How the government's new digital ID will work

And why I've changed my mind on ID cards

It’s finally happened! After literally years of debate and months of speculation, it appears the British government is finally building a digital ID system.1

Due to be announced later today by the Prime Minister, the plan is that digital ID will help the government crack down on illegal working and illegal immigration, and if you’re a regular reader of my newsletter, it all might sound a little familiar.2

That’s because the plan appears to be more-or-less a wholesale copy and paste from the infamous ‘Britcard’ paper published by the Starmerite think-tank Labour Together back in June. At the time, I wrote about how their proposal would work – and why it has persuaded me that, on balance, digital ID is a good idea.

Anyway, given the proposal has been taken up by the government, and digital ID has become a live political debate – I thought I’d share once more my explainer on how the system works – and the thinking behind it.

So here’s everything you need to know about the plan – including the technical stuff, why most of the building blocks for such a system are already in place, and why I ultimately think it’s a good idea.

I can only write about nerdy ideas like this every week with your support, so please subscribe now (for free) to get more like this direct to your inbox.

We also spoke to Kirsty Innes, one of the authors of the paper, on the June 16th episode of The Abundance Agenda – which is well worth a listen to here. (Or on Apple, Spotify or YouTube!)

Rights and wrongs

The argument at the heart of the Labour Together paper, which was written by Kirsty Innes, Morgan Wild and Laurel Boxall, is that the government should build a digital identity system to carry out the “right to work” checks that happen when you get a job, and the “right to rent” checks that happen when you rent a home.

These are legal burdens put on employers and landlords, to make sure that you have, well, the legal right to work or rent. And at the moment, the system for doing so is pretty messy.

If you’re a British citizen, it’s relatively straightforward for most people. You can just show them your passport – but not everyone has a passport. So you might have to use your birth certificate instead. Good luck digging that out of the back of your parents’ cupboard.

However, if you’re not British, proving your rights can be significantly more annoying. If you’re lucky, depending on the type of visa you’re on (or if you’re a settled EU citizen), you might be able to get a share-code from the GOV.UK website, which your employer or landlord can use to check your status. That’s relatively painless.

But if you’re unlucky, you might have to dig through reams of immigration paperwork, and use that as compiled evidence, and it is exactly as annoying as you imagine.

And these checks are not just frustrating for workers and renters, they’re a pain for employers and landlords too, and checks are often outsourced to third-party companies, adding more layers of bureaucracy.

So what the authors of the paper are instead proposing is that we replace these bureaucratic hurdles with what they call “BritCard” – a digital ID that is held in an app on your phone. Instead of needing to provide your new employer with a big pile of papers, you would instead simply display a QR code3 from your BritCard app, and your employer could scan it with a verifier app, which would give the green light for you to get to work.

And here’s the clever part about the Labour Together plan: Much of the technical infrastructure to actually build such a system already exists. We just need to use it for this new purpose.

The One Login foundation

I’ve written about One Login before. This is a common login system that will one day be used across nearly all of the government’s digital services – the websites you use to pay your taxes, claim benefits, update your driving licence, and so on.

As things stand, the system is still in the middle of a slow roll-out: It’s currently the login system in use for a bunch of niche government interactions like applying for an import licence or getting a fishing permit in Wales. But eventually (just don’t ask exactly when), the plan is for all of the really big government services to move over to One Login too – things like HMRC’s self-assessment tax return service, and the DWP’s Universal Credit system.

So it will (eventually) mean that you’ll only need to remember one username and password for almost all of your interactions with government – and your One Login will become more useful the more government services you interact with.

And crucially from a digital ID perspective, One Login already has a clever identity proofing system built into it. It’s slightly more complicated than this, but in principle it is designed so that, for example, once you’ve already proven who you are to, say, DWP when claiming benefits, you won’t have to provide the same credentials to DVLA when you register your car.4

Perhaps you can see why this system would make the perfect foundation of a broader identity system: Once One Login is in use across government, it will create a massive database containing literally tens of millions of verified people.

However, this isn’t the only component you need for an identity system. What about the “right to work” app that would be needed? What about the place where we can store and access our “BritCard” credential, should we need to present it?

It turns out this already exists too.

Enter the wallet

Back in June, the government launched the official GOV.UK app, with the intention that it will be the new centre of our digital interactions with government – a bit like how all of our healthcare interactions are being slowly piled into the NHS app.

One Login will (again, eventually)5 be an integral part of how the app works. The idea is that it will eventually evolve into what looks like – to the end user – basically Facebook but for your government interactions, where inside the app you can do whatever you need to, whether pay taxes, register a business or tax your car.

And though the feature hasn’t yet been added, eventually the GOV.UK app will also contain a major feature called “GOV.UK Wallet”.

