback on social policy ever happening for the same reason the socialist revolution is never going to happen.

Short of King Charles inviting the Taliban to form the next government, I’m struggling to imagine a political path backwards, to a world where women have fewer rights and less agency. Because that’s the bit where NatCon types tend to start mumbling: If you actually want a “natalist” social policy, then behind all of the happy talk about supporting families, you need to re-impose more restrictive abortion laws, and force more women to stay in abusive marriages, and so on. That’s the trade-off that needs to be made if the incentives towards having kids are to be rebalanced5.

And the bad news for Cambridge educated, former finance director and entrepreneur, and current professional politician Miriam Cates is that the gains made by the feminist movement over the last 50 years are surely far too entrenched to be rolled back now. The cage of norms that kept women back at home raising children has been thoroughly smashed at this point6.

And at risk of mansplaining, I think this is actually a good thing.

What will actually work?

There is however, another way. The way of boring old social democracy, as practiced in Scandinavia, that focuses on economics.

The argument is pretty easy to grasp, and doesn’t rely on magical thinking: If we have a generous and robust welfare state, where people feel a greater sense of financial security, maybe they’ll be in a better position to have children.

And to be fair, this is something that Cates acknowledged in her speech. In fact, it’s the reason I found myself agreeing with more of it than I expected.

“If a home and a job are basic foundations for starting a family, at least one half of that equation is hard to come by,” she told the conference, specifically calling out the sky-high cost of housing as a major problem. I couldn’t agree with her more.

It’s at least possible to imagine a world where, for example, we build more homes, so the cost of housing falls. Or a world where new parents receive more generous hand-outs, making the cost of having kids more bearable7. This is what they do in, say, Sweden, where parents get 18 months of parental leave, subsidised care and hefty legal protections.

This all seems pretty obvious to me. If you want to encourage people do something, then it’s important to shift their underlying material conditions, as that will shape their decisions8. That’s why it seems weird to me that Miriam Cates voted against expanding free childcare9.

There’s just one problem though.

As far as I can tell, from my non-expert perspective, there isn’t enormous strong evidence that the Scandinavian approach actually works either. For example, on headline figures alone, Sweden’s fertility rate is still only 1.66 – higher than the UK, but still below the stable replacement rate. Cates makes the same observation, pointing out that in Finland, one of the most generous countries, the fertility rate is even worse than the UK.

Similarly, here’s a long report from the Institute for Family Studies, an American think-tank that’s funded by, well, exactly the sorts of people you would imagine fund the Institute for Family Studies, arguing the same. It, like Cates, argues that there is a social/cultural component to fertility too.

And I think this is true to a point. It’s not a coincidence that the biggest step-changes in the fertility rate, other than the World Wars, was the the Abortion Act coming into force in 1968 (see the chart at the top). And hey, look at me and my partner. Even extremely generous government support isn’t going to persuade me to sacrifice any of my 12 hours a day of Twitter time to raise a child.

But even if the evidence for the Scandinavian approach is weak, or if it doesn’t deliver the fertility rate uplift that proponents were hoping for then, well, tough – because there’s no other choice.

It’s weirdly similar to the arguments over climate change: Even if the threat of climate change is really bad, there’s no way we’re going to stop using cars or flying on planes, and people aren’t going to vote to make themselves worse off. So any intervention to actually deal with it need to take this into account10.

So on the birth rate, the reality is that simply isn’t a viable path to going back to how things used to be. The ‘short-term’ gains from women having more rights at the expense of the birth rate are too convenient, useful and good on the merits to un-invent. So if we decide that the birth rate is something that we need to care about, then the only option is to invent policies that work in this real world, instead of the imagined one in our heads.

And if I figure out for sure what those policies are, I’ll let you know.

But in the mean time, at least if we try the social democratic approach, in the very worst case scenario where we don’t nudge the birth rate at all, at least we’ll have the consolation prize of having created a more generous and supportive welfare state that better cares for the families that do exist instead.

Minor correction: An earlier version of this post criticised Cates for voting for the welfare cap, as a humorous contrast with her stated views on how we need people to have more kids. A correspondent has kindly pointed out that the Very Funny Comparison doesn’t quite work, because while the Benefit Cap was bad and punished parents for having more than two kids (and was voted on before Cates entered Parliament), the Welfare Cap is a more technical measure that is about how the government sets spending targets. “It’s a bit of a nothing,” I’m told. Which is annoyingly less funny.

Phew! I didn’t end with a twist where I argue, contrary to the expert consensus, that the science of phrenology is sound. I’m not sure I’m big-headed enough to wade in on that. But if you enjoyed reading this, you might enjoy reading me attempting to upset both sides with my take on The Woke Stuff. Now don’t forget to subscribe (for free), or even better, be a hero and pre-pledge your subscription to get more of This Sort Of Thing every week.

And don’t forget to follow me on Twitter, Blue Sky, Threads and all that.

And in this era of algorithmic chaos, please do share this post with anyone you think might be interested.

