This new database will fix almost everything annoying about driving

The government is quietly building something excellent

POD! On The Abundance Agenda podcast this week I’m talking about how to make life less miserable for lorry drivers crossing the channel, and Martin explains ‘cow experience’. Plus could London soon become the world’s robotaxi capital? Listen on Apple, Spotify, YouTube or Substack.

There are so many things that annoy me about driving.

I’m a pretty nervous driver, so I hate it when I notice that Google Maps seems to disagree with the last road sign I saw about what the speed limit is. Did I miss something important? Am I going too fast… or too slow?

Similarly, before I set off to an unfamiliar destination, I’ll usually have to spend a few minutes working out the best place to park when I get there. If I’m parking on-street, this inevitably means firing up Google Street View, and trying to spot a signpost explaining the parking restrictions, or whether the street is residents’ parking only.

And then there’s the maddening fact that in the Year of Our Lord 2025, Google Maps is sometimes completely unaware of roadworks on major roads – especially at night. I can think of several times I’ve been caught out by a closed junction, or forced to take a long mystery tour along country roads, desperately hoping to see another yellow “diversion” through the darkness.

I could go on – but I won’t. As this week I bring you something exciting. As it turns out that deep within the Department for Transport (DfT), a new database is quietly being assembled that could fix well… everything. All of the problems I describe above, and so much more – dramatically reducing the number of pain points on English roads.1

It sounds almost too good to be true, but it’s real and it’s very nearly ready. So let’s dig in – and discover how Digital Traffic Regulation Orders are going to stop us raging on England’s roads.

If you like nerdy deep-dives on politics, policy, tech and infrastructure like this, then you’ll like my newsletter. Subscribe for free to get more in your inbox!

The power of TROs

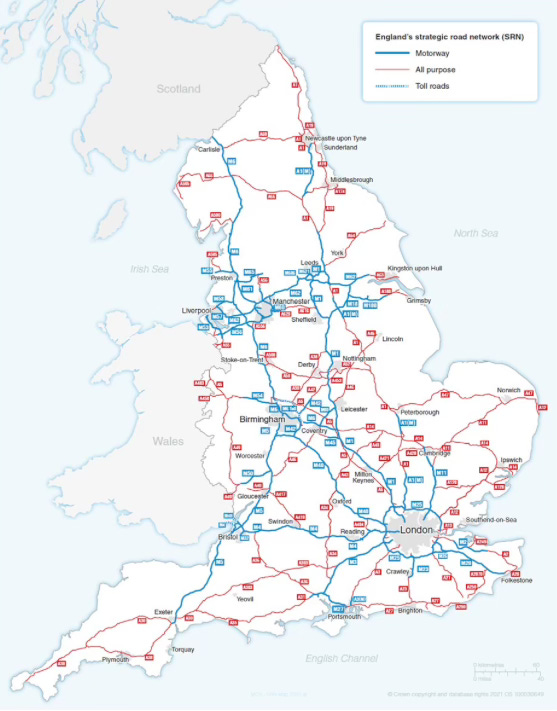

To understand what’s new, you first need to understand how roads are governed – and that is by a plethora of different organisations and agencies.

Your local roads are the responsibility of your local council. ‘Strategic’ roads, like motorways and larger A-roads, are managed by National Highways. In London, many of the most important roads, such as major bus routes, are run by Transport for London.2

Whenever any of these authorities want to change anything on their roads, such as adjust a speed limit, impose restrictions on lorries, designate loading bay, or dig up the road for roadworks, then they are legally obliged to issue a Traffic Regulation Order (TRO).

This is a document that essentially sets out what the change will be, and by law it has to be published in the local press so that, in theory, people can find out about it. In practice however, it’s usually written in near impenetrable legalese, and it’s difficult to work out what is actually happening.3

For example, above is a traffic order that has been issued in Camden to… slightly adjust a red no-stopping route. I think.