Functionally, this will work very similarly to the Wallet apps made by Apple and Google, which are digital repositories for your bank cards, loyalty cards and tickets. You know, like a real wallet.

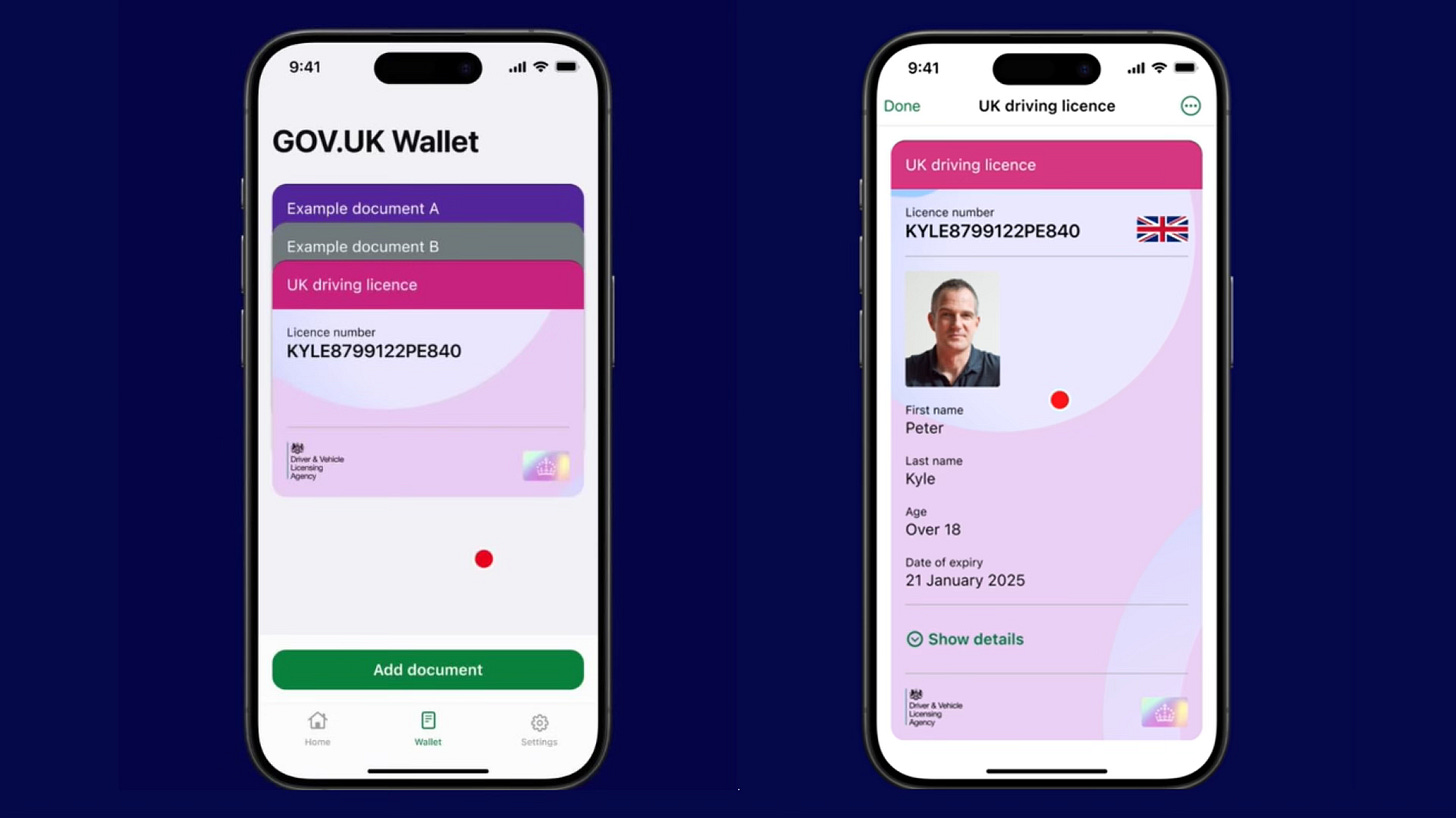

Here’s what the GOV.UK wallet will look like:

The GOV.UK Wallet will do something similar to Apple and Google – but will be a place for storing government-issued credentials – which are a key conceptual building block in the government’s ambitious digital plans.

The idea is best described by digital government’s spiritual leader, Richard Pope, in his excellent book Platformland. “Credentials” – or what tech people might call “Tokens” – provide “digital proof that someone has done something.”

For example, when you pass your driving test, you receive a driving licence – a credential showing that you are entitled to drive. Later this year, you’ll be able to store a digital version of your driving licence in your GOV.UK Wallet – and it will carry the same legal weight as your physical card.

But the reason the government is creating an entire Wallet is because, when you think about it, the public sector issues tonnes of credentials like this.

