Why fixing government tech is a nightmare (but not impossible)

Government is an antipattern

Reminder: Don’t forget my Summer Subscriber drinks, they are happening on Wednesday! If you signed up, you should have the full details in your email!

I’m on holiday for the next few weeks1, so as a very special treat I bring you Odds and Ends of History’s first ever guest post. Dr Liz Lutgendorff is a grizzled veteran of the Government Digital Service (GDS), which I wrote about recently.

Liz spent a decade working to drag the British government out of the digital stone-age – and she has very kindly written this amazing piece that really explains the challenging reality of just how difficult it is to make government digital projects work2.

I’ve become obsessed with something called “antipatterns” – and once you know what they are, you start to see them everywhere.

The term originated in software engineering, but is now used more widely, and it describes when something appears to be a good solution to a problem initially, but ends up having more negative consequences than positive ones.

For example, adding an extra lane to a road sounds like it should reduce congestion – but most urban planners now agree that most of the time it just induces more people to travel, filling up the road once again, creating yet more congestion.

Similarly, when we’ve got a lot of work to do, we might skip sleep to get more done, but inevitably this just makes our brains work more slowly and impacts our health.

Or what about supporting your partner’s Substack career? It sounds like it should make him happier with his work – but all it really means is that he won’t shut up about postcodes.

Where antipatterns mostly manifested in my life though was when I worked in government. That’s because there’s a fundamental disconnect between how the government structures, funds and manages what it does, and how modern technology works.

I spent eleven years at the Government Digital Service, the arm of the Cabinet Office that’s tasked with helping the rest of government modernise and digitise its infrastructure. And what it taught me was that tech proposals that appear elegant and simple on paper often do not survive contact with the messy reality of humans and institutions. And that these institutions create antipatterns that digital services need to defeat.

But luckily, the last twelve years of the government’s digital efforts have not been in vain. In fact, the UK has got a lot to be proud of – but before I tell you why, I need to tell you why making digital government work is so damn hard.

If you enjoy nerdy policy and tech takes, then make sure to subscribe (for free!) to get more of This Sort Of Thing direct to your inbox.

It’s not *technically* difficult

The government’s technology needs aren’t really that complex. Sure there are some exceptions, like the Met Office needing a supercomputer, but the overwhelming majority of public services just need boring things like databases, transaction handling, and a way to provide information on regulations and rights. Data protection and cybersecurity make this slightly more complicated, but fundamentally it isn’t rocket science.

But what makes building these things tricky is an antipattern: The structure of government itself.

For example, take something as simple as putting together a page on the GOV.UK website explaining what to do if your visa application has been turned down. It sounds straightforward but applications could be decided by either the Home Office or the Ministry of Justice, which runs immigration tribunals – two separate government departments.

What we quickly learned when we were writing pages that involved multiple government departments, is that each use different language and have different priorities.

And this makes it hard to write a page containing guidance and advice on what to do, because it takes a lot of negotiation between departments over choices of words and what specific details the page should include3, and so on. There are countless grey areas like this, across the government.

But getting government departments on the same page is just the first step.