Though one consequence of being childless, metropolitan liberals is that a massively disproportionate number of our friends don’t have kids either.

We all know that the most pressing issue the PAF.

I guess one extremely long term conclusion to draw from all of this is that every country ideally wants to have a ever slightly increasing population to maintain a tax base that can maintain services for the retired. I say this as someone who is extremely pro-density, but presumably there is a hard limit to this, but I guess everyone is assuming that by the year 3000 we’ll have enough robots to take care of the elderly or something.

The funny thing is I’ve previously explained why I’m a bit sceptical of the new ‘woke’ norms, but unlike the NatCons of this world, I at least have the decency to feel a bit embarrassed when I hear the phrase ‘cultural Marxism’.

My partner, who is a modern, empowered woman with a History PhD points out that, of course, even when divorce laws were more restrictive it didn’t actually stop people from splitting up. When the divorce laws were reformed in the 1930s, the reformist MP AP Herbert quoted the Archdeacon of Coventry, who said that “As the law stands at present those who wish to bring an end to the marriage were forced to take one of two alternatives—either one must commit adultery or one must commit perjury”.

It really is worth trying to imagine what a roll back of the last 50 years would actually look like in practice given a third of MPs are female, and we have powerful female CEOs and other public figures. And more generally, we have a large class of female professionals, etc etc. A world in which we reverse course on these social policies is just as unlikely as one where we nationalise the entire economy. Feminism has won!

Our household income is well above the median (£32k), but even if we wanted kids I can’t imagine feeling like I could actually afford such a thing – even though at least half of households are in an objectively worse financial position than we are. And this still holds true even if we were to do the unthinkable and cancelled our advert-skipping YouTube Premium subscription, which you’ll have to prise out of my cold, dead hands.

My own completely un-evidenced policy proposal is that it would make more sense to work on encouraging existing parents to have more kids, as presumably it is easier to persuade parents with 2 to move to 3, than have people go from zero to one, because the massive life-changing lifestyle change will be less dramatic. This also makes sense from a comparative advantage perspective too, where you get more economic gains from people specialising. So existing parents can specialise on raising kids, and we childless adults can specialise in going on multiple foreign holidays per year and writing long Substack posts.

Her actual reasoning on this, according to the article, is that she thought the policy was “separating parents from babies”.

I am 100% confident that a climate change metaphor is exactly what the 'NatCons’ reading will find persuasive.

The reason that many of my friends and colleagues with children have stopped at two is purely financial. The cost of a month's childcare commitments for parents who work full-time, or close to it, is equivalent to a month's rent or mortgage until the child is three years old. That's two years of paying two lots of that amount for an eldest child.

If you can manage to time a second so that you at least have one in 30 free hours and the other at full rate then you only have to worry about paying a mortgage and a third each month. I'd wager that one of the worst things that could happen to any couple planning for a third child would be their mortgage payments going up by £500 a month just as their nursery payments come down by the same amount.

Anyone that does have three children, spread out so they aren't doubling up on full whack nursery fees would be paying them for nine years.

Of course, for some people older realtives are available to help but that can mean one or two days a week rather than full time and it should be also considered that many of the couples who aren't having a third child are ones who don't live in the same part of the UK (or indeed aren't from the UK) as they were born in as they moved for university, moved for the graduate careers and their partner did they same so parents aren't 15 mins down the road like their grandparents are likely to have been.

Purely speculation but it could be that without the policies in place in Scandinavian countries their birthrates might be even lower!

As someone with 3 kids I completely agree with your point James about "encouraging existing parents to have more kids." If the government is serious about the issue.

This will be by far the path of least resistance.

We're not having any more due mainly to starting relatively late in life. But I could imagine a scenario where we had another one if we'd started earlier and/or had the kids closer together.

If the government is serious about the issue it would need to do the following 4 things (IMHO).

1. Build more houses. We thankfully live in a house big enough where each kid can have their own bedroom but I realise the vast majority of millennials are not so lucky.

2. Make full-time nursery free or almost free for everyone starting from age 1. At one stage where we had two kids in nursery full-time our fees were more than mortgage payments. We're lucky enough to be high income earners, but it would have been extremely difficult to have paid for all 3 at the same time. Ontario has significantly reduced nursery fees, which has benefited my sister.

3. End the two-child benefit cap. So disappointing that Labour is not going to reverse this.

4. Have escalating benefits the more children a family has. I think to make it politically palatable this would probably have to take the form of tax breaks/credits rather than direct payments. Maybe something like lowering the rate of income tax for a set number of years (until kid is 5 years old) with a lower rate for more kids. This way it would not be seen as a handout. I know Hungary is trying something similar, bit not sure what the result has been so far. Also I realise these sort of baby bonus schemes have a bit of fascist overtone to them, which makes me a little uncomfortable even if I think they might work.

And even then, I think most of these will probably have only a marginal impact on birth rates, so immigration is going to have to remain a part of the solution. And I, like I suspect most readers here, am happy with that.