Anyway, in addition, though there is no obligation to do so, most traffic orders are also published on the web, on the responsible authority’s website.4

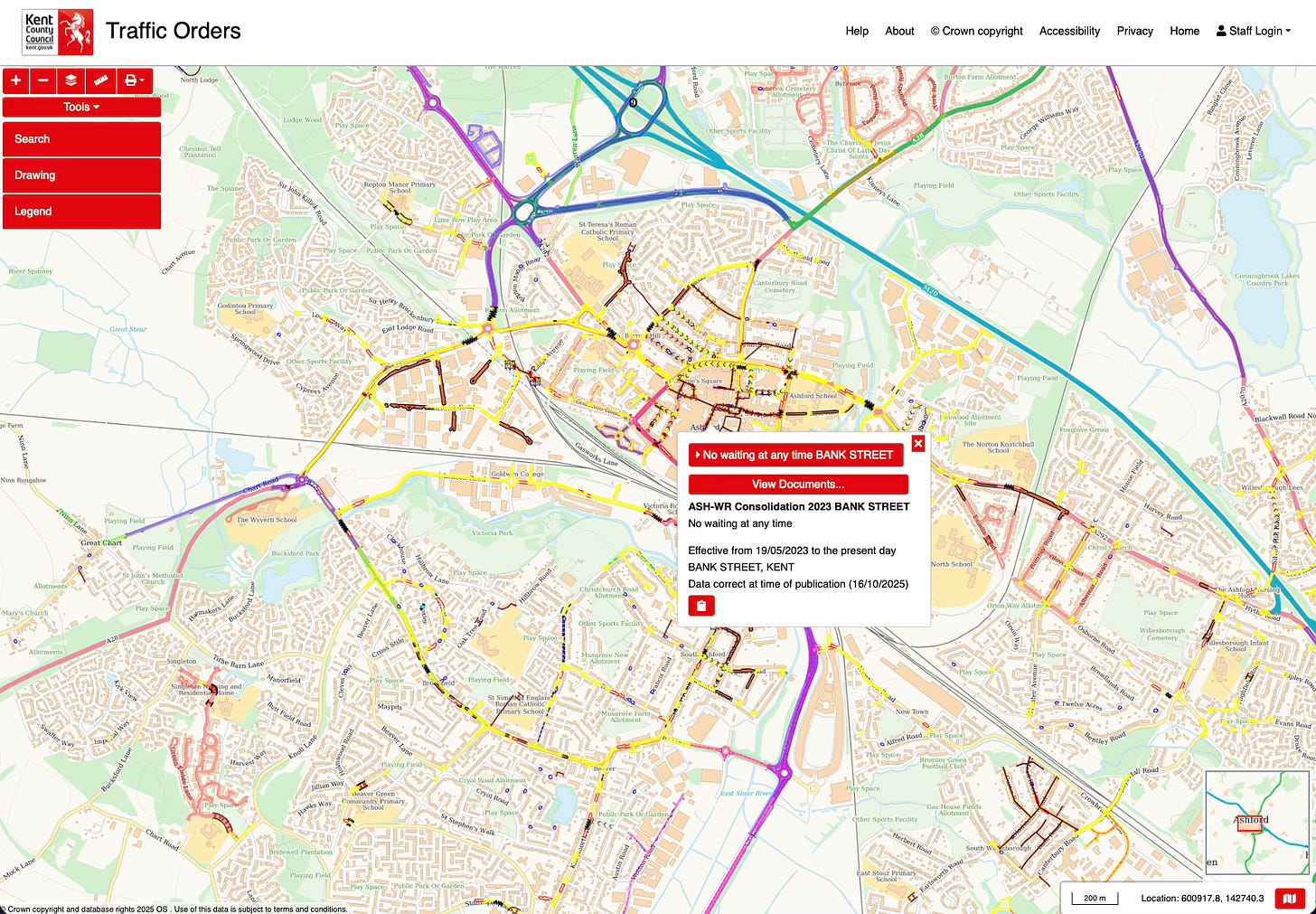

Sometimes these websites have maps that, in theory, should make TROs slightly more comprehensible. But in the case of Kent County Council, for example, all it means is that there is a pin in the map, which links to a document like the one above.