Building services

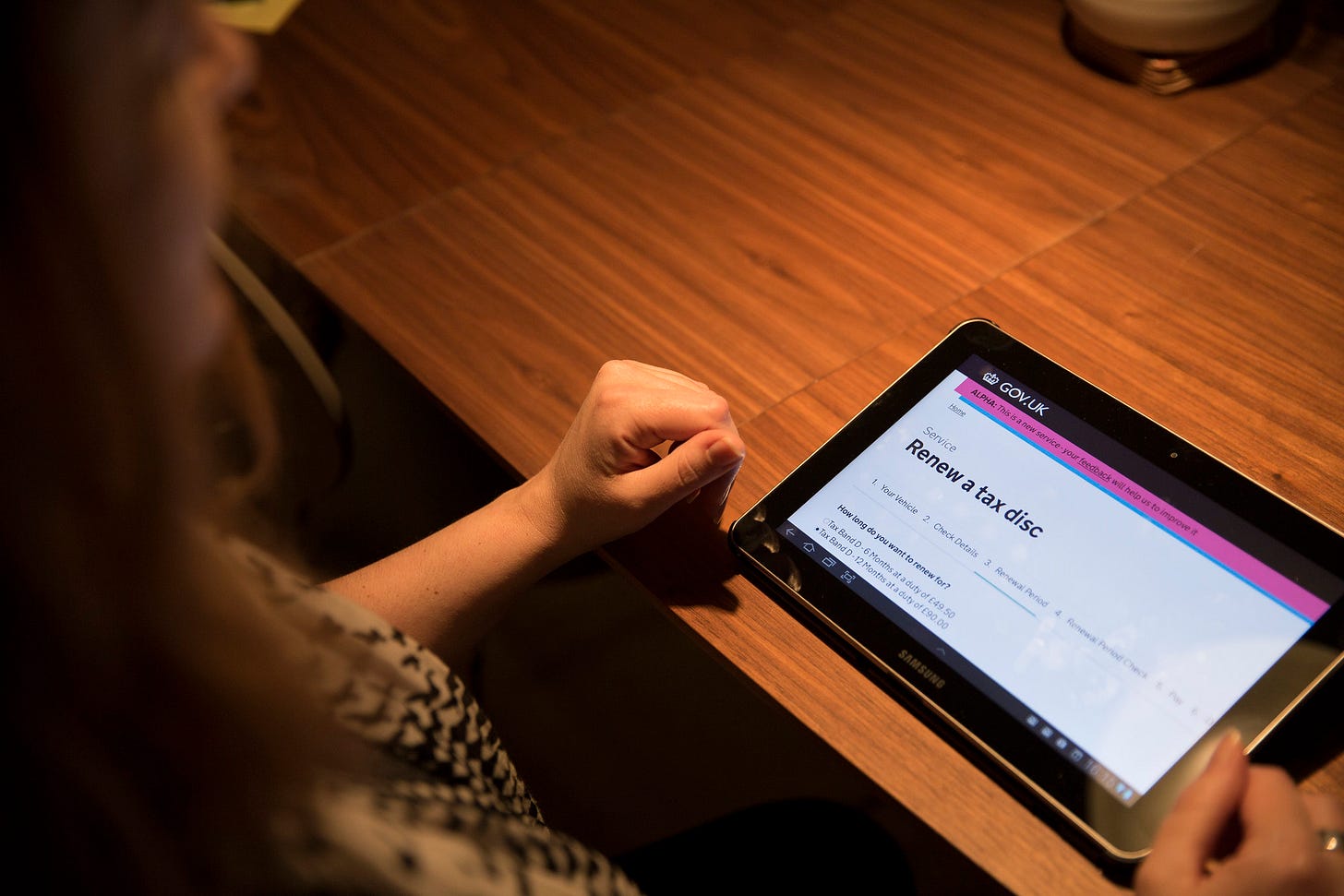

When you want to build not a static page, but an actual digital service, everything becomes more complicated – think services like filing your tax return online or renewing your driving licence, where you may have to login, or there’s a database behind the scenes.

Before you can even start, you need the money to pay for the service, and this means persuading Ministers and the Treasury to give your department some extra cash. So you have to put together a business case to outline the benefits of building such a service.

This is where things can get awkward, especially if all you want to do is upgrade your ageing infrastructure to keep up with technology. What if your business case is essentially: “spend huge amounts of money, hire loads of expensive people with technical skills… to essentially maintain the status quo”?

Sure, you could make the argument as “efficiency, cost savings, blah blah blah”, but ultimately your Minister needs to be convinced that pursuing the project will make them look good. No Minister wants to ask for tonnes of cash and not be able to talk about something new. And they have their own political priorities, which don’t always include “fix some boring tech infrastructure”.

But hey, let’s be optimistic and imagine that you’re lucky, and you manage to get the cash you need to build your service. Then the actual work begins.

And that sometimes starts with unpicking thirty years of previous generations’ technology decisions.

For example, the old system could be owned or operated by an outside contractor, or it could even be that the existing code was written in a long dead programming language like COBOL4.

Anyway, you can’t just hit delete on what existed before, or throw it all away and start again, because the existing infrastructure will have so many things built on top of it.

So before you can even begin, you need to tease apart the existing integrations and carefully examine every aspect of how the existing system works, to reduce the risk of everything falling apart.

Then there’s the challenge that as you build a new service, you need to keep the existing system up and running. Because the government can’t just stop providing their services. We can’t take the driving licence or the benefits payments systems offline for six months while we rebuild them.

That’s why despite various articles (sometimes from former Number 10 advisors) saying that the government should be more like a start-up, in reality that’s basically impossible. The government can’t take risks like start-ups can, because it needs to effectively rebuild the aircraft while it is mid-flight.

People problems

So the challenges are essentially departmental politics, wrangling with the Treasury, and the logistical balancing act of upgrading services, while keeping them up and running. Easy, right?

But what about the people, the civil servants working across government themselves? They’ll make it easier, right?

Perhaps not so much. It’s not that they’re bad – the civil service is populated by people who work hard and care about their work.

But imagine being a civil servant. Your team or department has just been re-structured for the third time in five years. Maybe your department name has changed too. Your job description has no bearing on actual reality.

And the actual work that you do requires constant multitasking. You have your regular and predictable work to do, like quarterly reporting and planning. There’s project-based work you may be called upon to do, like helping develop policies or hold consultations. There’s a never ending stream of emails in your inbox. And then there’s just random, unpredictable things that someone needs right now, for some reason, like answering James’s FOI requests.

In other words, it’s a lot. If you work in the civil service, you’re under pressure every day.

And then along comes me. One of those ‘digital’ people, who is going to help you build a digital service that lets people, say, report the discovery of buried treasure (yes this is a real thing).

I tell you that I just need a bit of your time. But it’s never a ‘bit’ of your time. I need you to be engaged, to participate in the design of the new system, and I need to extract from your brain all of the context that lives in your head and nowhere else to help me do it.