For example, instead of needing a physical letter from a doctor to prove to DWP that you’re entitled to certain sickness benefits, (eventually) your doctor may be able to issue you with a digital credential that will prove you’re entitled, without you needing to reveal any personal medical information to DWP.

Or perhaps the wallet could hold a credential proving that your child is entitled to free school meals, or that you hold a blue disability badge.

And this is where BritCard slots in. Thanks to GOV.UK Wallet, BritCard wouldn’t need to be a whole new system – it could just be another credential stored in your wallet, and it could prove your right to work, right to rent, and act as a verified ID card more generally, for other situations when you may need to prove that you are who you say you are.

So I think Labour Together’s logic makes a lot of sense. The underlying systems to make BritCard possible – save for the specific links with specific visa and passport databases – have already been built. One Login and Wallet take us most of the way to a system of digital ID as it is.

Do we really need this?

Since the paper was first published in June, it has definitely proven controversial in the extremely niche community of people who care about digital government.

For example, my postcode campaigning pal, Peter Wells, took issue with Labour Together’s claim that BritCard could possibly have a “canonical up-to-date view of the set of people with the right to be in the country”. And Richard Pope, who I mention above, says there are “lots of sensible things” in the paper, but is nervous about how it flattens the concept of digital credentials into a singular ‘card’ metaphor.

And then there is the simple civil liberties point that, well, should the right to work and right to rent checks be carried out in the first place? Both are actually fairly new ideas – the former introduced in 1997, and the latter in 2016.

So why is now the moment where I have apparently taken the Blairpill on digital identity cards?

I think my view comes down to a couple of factors. First, these checks are not going to go away.

For as much as we may wish to have a philosophical debate about the surveillance state, and as uneasy as theses sorts of checks may make me in the abstract, the reality is that in the medium-term, it would obviously be politically impossible to remove them. It wouldn’t just be the Daily Mail kicking off – the only words we’d hear from the right until the next election are “Labour is soft on illegal migration”, and they’d have some credible evidence.

So given this reality, we may as well make these sort of checks easier to carry out. As the status quo isn’t that these checks aren’t happening – it’s that they are happening, and they are a nightmare.

I’m also sympathetic to the argument made by the authors in the paper that turns the “papers, please” criticism on its head – they argue (as does the political scientist Rob Ford) that having a digital credential proving your rights could protect you from the state, with the obvious example of this being the Windrush scandal, where dozens of long-term, legal British residents were wrongly deported because of a lack of paperwork.

As co-author Kirsty Innes told me on The Abundance Agenda podcast back in June – the problem with the “What about Farage?” argument is that if a future oppressive regime does come to power… well, there’s nothing to stop it from building an ID card system and abusing it if they wanted to – so it’s better to build a version now that has legal checks and balances around when it is used, and so that it is designed on a technical level, per the ideas of Richard Pope’s Platformland to give people better control over how their data is used.6

And she also makes a persuasive case against the Farage argument: that the way to persuade people that populist authoritarians are not the answer is to actually make government more functional, and work more effectively. Which is something that digital ID can help with.

So on balance, I’m inclined to take the pro-digital ID side of the trade-off. BritCard is a good idea – but we should always remain vigilant of the trade-off.

Subscribe (for free!) to get more of politics, policy, tech, infrastructure and media direct to your inbox!

And don’t forget to listen to the June 16th episode of The Abundance Agenda, where we spoke to Labour Together’s Kirsty Innes about, well, digital ID and the BritCard proposal! Listen on Spotify, Apple or Substack.

Oh, and if you’ve read this far you’ll definitely like this one I wrote too.

I guess I’ll have to update this piece on the government’s other identity credentials system. Though in my defence, the headline was absolutely correct at the time.

There’s also been chatter in Westminster that Starmer may also use the speech to more forcefully tell the racists to fuck off. I’m not sure if it will happen, but if it does it will be a nice confluence of O’Malley-relevant ideas. Maybe he’ll also commit to liberating the PAF to make it three out of three?

Or use NFC, of some other mechanism of transferring data.

One day I’ll write an ultra-nerdy post about how One Login works behind the scenes, as it is designed in a super clever way, with different levels of confidence for different activities and different types of document.

The beta version of the app is little more than a directory of links to pages on GOV.UK.

One commonly cited example of this is Estonia’s “X-Road” system, which lets citizens view a log book of whenever different government departments and agencies have looked at or forwarded their data.

Really good piece, you've swayed me from a 'bad idea definitely' to 'maybe it would help actually'. The governments passport service is now incredibly good, it would make a material change to people lives if they made other services as accessable.

The other major question I have is why is labour coms so bad that the best piece arguing for these id cards is here ? Blowback from the introduction of these cards is already substantial.

I'm in favour, but I don't like the name much. It'll go down really well in Derry