(In fact, maddeningly in Kent’s case, the linked PDFs are clearly scans of TRO documents that have been printed out by one person, and then scanned in again by another.)5

So this is all to say that functionally, TROs are a record of a decision being made, but they are not massively useful. Once they have been published, they basically disappear into the ether.

And this is a huge shame, because in theory TROs contain lots of useful information which could be incredibly useful if it is fed to the right places.

For example, imagine if your Maps app could access all of the TROs – it would know exactly where all of the road closures are across the country, instead of relying on haphazard crowd-sourced reports of roadworks instead.

Or imagine if your satnav knew exactly when a ‘School Street’ or a bus gate was in force, so it could divert you elsewhere at 8:30am, but happily route you through at 11?

And what if your car could be confident that it has up-to-date data on parking restrictions? Perhaps it could warn you if you park up somewhere you might get a ticket?

This sort of information is hidden within TROs that are already being published. All it needs is for someone to take the time to collate all of these traffic orders into one place.

If we can make this happen, suddenly we’ve got a real time, ‘ground truth’ accurate source of the exact rules and regulations governing our roads. Which could make all these use cases, and many more, possible.

Digital Traffic Regulation Orders

So now we know the goal – a single, national digital TRO database.6

To make it actually happen though is much harder. It’s estimated that 53,000 TROs are created every year, and as described above they are distributed across hundreds of authorities. And for this to work, they all need to be wrangled into the same place.

The first problem is basically one of design. There was no set standard on how to store TROs digitally, starting from the most basic questions like how the database should store geographic coordinates, or how it should categorise the different types of restrictions. Then there’s technical questions of how the data should be transported from councils to DfT.

Luckily for DfT this latter question was not as difficult as it could have been. Even though there are hundreds of councils publishing TROs, most use the same case management software to hold their own local TRO database. This means that all DfT needs to do is persuade the software vendor to add an integration, so that when a new TRO is created, it also sends it up to the national database.

However, as I understand it there are still some holdouts, with some local authorities still writing new traffic orders in Microsoft Word, and saving them as PDFs. So to support these dinosaurs, DfT has also built in the ability to upload TROs manually.

So it will likely take some time to get every authority feeding into the new system. The good news though is that the process has already started. A public beta of the digital TRO system was launched at the end of last month, and the first TROs are now dribbling into the new system. And as I understand it, the hope is that all newly created TROs will be automatically fed into the system by some time in the first half of next year.

What’s less clear though is how long it will take to get councils to upload their archives of existing TROs. I imagine uploading an existing database from a case management system would be pretty straightforward. But there could conceivably be TROs created decades ago that are still live but were never digitised. It could be the case that a road was designated a 40mph road in the 1980s and that nothing has changed since.

In any case though, what’s exciting is that the underlying infrastructure is now in place to make digital TROs happen. It will take a while, but over time the database will piece together a complete picture of the rules governing England’s entire road network.

Big implications

I’ve tried to illustrate this piece with some practical examples of how a digital TRO database could be used. But really, one of the best reasons to do this is that we don’t actually know exactly how it will be used.

In that way, it’s similar to the Postcode Address File (PAF). By making the data accessible and open, it will drive the creation of new tools, services and applications.7

But we can make some educated guesses.

For example, relatively quickly we should expect to see navigation apps become a lot smarter, and know a lot more about the roads around us.

And I hope that combined with the National Parking Platform, it will hopefully make finding a parking space less annoying.