So working together can be surprisingly difficult.

And this isn’t anyone’s fault. Most civil servants want things to improve, as they’d rather not have to use work-arounds and perform pointless acts of data entry that are tell-tale signs of a not-well designed, long out of date digital service5.

However, the reality is that civil servants are also really busy and have got used to doing whatever their job is in their set way. So unless working on a digital project is specifically mandated from the top of government, or is a departmental priority that can be written down as a performance objective, you’re essentially relying on the kindness and spare time of individuals who have a hundred other competing priorities to help you.

Institutional memory

There is one final challenge.

I imagine most people think the government, while a bit fusty and slow, is orderly and has a long, institutional memory. I mean, we’ve been doing this for hundreds of years6.

But what you may not realise is that the government is basically a goldfish. It remembers nothing. It doesn’t know why we made decisions. It doesn’t know that the reason we stopped doing that one thing was because it was a bad decision. Or why no one remembers this and suggests doing the exact same thing a couple of years later.

Or perhaps someone does know why it didn’t work, but that person can’t be bothered fighting against a tide of enthusiasm for the same stupid thing.

Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising. The Cabinet Office has a 25% turnover, so every 4 years there is essentially a whole new department7.

That’s why I spent more time than I care to remember writing the same briefs for about five different ministers8.

So imagine you’ve got through all the hurdles of getting the money from the Treasury. You’ve convinced one (or several) ministers that this digital transformation thing is a good idea, and heck, you’ve even got some buy-in from the civil servants you need to work with in the other department.

…And then because of natural attrition, yet another reshuffle, and maybe a surprise election, you have to do it all over again. But even worse – this time you're behind, because you weren’t able to recruit all the people you needed because there was some mandatory hiring freeze. So your new service can’t do all of the things that you hoped.

Or maybe you were told to deliver it with fewer staff and less budget. So maybe you don’t replace that decrepit piece of underlying infrastructure, and the service doesn’t receive a real upgrade at all.

Fix the government antipattern

This is all to say that digitising government services is hard.

The short, five-year cycles of business cases and budgets are useful constraints, to ensure that a given department can deliver something useful for taxpayers and ministers. But it also leads to a deep bias against real, transformative improvement, as departments know what is and what is not possible in the next five years.

In other words, government itself is the antipattern.

There are however, reasons for optimism. We know that despite this, it is possible to do digital government better – because we’re already doing digital government better in many respects.

For example, the creation of GDS itself was a corrective to the antipattern, as it set standards and defined how the government can build effective digital services.

Similarly, in more recent times, the civil service has started taking technology seriously – the career ladder now treats digital skills as equally important as it does finance and policy. We can see this in the numbers: Forget Google, Facebook and Apple, the Civil Service is now one of the biggest technology employers in the UK.

And unlike a decade ago, senior civil servants are no longer allowed to say “I don’t know anything about computers”.

I’m optimistic that we can continue to fight the antipatterns. In my view, the next challenges are persuading government departments to share data, rather than hoard it – and one day, maybe we’ll solve the difficult problem of digital identity in a country that doesn’t have an ID card system9.

But happily, we are still making things better. There are tangible signs of success. Every time you search for government information, renew your passport or file your tax return online, that’s the result of tenacious civil servants fighting and winning against the antipatterns of government.

Dr Liz Lutgendorff can be found on LinkedIn, Twitter, or in our house.

Make sure to subscribe for more nerdy politics, policy, tech and media takes. Mostly by me, but maybe I’ll persuade Liz to write again.

I’m actually on holiday next week but for complicated scheduling reasons, you’ll get a post from me next week, and a guest post this week, and then again in two weeks time.

They’d use different terms for the process, so Department A would call something a Widget and Department B would call it a Thingamajig. But you’d be told by Department A to go to Department B to ask about the Widget and Department B would say, “sorry, we only do Thingamajigs”.

Editor's Note: When I (James) worked at HMRC almost 20 years ago, if I recall correctly there was one system where we had to use the free notes field to store the ‘real’ information, as the proper form fields were long out of date and couldn’t handle the calculations automatically.

Truly astonishing that instead of George III torching this, we still have a copy of the Declaration of Independence in the Parliamentary Archives.

Yes, stats nerds, this doesn’t quite work, but you know what I mean.

Seriously, look at how many GDS Ministers the Cabinet Office has had since Francis Maude.

The current attempt at solving this problem is called GOV.UK One Login. This is battling one of the strongest antipatterns – the desire for government departments to own every aspect of their services.

The UK government’s digital services are mainly fantastic, so well done to Liz and everyone who made that happen!

Very interesting, Liz! I have been astonished by how functional government websites are right now. When I needed to review my NI contributions history and some other bits recently a chill went down my spine thinking about how I would need to navigate an impenetrable website which would inevitable require yet another login and password, but none of that was true. The government gateway works really well. Good work trumpeting the success! Also, totally agree that doing government is like trying to change the parts of an aircraft that is already in flight.