We could make our homes easier to decarbonise by using a crazy, sci-fi technology called a "database"

Change a few words on a contract, change the world

When you think about the hardest sectors to decarbonise, the obvious example is aviation. Because unlike, cars or factories, planes have to stay in the air – which means we can’t easily swap out kerosene for batteries or solar panels, because we need to worry about additional variables like weight and energy density.

However, just because this physics problem is hard, it doesn’t mean that the political or logistical challenges in other sectors can’t be even harder.

For example, take the gas boilers most of us use to heat our homes.

Domestic gas boilers are a big slice of the carbon emissions pie. They are apparently responsible for pumping twice as much CO2 into the atmosphere as all of our actual power stations combined. So if we want to reach Net Zero, we need to replace them with something else.

And what’s annoying is that the solution to carbon-free heating is well known – we’ve already invented electric heat pumps that are amazingly energy efficient and can do the same job as a gas boiler. The problem is not technological – it’s logistical.

You can see the challenge by comparing it with domestic electricity. If you want to decarbonise electricity, it is pretty straightforward from the perspective of the home owner. As a society, we can invisibly change where the electricity comes from. Nothing in your home needs to change1.

But if we want people to stop using gas boilers, that requires a fairly significant reworking of the fabric of your home.

For example, if you switch to a heat pump system, someone will need to come to your house to install it. That means at least a couple of days of awkward cross-class conversations with a tradesperson. And annoyingly, afterwards you’ll be handed a bill that you’ll need to pay for yourself – as unlike a solar farm in a field that feeds existing grid connections, you need to pay to upgrade your own home for yourself.

What makes this a real problem though is that heat-pumps are not cheap. A typical system will cost around £10,0002, and even if you can figure out if you’re eligible for the different government grant schemes, you’re still going to end up paying a number with four figures in it3.

Given all this, it’s probably unsurprising then that the government is seriously lagging on its heat pump installation targets. According to the University of Glasgow, the UK is only installing around 55,000 every year – a long way below its target of 600,000.

I think it’s safe to say, that’s not great.

And to be clear, there are multiple reasons for the lag: The Glasgow report identifies regulatory difficulties, the lack of people to actually install them, the inadequately funding for the various upgrade schemes, and the reality that the perceived value of upgrading fluctuates with the price of electricity and gas.

This is going to take a lot of work by policymakers to fix. But the reason I’m writing about this today is because there is one relatively easy thing the government can do to make the gas boiler transition that little bit easier: We could collect better data.

This brings me to an idea that my friend Anna Powell-Smith has hit upon4. She’s the Director of the Centre for Public Data – and it’s her work that I’m ripping off (or if you want to be more generous, “amplifying”) in this post.

She’s identified a relatively simple contract change which could lead to better targeted subsidies and upgrade schemes for heat pumps. And that’s important, because if we can switch out the very worst boilers first, it means more bang for the buck in terms of climate investments.

And on a more basic level, if we had better data, it would enable us to actually measure our domestic climate progress, when it comes to ripping out gas boilers and replacing them with a technology that isn’t directly killing the planet.

So let’s dig in on exactly what the government needs to do – and read quickly, as if we want to implement this one change easily, there is a significant deadline looming.

Subscribe now (for free!) to get more politics, policy, tech, media and other nerdy stuff direct to your inbox.

Gas certificates and a data gap

Given that the underlying ‘technology’ is literally highly flammable fossil fuels being pumped into your home, gas is unsurprisingly a very highly regulated industry. That means that when you need someone to work out why your boiler is making a weird noise, the work can only be carried out by a registered engineer on the Gas Safety Register5.

This also means that when you have someone carry out work on your boiler, they’ll issue a “Gas Safety Record” – a short document that outlines the work being done, the state of your boiler, and so on. They’re only legally obliged to provide this document to landlords, but typically you’ll get given something to the same effect, whoever you are.

But once the document has been handed to you… That’s basically it. The paper document in your hand is the official record of the state of your boiler.

And this is sort-of weird. It means that even though we have thousands of engineers going into homes and carrying out inspections, it’s still impossible for the government to obtain any high-level data on the state of the nation’s 23 million gas boilers. Because no one is recording all of these data points in one place.

This means that policymakers can’t answer basic questions like “which homes have the most polluting boilers?” or “which landlords are being negligent towards their tenants’ boilers?”.

So Anna’s idea is pretty simple: There should be a central register of gas safety certificates and boiler service reports.

It would mean that when an inspection is carried out, the engineer would upload your boiler’s details and over time, as the register is built up it would enable the government to do some clever stuff.

For example, if we had a central register, it would mean that the government could specifically target households with the oldest, crappiest boilers with incentives to upgrade. Which would be an improvement on the current system, which appears to be “create a largely ineffective upgrade subsidy scheme and don’t tell anyone about it”.