But over time, new second-order uses of the data will emerge. Utility companies will better coordinate street works, to avoid digging the same road up twice in quick succession. Fewer parking tickets will be issued erroneously, as the traffic warden’s app could automatically double-check what restrictions are in place. It could make it easier for drivers to appeal parking tickets, as they will be able to check a reliable source of ground-truth.

There’s even talk of how we could have ‘dynamic’ TROs that are applied more smartly. For example, perhaps kerbside parking restrictions could flex to help traffic flow better when it is busy. Or maybe loading bays could become bookable by the hour, to bring order to busy high streets.

And finally, of course, there is the elephant in the room: Self-driving cars.

As things stand, all of the major autonomy platforms use a mixture of mapping and sensor data to drive safely.

For example, Google’s Waymo relies on the company having prepared a detailed 3D scan of the operating area, whereas British company Wayve mostly uses what it can see or sense with on-board cameras and LIDAR sensors. (Tesla’s approach appears to be somewhere in the middle.)

Regardless though, if this TRO data can be made available to self-driving cars it will help them navigate more safely. There will be ground truth of, say, what the legal speed limit is, instead of relying on cameras reading signage. And it will give vehicles visibility beyond their immediate surroundings, as they will be able to tell whether to expect roadworks or a closed street around the next corner.

A quiet revolution

What I love about digital TROs is that if the project of building this new database is successful then it is likely that… no one will notice.

Though there will be behind-the-scenes tools for local authorities to use, there will be no public-facing web presence for motorists. There won’t be a map on GOV.UK where you can click around and browse the TROs around the country. Instead, the system is being designed as an API, that can be plugged into other existing apps and systems.

So what will happen is that Google Maps will become that little bit more reliable, fewer lorries will accidentally wedge themselves beneath low bridges, and autonomous vehicles will experience fewer crashes. It will be incremental gains that we’ll only see in the aggregate, as we shave seconds off journeys and make road users that little bit more productive. But it all matters, for both growth and if we want a functioning country.

And crucially, digital TROs are something that only the government can do. The state is the invisible coordinating layer that works out how to get the data from where it is now – locked inside the vaults of hundreds of highway authorities – to somewhere that it can be useful. DfT has built the system to collect it, and as soon as the Transport Secretary says the word, there will be a legal mandate for local authorities to feed into the system and the filling of the database will begin.8

And perhaps one day in the future, if we’re lucky, we’ll forget why driving ever annoyed us.

If you like nerdy posts about politics, policy, tech and infrastructure, you’ll like my newsletter. Subscribe (for free!) to get more of this direct to your inbox.

Transport is devolved, so Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have their own systems. Though I believe they are being offered use of the software being built for England.

This is pretty inconsistent. Until last month when TfL took over, Oxford Street – one of the most important roads in the capital – was owned by Westminster council, who spent many years resisting pedestrianisation.

In 2025, this is essentially just a de-facto subsidy for some of the worst local news websites on the planet.

There’s not actually a law requiring web publication, because the law was written before the internet was a thing.

How did Reform-controlled Kent County Council’s local version of DOGE miss this one?

From a legal perspective, the TROs produced by local authorities will remain the official legal document for whatever is being done, but this is a database that will capture all of the useful information.

Though unlike the PAF it will be mostly open data (there’s a nuance to it that I’m saving for a future post).

A Statutory Instrument was created in the 2024 Autonomous Vehicles Act, and the plan is to activate it once the beta is over.

Hi James - really interesting!

On self-driving cars, British (and European) roads would seem to present challenges perhaps not present in the American cities where they have taken off: tricky roundabouts, winding country lanes, narrow (sometimes cobbled) lanes, and in certain cities like Cambridge, cyclists and pedestrians that seem to come from nowhere. Or perhaps these differences and challenges are overstated? Anyway, I'd love to read something on how self-driving car companies are planning to deal with some of the peculiarities of British / European roads!

I hope the licensing of this is compatible with OpenStreetmap as well as the commercial satnav businesses.