And it would be good for renters too, as it would be possible to identify dodgy landlords with unsafe boilers, and force them to get their shit together.

Making the grade

Now I know what the more paranoid people reading are thinking: “You’re proposing creating a new, big-government database?!”.

And perhaps the slightly less paranoid are thinking “Create a database? That sounds expensive and potentially logistically tricky.”

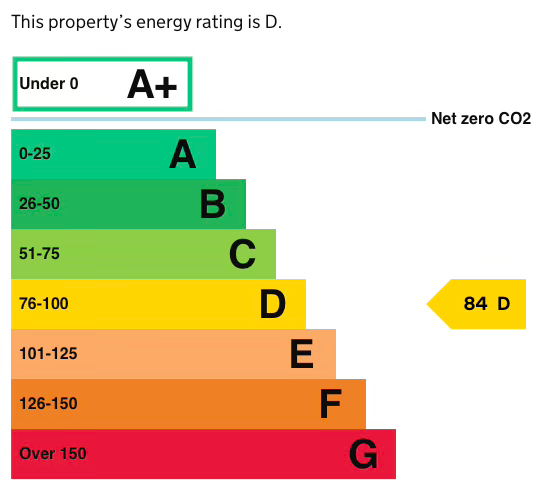

But, as Anna identifies, there are actually precedents for this. For example, there is already an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) register – and it’s already possible to look up any building and view its energy performance. (A bit like the Postcode Address File, this isn’t personal data that would be shared – it’s just information about individual properties.)

For example, here’s the expired certificate for 55 Tufton Street, the notorious home of the climate-sceptic think-tank, the Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF).

True to form, the GWPF’s building has not yet achieved Net Zero, but we can see on the register that it scores a “D” – and that the main heating fuel for the building is natural gas.

10 Downing Street actually scores slightly better – a C grade. But it’s still primarily heated through natural gas. Come on Rishi – lead by example and install some heat pumps! And slap some solar panels on the roof!6

So the ‘ask’ here isn’t that dramatically different from what is already done. If we were to record something as simple as the make and model of the boiler, and maintenance reports in addition to what is already collected, this wouldn’t be going much further.

And in terms of how such a register could be used to turn the screws on rogue landlords, my response is two fold: (a) fuck ‘em, and (b) as Anna points out in her briefing document, this is similar to the other checks that will be part of the new register of private landlords anyway.

Updating the small print

Now here’s the important bit. If we think that creating a register of gas safety certificates is a good idea, then now the time to make it happen.

At the end of March, the current contract for the Gas Safety Register comes to an end. That means that whichever company ends up running it after is going to have to win a new tender from the government.

So right now, there is a golden opportunity to add an extra few lines to the contract to oblige whoever wins to also collect and manage the register of gas safety certificates and boiler inspection reports. This would save the government from building something themselves – and would make it easy to maintain, as it would just be a small part of an already existing contract.

Now then is the time to make it happen. It would be crazy not to do this. And who knows, if we can build a register, maybe there’s a chance that one day we might actually achieve that 600,000 a year target? So let’s do it – and let’s get pumped about better boiler data.

If you think you can make this happen, I’m sure Anna would be delighted to hear from you. And if you enjoyed reading this, then please subscribe (for free!) to get more blazing hot politics, policy, tech, climate and media takes direct to your inbox.

Oh, and follow me on Twitter / Bluesky / etc. You can even LinkedIn with me if you really want to. Or follow me on Instagram for pictures of my cats.

Unless you want to earn bonus virtue points by putting solar panels on your roof.

There are various support schemes but it gets complicated fast, and the gist appears to be that there isn’t much money in any of them, and you’re probably not eligible anyway.

That’s why despite being someone who likes to wag my finger at the government over its climate commitments, until enough of you hit this subscription link, I’m still burning fossils whenever I get a bit chilly.

Anna is, of course, one of the PAF Avengers.

This used to be the voluntary “CORGI” register, but now it is an actual government-accredited thing.

There’s a very easy photo opportunity for Keir Starmer here if he does this when he takes office.

I spent a lot of time working with EPC certificates when I lived in Scotland. The published data is, for lack of a better word, garbage. Huge inconsistency in data entry, IIRC more than 10% of the data is utterly worthless (houses more than 2,500sqm with tiny energy use) it took me weeks to get the 2.5m lines of data clean and, once clean, the only upgrades with a positive investment return on even 2021 electricity prices were lighting upgrades. Which had probably been done.

Know this isn't the main thrust of the article. But, existing government efforts in this space, whether devolved or not, are phenomenally poor.

And the EPC register, at least in Scotland, has data on whether the boiler is condensing or not. If it's not it's an incredibly old one. So, there are good proxies for this data, albeit in very poor quality data...

I thought that when a plumber installed a new boiler they are required to register the installation with the local authority under building regulations, although that is a patchwork of databases and I don't know if the records include anything about the type of boiler installed, like a gas safety certificate does.